TAMIL SEPARATISM AND THE INDEPENDENCE MOVEMENT

KAMALIKA PIERIS

June 23rd, 2018

Tamil separatism” is not a post-Independence phenomenon, as we are made to believe. Tamil separatism had emerged long before ‘Sinhala only’ (1956) and ‘standardization’ (1970) took place. Tamil separatism started in the 1920s when Sri Lanka was still under the British. Tamil separatism was a dominant political force in south India at that time. The Justice Party, which wanted Tamil rule, was in power in the Madras Presidency of India from 1920 onwards. This would have given strength to Tamil separatism in Ceylon.

Sandagomi Coperahewa records that the term Tamil Eelam” was used for the first time for the North- East by Ponnambalam Arunachalam in his address to the Tamil League in 1923. In this speech he spoke of the ‘desire to preserve our individuality as a people,’ (Coperahewa 2009 p 59)

When it became clear that Ceylon was moving towards independence and that the British were leaving, the Tamil leaders became alarmed. The ‘Ceylon Tamil’ and the ‘Ceylon Moor’ knew that they owed their position to British rule in Ceylon. They were concerned about what would happen to them in independent Ceylon. They opposed all moves towards independence. They protested before the Donoughmore Commission, (1927) the Soulbury Commission (1944) and strongly objected to the” Ministers Draft Constitution” (1944).

The 1920’s saw the beginning of Ceylon’s agitation for independence from Britain. To start with, the Ceylon National Congress wanted territorial representation in the Legislative Council elections planned for 1924. The Tamil leaders were against this. A memorandum prepared by Ponnambalam Ramanathan was sent to the Colonial Office in London in 1922. This memorandum set out the view of the minorities on future constitutional reform and included a draft scheme of constituencies with representation on an ethnic basis. Governor Manning endorsed it and praised it as a model memorandum.

But in London, the Colonial Office authorities, Viscount Milner and H. Cowell ‘were perceptive enough to raise doubts about the Tamil demands’. ‘Their demands in the joint memorandum are excessive; it would be a doubtful measure to agree to communal representation of Tamils who are a progressive and numerous class,’ they said.

‘All Ceylon Village Committee Association’ was formed in 1924, but the Northern Province had its own association the ‘North Ceylon Village committee.’ This organization lobbied the colonial government about colonization schemes, provision for irrigation and causeways, credit for tobacco and paddy farmers and solicited aid for village workers.

Recognizing Ceylon’s desire for greater independence, Britain appointed the Donoughmore Commission in 1927 to look into a new constitution for Ceylon. Alarmed Tamil leaders appeared before this Commission and lobbied for communal (ethnic) representation. Donoughmore Commission did not accept their views.

The new Donoughmore Constitution which came into effect in 1931 provided, instead for a State Council, with Executive Committees for each subject. It also gave a vote to all citizens. The Tamil leaders heartily disliked this universal franchise vote. They count people like cattle, 20 to that side and 30 to this side. There is no way that the village headman and the labourer are going to have the same vote!” said Ponnambalam Ramanathan in 1931.

H.A.P. Sandrasagara made a significant observation in 1931. He said in 1931,’ I will make Jaffna an Ulster and I will be its Lord Carson’. This remark is revealing. Let us therefore looked at what happened in Ulster.

‘Ulster’ was the Protestant part of Northern Ireland, with Belfast as its center. In 1912, Britain planned to give ‘Home Rule’ to Ireland. Ireland was a part of Britain at the time. Instead of rejoicing, ‘Ulster’ objected, because under Home Rule, Protestant Ulster would become a minority in deeply Catholic Ireland. Unionist Ulster wanted the link with the British Empire to continue.

On ‘Ulster Day’ 28 September 1912 over five hundred thousand Unionists signed the Ulster Covenant drawn up by Irish Unionist leader Sir Edward Carson, pledging to defy Home Rule by all means possible. They prepared for war. They obtained weapons from abroad. Carson meanwhile lobbied Parliament. Parliament agreed to give partial autonomy to Ulster inside the Home Rule. The legislation was ready, but World War I intervened. Thereafter, Government of Ireland Act 1920 partitioned Ireland, creating Northern Ireland and setting up separate Home Rule Parliaments in Dublin and in Northern Ireland.

The matter did not end there. Northern Ireland erupted into a protracted, highly publicized Protestant –Catholic war which lasted from 1968-1998. There was severe rioting between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland. This Northern Ireland conflict has been described as a thirty year bout of political violence, low intensity armed conflict and political deadlock. It included an armed insurgency. During Unionist rule, Catholics were discriminated against and Irish language and Irish history were not taught in state schools. The conflict ended with the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 which recognized both Protestant and Catholics in Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland’s future remains uncertain.

Now, back to British Ceylon. Governor Caldecott, in 1938 recommended the abolition of the State Council and replacement with the Westminster system of Cabinet government. G.G. Ponnambalam, leader of the All Ceylon Tamil Congress, and member of the State Council wrote to Governor Caldecott in 1939, saying that there were strong differences of opinion between the majority community and the minorities regarding the next constitutional change. He said that any action on the part of the British to support the ideas put forward by the Sinhalese Ministers in the State Council, would be viewed with extreme disfavor by the Tamils. He said he was writing this letter at the instance of a number of representatives of the minority communities.

A set of State Council members consisting of 2 Tamils (Ponnambalam, Dharmaratnam) 2 Indian Tamils (Natesa, Pereira) one Muslim (Kaleel) one Malay (Jayah) had also sent a telegram to Britain asking that any future constitutional reform should safeguard minority representation in the government.

In November 1939, G.G. Ponnambalam wrote to Sir N. Stewart Sandeman, Conservative MP from Lancashire, telling him that ‘there are certain sinister moves by being made by our Sinhalese friends just now to wrest control of the country.’ Sandeman forwarded the letter to Colonial Office, stating” I am taking almost as much interest in Ceylon as I did on the question of the India Bill. My sole aim in doing so is my feeling that the minorities have to be protected more in the East even than in Europe. I have the feeling that the Sinhalese may try to exploit the fact that there is a war on (he is referring to the Second World War) in order to gain their own ends.” This shows that the Tamil Separatist Movement had started cultivating friends in UK, long before Eelam.

In 1941, Sir Mohammed Macan Markar, as leader of the Muslim minority met Governor Caldecott. He argued that if the Executive Committee system was to be abolished, then some method of ‘protecting minorities’ be devised in its place

In 1942, Britain promised to give greater self -government to Ceylon once the Second World War came to an end. Britain asked the State Council of Ceylon to prepare a draft constitution for Ceylon. The Board of Ministers of the State Council, led by D.S. Senanayake, sat down and drafted a constitution and sent it off to London. This was known as the ‘Ministers Draft Constitution ‘of 1944.

This Draft Constitution was based on the Westminster model. It included weighted representation for Tamil majority areas. In addition to the normal allocation of parliamentary seats on the basis of population, the Northern and Eastern Provinces would be allocated an additional number of seats to increase their representation, because these two provinces were sparsely populated. There would also be a clause which would prohibit discriminatory legislation against minorities.

The Tamil leaders were not impressed. They informed London that they did not like the draft, specially the way it had been prepared. The “Draft ‘ had not been submitted to the State Council for approval. Tamil leaders had serious ‘anxieties over the protection of their legitimate rights’ in the future constitution.

Britain decided to appoint a committee to look into the matter. The ‘minorities’ of Sri Lanka had reservations about this also. ‘Representatives of the minority Communities in State Council” had requested Ponnambalam to write to Secretary of State, in London, and inform him that they were against any Commission appointed only to consider the ‘Draft Constitution’ which had been drawn up by Ministers who belonged only to -the Sinhalese community. Ponnambalam had been asked to point out that that the minorities constituted at least one quarter of the House, and thus claimed the right to contribute to the discussion. Secretary of State, in London had replied that the draft constitution would not be accepted until it was thoroughly examined.

Ponnambalam objected to the appointment of a Commission only to examine the draft Constitution’ of 1944. Ponnambalam called for a commission to review the situation in Ceylon, saying that the existing constitution, which also had operated to the detriment of the minorities, should be amended.

Ponnambalam kept on writing to the British government about Tamil views and Tamil objections to the constitutional reform process. He sent a spate of communications to Britain, complaining and criticizing. Ponnambalam was the chief, in fact, the only, personality of any significance in the arena at this time on this matter observed K. M de Silva.

Thanks to these letters, London wanted Ponnambalam’s All Ceylon Tamil Congress investigated. Colonial Office prepared a note on the ACTC which said that the Tamil Congress was a recent organization. It was neither representative of the Tamil community nor did it have deep roots in the Tamil community. It was an artificial creation of a group of Tamil politicians led by Mr. Ponnambalam, for the purpose of presenting a unified front against the Sinhalese majority community where constitutional reform was concerned.

The Tamil assumption that the Sinhalese and Tamil communities cannot work together in politics was ‘not borne out by events’, continued the note. Colonial Office decided simply to acknowledge the various communications from Ponnambalam and state that they have been referred to the Secretary of State for the Colonies.

K.M de Silva has suggested that these protests were effective, and contributed to Britain’s decision to widen the terms of reference of the Soulbury Commission, to include a study of the minority situation. However, G.G. Ponnambalam did not impress the two Ceylon Governors he dealt with. Caldecott, Governor of Ceylon from 1937-1944, treated his letters rather coldly. Caldecott questioned one of Ponnambalam’s statements in his letter of 4.4.1944, sought clarification, and said that he did not think the matter important enough to send it by telegram, as Ponnambalam had requested. Air mail would do. However Caldecott refers to Ponnambalam as ‘redoubtable and intransigent’,

IN 1944, a Tamil doctor from South Arcot in southern India, Dr. S Ponniah wrote to the Colonial Office in Britain, emphasizing the difference between ‘Tamil Ceylon and the rest of Ceylon”. Here are quotations from his letter:

With reference to the future political reforms to be granted to Ceylon, I beg to state [that the Tamil speaking part of Ceylon (re: comparison of other minor communities with the Tamils) is a well defined territory where Tamil only is spoken. Besides, it had its own history, civilization, politics, and Kingdom for roughly about 1,500 years 1 or perhaps more. It had been and is different from the rest of all Ceylon by history, race, language, creed, culture, customs and manners, politics, civilization and the ideals of life.

Tamil Ceylon is a unit by itself. If Tamil Ceylon with Jaffna as centre is created a separate political unit by the World Protecting British Nation, the story will be different. Jaffna will play the part of a bond of union between Mother India and Daughter Lanka (Ceylon) and of a buffer political unit medium between these two countries for the happy betterment of their mutual feelings and their economic, political, and cultural progress. The best of understanding has still to be reached between these two countries and it is essential and vital that it should be reached soon as attested by war time troubles.

Some politicians will try to plaster over the differences between Tamil Ceylon and the rest of Ceylon but it is extremely difficult to make the two ends meet. The promises of these politicians are with selfish motives, short-lived and Ideologic. They are ambitious and power-loving; they want to satisfy their feelings of supremacy and to bring all Ceylon under one umbrella. If the ideas and ideals of these politicians are carried through, the Tamil people of Ceylon will be reduced to the position of ryots and serfs. Almost all the coveted high posts will be occupied by the major community as was the beginning [sic] seen during the past decade or two. All the public money will be spent to better their own lands and people. The Tamils will suffer economically and they will deteriorate and degenerate mentally and morally. The Tamil language and culture will slowly disappear, the beginning of which is seen in the Ceylon University. Whereas in India they are Tamilising sciences and are ‘beginning to teach Mathematics and Sciences in Tamil in the schools and colleges. Incidentally I may add a Jaffna University has to come into being sooner or later. » (CO/54/986/7 no 35 of 1.Sept 1944, British Documents on the End of Empire Item 223.)

In 1944, the British government in London appointed a committee led by Viscount Soulbury to go to Ceylon, study the situation, and recommend a suitable constitution for Ceylon (Sri Lanka). They were specifically asked to discuss the matter with the ‘minorities’. This Commission arrived in Ceylon in 1944. The Commissioners looked around, met the State Councilors and the leaders of the ‘minorities’ and made its recommendations in a report titled Ceylon, Report of the Commission on Constitutional reform” published in 1945.

The Tamil leaders had a series of complains to make to the Soulbury Commission regarding State Council. The Commissioners looked into each of the complaints and recorded their observations in the Report. The Tamils complained about discrimination in appointments to the public services. They stated that before 1931, arithmetic was compulsory for the General Clerical services examination. After the State Council was established in 1932, arithmetic was deleted. This was done because the Tamils were superior at mathematics. The Soulbury Commission did not agree. They found, instead that the Burghers and Tamil were over represented in the public service. The Sinhala challenge to the Tamil position was not ‘discrimination.’ It is the ‘natural effect of the spread of education and efforts made to bring other portions of the island up to the intellectual level of one portion of it.’

The Tamils also complained of discrimination in the provision of schools. They complained that very few of these government schools were sited in the north and east. The Commissioners thought otherwise. The Soulbury Commission rejected the statistics offered by the Tamil groups, saying that they differed greatly from the official statistics. They pointed out that Jaffna already had a fine network of schools, provided by the Christian missions. The Soulbury Commission concluded that the discrepancies in expenditure were due to the government’s desire to ‘redeem certain localities and communities from the neglect of past years’. The Commission praised Kannangara, ‘himself a Sinhalese and Buddhist ‘for promoting schools for Muslims.

The Soulbury Commission was full of praise for the good work done in education by the State Council from 1931. They said that the Minister for education, C.W.W.Kannangara was attempting to provide government schools throughout the country. Between 1931 and 1944 there had been a remarkable expansion in the provision of Sinhala and Tamil schools. Since there was not enough money for school buildings, Buddhist temples had been asked to allow schools to be conducted in their halls. Soulbury Commission noted that Kannangara had succeeded, against fierce opposition to introduce a system of school meals for children. They also noted that Kannangara wished to introduce English to all schools and develop a set of Central schools

The Tamils complained about the lack of agricultural and irrigation development in the northern and eastern provinces. They charged that after the State Council was set up, the money allocated to the north and east had decreased. Soulbury Commission pointed out that the British had concentrated mainly on restoring irrigation tanks in the north and east. Up to 1931, nearly 50% of the total expenditure on irrigation works was for the northern and eastern provinces. The State Council had concentrated on developing irrigation in the Central and North Central provinces. Soulbury Commission also noted that the population in the north and east was little more than 10% of the total population. But from 1931 to 1943 the expenditure for the north and east was around 19% of the total allocation.

The Tamil complained about the Anuradhapura Preservation Ordinance, 1942. This Ordinance was enacted to preserve the historical city of Anuradhapura and create a new town outside the zone of its archaeological remains. The Tamils complained that there were around 10,000 Tamils and Muslims in Anuradhapura , and they either owned or occupied a greater proportion of the land affected by this Ordinance. Hennayake (2009) confirms that Anuradhapura town had ‘always had’ a relatively large Tamil population. They were largely engaged in business and related activities. Soulbury Commission thought that the preservation of the ancient city of Anuradhapura was in the best interest of Ceylon as a whole. It was sensible to safeguard the remains of an ancient city of great extent and beauty. They did not think this specially benefited the Sinhalese and saw no intention to discriminate against the minorities

The Tamil and Muslim traders had objected to the all island Cooperative movement which the State Council had started. The All Ceylon Tamil Congress stated that the Cooperative sector was intended by the Sinhalese to cut out the trade of the Indians and Europeans. They said the Indians had an aptitude for trade which the Sinhalese did not possess and the government wanted to benefit the Sinhalese at the expense of the others. Soulbury Commission declared that it was a good thing to develop a cooperative movement as it would benefit the poor. The cooperatives they visited were well run. The charge of communal discrimination was dismissed.

The Tamil leaders also complained about religious favoritism. The Tamil leaders had stated that there were just 61% Buddhists in 1944 with 22% Hindus and 10% Christians. They had combined the Ceylon and Indian Tamils together. They complained against the Buddhist Temporalities Ordinance of 1931. Under the terms of this Ordinance the Public Trustee was expected to carry out the administration of the Buddhist temples. The Ceylon Tamils had complained that by this nearly half a million rupees from 1931 to 1944, went from the public revenue, year after year as the cost of the Public Trustees administration. This meant that the taxpayer was paying for the administration of temples which served only a section of the population. The minorities considered this to be discrimination in favor of Buddhism . Soulbury Commission agreed with this, and concluded that the Sinhala majority of the State Council had favored their own religion.

In 1945, the Soulbury Commission produced the Soulbury Report, recommending further constitutional reform for Ceylon. The Report recommended a Prime Minister, Cabinet, and a Legislative Assembly. Its recommendations resembled the ‘Draft Constitution’ of the State Council. D.S. Senanayake, later Ceylon’s first Prime Minister, wanted to go to London, to meet the British Secretary of State to press for independence, before this Report was released . He was invited in his capacity as Vice-Chairman of the Board of Ministers and Leader of the House. He was in London in August and September, 1945.

G.G. Ponnambalam also requested the same privilege. He sent a telegram, through the Governor, stating that the All Ceylon Tamil Congress did not like the exclusive opportunity given to D.S.Senanayake to hold discussions with the Secretary of State without any representative from the opposition. Senanayake cannot claim to speak for ‘ five out of the six communities in the Island.’ Tamils wanted an equal opportunity of discussion with Secretary of State. Secretary of State replied that he was not prepared to issue invitations to Ponnambalam or anybody else, nor was he going to pay for their passage to come to London. It was also decided that Secretary of State should not discuss the Soulbury Report with Ponnambalam.

Monck Mason Moore who was Governor in Ceylon (1944-1948) had to deal with Ponnambalam’s visit to London. He remarked that that he did not think that Ponnambalam had the wide backing he claimed. He recommended that the Secretary of State should not issue an invitation to Ponnambalam to come to London, as no good purpose would be served by such an arrangement. He also stated that Ponnambalam was not prepared to accept the explanation that British was inviting D.S. Senanayake to London only as Leader of the House, despite the fact that Moore had had two interviews with Ponnambalam.

Ponnambalam went anyway, accompanied by several other delegates from a special ‘Conference of Minorities’. He stated that they wished to be available for discussion, whether invited or not, as Senanayake could not claim to speak for them and did not enjoy their confidence. There was also another delegation from Ceylon. The Indian Mercantile Association, who wished to discuss the Indian community in Ceylon, and their mercantile interests in particular. The Secretary of State had confidential discussions with D.S Senanayake, who said that he was expressing the views of the people of Ceylon.

G.G. Ponnambalam did finally see the Secretary of State for half an hour on 10 September 1945. There is a record of this meeting in the Colonial office document CO 54/987/1)no 62 of 11.9.1945. The contents of this minute are entertaining. Ponnambalam began by stating that he had no objection to D.S.Senanayake being consulted in his capacity as Leader of the House. Secretary of State had interrupted to point out that that was precisely why D.S. had been invited.

Ponnambalam thereafter stated that Senanayake had ‘no mandate whatsoever to represent the views of all five groups in Ceylon, and could not be expected to put forward views held the minority groups with which he was not in sympathy. ‘ Also that the British government would be influenced by him and be. thus biased towards the majority Sinhalese community. He could not_ understand why British had invited ‘the one man who instigated and led the boycott of: the Soulbury Commission in Ceylon ,” Ponnambalam maintained that Senanayake was anxious to prevent the Soulbury Commission hearing the view of the considerable minority groups in Ceylon.

At this point the listeners had inquired whether Ponnambalam represented the four minority groups. He replied that in theory he did not. He did however hold a mandate from about 1 million Tamils and thought that there was already sufficient evidence to show that his views were the views of all the minorities.

Ponnambalam had pointed out that under limited franchise which operated between 1834 and 1931, the Sinhalese had never held more than 50 of the seats. But after universal franchise came in, the Sinhalese kept getting a majority. His listeners had inquired how Ponnambalam intended to rectify matters since he too had approved of universal franchise. Ponnambalam suggested weighted representation for minorities such as had been proposed for the Muslims in India. Secretary of State pointed out that the Muslims in India had turned down the idea. Thereafter 5ecretary of State departed and Creech Jones who was left had a few more words with Ponnambalam which ‘got nowhere’. On 19 November 1945, Sidebotham commented ” Ponnambalam is still on our doorstep. He will go back a sadder and I hope, a wiser man”.

However Ponnambalam was not that easily quelled. When the Soulbury Report was published, he had plenty to say about it. He sent a long letter of complaint to the Colonial Office protesting against the Soulbury recommendations The main point in this lengthy memorandum is that the minorities should have been, given special status in the Soulbury reforms. “The Tamils (Ceylon and Indian) who are more than 25 of the population maybe given such weightage as to receive one-third (33) of the seats.”. There is no indication that there was any official response to this memorandum.

In this letter he also provided an analysis of Ceylonese society. the people of Ceylon were not a single entity. The population was heterogeneous. The social. structure was founded upon a communal basis and the needs of the various communities differed widely. it was , he said, a plural society of antagonistic communities and the principle problem of government is the protection of minorities.

Of the Minorities, the Tamils form the most important entity; they were the original habitants and rulers of the Island who established independent Kingdoms and even exercise sway over the entire Island over a long period of years. They remember With pride that the Kings of the Singalese were largely of Tamil extraction and that for quite a century till the British occupation the ruling dynasty was wholly Tamil. They Impressed their culture and policy on the Singalese and have been in the main, responsible for the political advancement of the country. In the economic sphere it was British capital and Tamil manpower that came over from South India that have contributed very largely to the development of the land in the plantation industries, Ponnambalam concluded.”

The Soulbury reforms appeared as a White paper in the State Council of Ceylon, and was passed with a generous majority, the Tamils councilors voting for it. Soon after, in a letter dated 13. November 1945, the Secretary of the All Ceylon Tamil Congress, sent a statement to Britain, explaining that they only voted to ensure independence through Dominion status. That otherwise they were against this White Paper. ACTC spoke of the need for ‘concrete proposals for safeguarding the Tamil position’ and the ‘political extinction of the Tamil community in Ceylon’ The Tamil Congress had convened a special session in Colombo to debate this matter.

In January 1946, Sivasubramaniam, Secretary of the All Ceylon Tamil Congress sent a letter to Britain criticizing the proposed constitution for Ceylon. he complained about the possibility of an ‘immutable succession of Sinhalese Buddhist Prime Ministers.’, of rule by one community, that the rule of a Singhalese oligarchy was disastrous to a people of the stature and culture of the Tamils, that an ethnic pact should have been decided on, that the Tamils be given an effective share in government Further that the Tamil people ‘refuse to believe that the British government ( would) impose a constitution on an unwilling people’ or that it would watch the political extinction of the Tamil community in Ceylon. Britain was reminded of the Arabs and Jews in Palestine, and also reminded that there were 40 million Tamils in India watching all this. There is no indication that Britain took any notice of these observations either.

Independence was granted and Ceylon prepared for its big day. A flag was needed. The national flag of Ceylon became an issue in 1947. The obvious choice was the Sinhala flag rescued from some hospital in Chelsea, London. S. J. V. Chelvanayagam, Member for Kankesanturai opposed the lion flag, saying it was not a national flag, it is the Sinhala flag. K. Kanagaratnam, Member for Vadukoddai seconded it. Vanniasingham (Kopay) and K.V. Nadarajah (Bandarawela) also spoke. C. Suntheralingam said ‘hoist the lion flag and then change it afterwards.’

- Sri Nissanka observed that ‘we are now under a new dispensation. The lion flag is the Sinhala flag, not the national flag and other communities can’t be asked to salute it’. Others said that the lion flag was only the royal standard, not the national flag. We need a new flag to represent the multi- ethnic character of the country, a flag for all communities, they said. The national flag should be Lion, Nandi and crescent of the Muslims said Chelvanayakam. This was rejected. Prime Minister referred this matter to a committee of both houses. Its Tamil members were G.G. Ponnambalam and S. Nadesan. The committee recommended that that the national flag of Ceylon should be the lion flag of the Sinhala kingdom, with vertical stripes in green saffron to represent the Tamils and Muslims.

However, the lion flag was hoisted at the Independence function. It was also flown at the opening of Parliament. Prime Minister D. S. Senanayake and other authorities had prohibited any communal flags being hoisted on Independence Day. Those who objected to the Lion flag could raise the Union Jack. All state buildings flew the Lion flag and Union Jack. But Jaffna had flown the Nandi (bull) flag and in Colombo several Tamil leaders, including Deputy Solicitor General M. Thiruchelvam flew the Nandi flag on their vehicles. H.L.D.Mahindapala also recalls that On Feb 4, 1949 M Thiruchelvam, father of Neelan Thiruchelvam, was in a car which flew the Nandi flag. This shows that the Tamil separatist movement was already in existence and gathering momentum at the time of independence.

Tamil Separatist Movement said that the Sri Lankan Tamils ‘consented’ to the granting of independence in 1947, on the understanding that there would be no discrimination against the minorities. If they wished to, the Tamils could have asked for, and got independence as a separate entity. Jaffna had originally been a separate kingdom, and it was this kingdom which went under the Portuguese and Dutch.

This essay shows that that was not the case. There is no mention of the ‘Kingdom of Jaffna’ in the Tamil utterances on constitutional reform. Further, during the granting of independence, Britain was concerned about losing its control of the Indian Ocean. Britain was hardly likely to create two countries at once, when they were scared that even the one independent state would start kicking eventually and oppose Britain. The Tamil protestations against the majority Sinhalese were considered, and then dismissed.

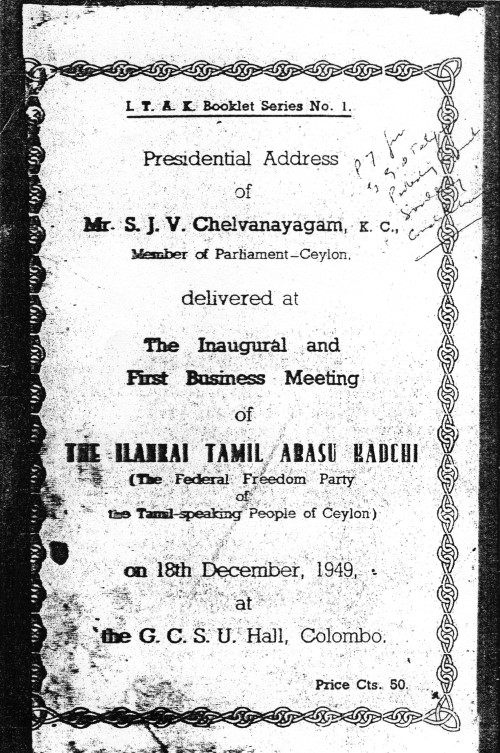

One year after Independence, S. J. V. Chelvanayakam, C. Vanniasingam, and Senator E. M. V. Naganathan founded the Illankai Tamil Arasu Kadchi. The inaugural meeting which was also the first business meeting was at the GCSU Hall in Maradana on 18 December 1949. Maradana was selected instead of Jaffna because the politically alert Tamils were in Colombo. Many were clerks in the GCSU. ITAK translated the name into English as Federal Party.” This was intended to mislead the Sinhalese. The correct translation is ‘Lanka Tamil state Party.’ This political party was committed to a separate state, not federalism.

I am unable to find the full text of the inaugural speech by Chelvanayakam. Here are excerpts. We have met together with the common aim of creating an organization to work for the attainment of freedom for the Tamil speaking people of Ceylon. A Unitary Government with present composition of legislature and structure of executive totally unacceptable to the Tamils. In the absence of a satisfactory alternative we demand the right of self-determination for the Tamil people.”

The Tamils leaders of the 1940s were very arrogant. They looked down on the Sinhalese. According to Sebastian Rasalingam, Ponnambalam had called the Sinhalese ‘racial half breeds’ as a meeting in Nawalapitiya in 1939. When universal suffrage was granted the Tamil leaders expressed indignation at the prospect of a Sinhalese takeover of Ceylon. Chelvanayakam is reported to have said ‘Sinhalese are too small to govern the Tamils’,. Chelvanayakam later canvassed for an exclusive Tamil university in the North. When questioned as to why it had to be exclusively Tamil, he had replied because the Tamils are more intelligent than the Sinhalese.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.