XI.

The Buddha’s Royal Patrons

“A treacherous bog it is, this patronage

Of bows and gifts and treats from wealthy folk.

‘Tis like a fine dart, bedded in the flesh.

For erring human hard to extricate.”—Mahākassapa Thera Gāthā (1053)

King Bimbisāra

King Bimbisāra, who ruled in Magadha with its capital at Rājagaha, was the Buddha’s first royal patron. Ascending the throne at the age of fifteen, he reigned for fifty-two years.

When Prince Siddhattha renounced the world and was seeking alms in the streets of Rājagaha as a humble ascetic, the king saw him from his palace and was highly impressed by his majestic appearance and dignified deportment. Immediately he sent messengers to ascertain who he was. On learning that he was resting after his meal under the Pāndavapabbata, the king, accompanied by his retinue, went up to the royal ascetic and inquired about his birthplace and ancestry.

The Ascetic Gotama replied:

“Just straight, O King, upon the Himalaya, there is, in the district of Kosala of ancient families, a country endowed with wealth and energy. I am sprung from that family which by clan belongs to the Solar dynasty, by birth to the Sākyas. I crave not for pleasures of the senses. Realising the evil of sensual pleasures and seeing renunciation as safe, I proceeded to seek the highest, for in that my mind rejoices. 164

Thereupon the king invited him to visit his kingdom after his enlightenment.

The Buddha meets King Bimbisāra

In accordance with the promise the Buddha made to King Bimbisāra before his enlightenment, he, with his large retinue of arahant disciples, went from Gayā to Rājagaha, the capital of the district of Magadha. Here he stayed at the Suppatittha shrine in a palm grove.

This happy news of the Buddha’s arrival in the kingdom and his high reputation as an unparalleled religious teacher soon spread in the city. The King, hearing of his arrival, came with a large number of his subjects to welcome the Buddha. He approached the Buddha, respectfully saluted him and sat at one side. Of his subjects some respectfully saluted him, some looked towards him with expression of friendly greetings, some saluted him with clasped hands, some introduced themselves, while others in perfect silence took their seats. As both the Buddha Gotama and the Venerable Kassapa were held in high esteem by the multitude they were not certain whether the Buddha was leading the holy life under or the latter under the former. The Buddha read their thoughts and questioned Venerable Kassapa as to why he had given up his fire-sacrifice. Understanding the motive of the Buddha’s question, he explained that he abandoned fire-sacrifice because he preferred the passionless and peaceful state of Nibbāna to worthless sensual pleasures. After this he fell at the feet of the Buddha and acknowledging his superiority said: “My teacher, Lord, is the Exalted One: I am the disciple. My teacher, Lord, is the Exalted One: I am the disciple.”

The devout people were delighted to hear of the conversion. The Buddha thereupon preached the Mahā Nārada Kassapa Jātaka 165 to show how in a previous birth when he was born as Nārada, still subject to passion, he converted Kassapa in a similar way.

Hearing the Dhamma expounded by the Buddha, the “eye of truth” 166 arose in them all. King Bimbisāra attained sotāpatti, and seeking refuge in the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha, invited the Buddha and his disciples to his palace for the meal on the following day. After the meal the king wished to know where the Buddha would reside. The Buddha replied that a secluded place, neither too far nor too close to the city, accessible to those who desire to visit him, pleasant, not crowded during the day, not too noisy at night, with as few sounds as possible, airy and fit for the privacy of men, would be suitable.

The king thought that his Bamboo Grove would meet all such requirements. Therefore in return for the transcendental gift the Buddha had bestowed upon him, he gifted for the use of the Buddha and the Sangha the park with this ideally secluded bamboo grove, also known as ‘The Sanctuary of the Squirrels.’ It would appear that this park had no building for the use of bhikkhus but was filled with many shady trees and secluded spots. However, this was the first gift of a place of residence for the Buddha and his disciples. The Buddha spent three successive rainy seasons and three other rainy seasons in this quiet Veḷuvanārāma. 167

After his conversion the king led the life of an exemplary monarch observing uposatha regularly on six days of the month.

Kosala Devi, daughter of King Mahā Kosala, and sister of King Pasenadi Kosala, was his chief loyal queen. Ajātasattu was her son. Khemā who, through the ingenuity of the king, became a follower of the Buddha and who later rose to the position of the first female disciple of the order of nuns, was another queen.

Though he was a pious monarch, yet, due to his past evil kamma, he had a very sad and pathetic end.

Prince Ajātasattu, successor to the throne, instigated by wicked Devadatta Thera, attempted to kill him and usurp the throne. The unfortunate prince was caught red-handed, and the compassionate father, instead of punishing him for his brutal act, rewarded him with the coveted crown.

The ungrateful son showed his gratitude to his father by casting him into prison in order to starve him to death. His mother alone had free access to the king daily. The loyal queen carried food concealed in her waist-pouch. To this the prince objected. Then she carried food concealed in her hair-knot. The prince resented this too. Later she bathed herself in scented water and besmeared her body with a mixture of honey, butter, ghee, and molasses. The king licked her body and sustained himself. The over-vigilant prince detected this and ordered his mother not to visit his father.

King Bimbisāra was without any means of sustenance, but he paced up and down enjoying spiritual happiness as he was a sotāpanna. Ultimately the wicked son decided to put an end to the life of his noble father. Ruthlessly he ordered his barber to cut open his soles and put salt and oil thereon and make him walk on burning charcoal.

The King, who saw the barber approaching, thought that the son, realising his folly, was sending the barber to shave his grown beard and hair and release him from prison. Contrary to his expectations, he had to meet an untimely sad end. The barber mercilessly executed the inhuman orders of the barbarous prince. The good King died in great agony. On that very day a son was born unto Ajātasattu. Letters conveying the news of birth and death reached the palace at the same time.

The letter conveying the happy news was first read. Lo, the love he cherished towards his first-born son was indescribable! His body was thrilled with joy and the paternal love penetrated up to the very marrow of his bones.

Immediately he rushed to his beloved mother and questioned: “Mother dear, did my father love me when I was a child?”

“What say you, son! When you were conceived in my womb, I developed a craving to sip some blood from the right hand of your father. This I dare not say. Consequently I grew pale and thin. I was finally persuaded to disclose my inhuman desire. Joyfully your father fulfilled my wish, and I drank that abhorrent potion. The soothsayers predicted that you would be an enemy of your father. Accordingly you were named Ajātasattu (“unborn enemy.”)

I attempted to effect a miscarriage, but your father prevented it. After you were born, again I wanted to kill you. Again your father interfered. On one occasion you were suffering from a boil in your finger, and nobody was able to lull you into sleep. But your father, who was administering justice in his royal court, took you into his lap and caressing you sucked the boil. Lo, inside the mouth it burst open. O, my dear son, that pus and blood! Yes, your affectionate father swallowed it out of love for you.”

Instantly he cried, “Run and release, release my beloved father quickly!”

His father had closed his eyes for ever.

The other letter was then placed in his hand.

Ajātasattu shed hot tears. He realised what paternal love was only after he became a father himself.

King Bimbisāra died and was immediately after born as a deva named Janavasabha in the Cātummahārājika heaven.

Later, Ajātasattu met the Buddha and became one of his distinguished lay followers and took a leading part in the holding of the first convocation.

King Pasenadi Kosala

King Pasenadi Kosala, the son of King Mahā Kosala, who reigned in the kingdom of Kosala with its capital at Sāvatthī, was another royal patron of the Buddha. He was a contemporary of the Buddha, and owing to his proficiency in various arts, he had the good fortune to be made king by his father while he was alive.

His conversion must probably have taken place during the very early part of the Buddha’s ministry. In the Saṃyutta Nikāya it is stated that once he approached the Buddha and questioning him about his perfect enlightenment referred to him as being young in years and young in ordination. 168

The Buddha replied—”There are four objects, O Mahārāja, that should not be disregarded or despised. They are a Khattiya (a warrior prince), a snake, fire, and a bhikkhu (mendicant monk). 169

Then he delivered an interesting sermon on this subject to the king. At the close of the sermon the king expressed his great pleasure and instantly became a follower of the Buddha. Since then till his death he was deeply attached to the Buddha. It is said that on one occasion the king prostrated himself before the Buddha and stroked his feet covering them with kisses. 170

His chief queen, Mallikā a very devout and wise lady, well versed in the Dhamma, was greatly responsible for his religious enthusiasm. Like a true friend, she had to act as his religious guide on several occasions.

One day the king dreamt sixteen unusual dreams and was greatly perturbed in mind, not knowing their true significance. His brahmin advisers interpreted them to be dreams portending evil and instructed him to make an elaborate animal sacrifice to ward off the dangers resulting therefrom. As advised he made all necessary arrangements for this inhuman sacrifice which would have resulted in the loss of thousands of helpless creatures. Queen Mallikā, hearing of this barbarous act about to be perpetrated, persuaded the king to get the dreams interpreted by the Buddha whose understanding infinitely surpassed that of those worldly brahmins. The king approached the Buddha and mentioned the object of his visit. Relating the sixteen dreams 171 he wished to know their significance, and the Buddha explained their significance fully to him.

Unlike King Bimbisāra, King Kosala had the good fortune to hear several edifying and instructive discourses from the Buddha. In the Saṃyutta Nikāya there appears a special section called the Kosala Saṃyutta 172 in which are recorded most of the discourses and talks given by the Buddha to the king.

Once while the king was seated in the company of the Buddha, he saw some ascetics with hairy bodies and long nails passing by, and rising from his seat respectfully saluted them calling out his name to them: “I am the king, your reverences, the Kosala, Pasenadi.” When they had gone he came back to the Buddha and wished to know whether they were arahants or those who were striving for arahantship. The Buddha explained that it was difficult for ordinary laymen enjoying material pleasures to judge whether others are arahants or not and made the following interesting observations:

“It is by association (saṃvāsena) that one’s conduct (sīla) is to be understood, and that, too, after a long time and not in a short time, by one who is watchful and not by a heedless person, by an intelligent person and not by an unintelligent one. It is by conversation (serivihārena) that one’s purity (soceyyaṃ) is to be understood. It is in time of trouble that one’s fortitude is to be understood. It is by discussion that one’s wisdom is to be understood, and that, too, after a long time and not in a short time, by one who is watchful and not by a heedless person, by an intelligent person and not by an unintelligent one.”

Summing up the above, the Buddha uttered the following verses:

Not by his outward guise is man well known.

In fleeting glance let none place confidence.

In garb of decent well-conducted folk

The unrestrained live in the world at large.

As a clay earring made to counterfeit,

Or bronze half penny coated over with gold,

Some fare at large hidden beneath disguise,

Without, comely and fair; within, impure. 173

King Kosala, as ruler of a great kingdom, could not possibly have avoided warfare, especially with kings of neighbouring countries. Once he was compelled to fight with his own nephew, King Ajātasattu, and was defeated. Hearing it, the Buddha remarked:

“Victory breeds hatred.

The defeated live in pain.

Happily the peaceful live, giving up victory and defeat.” 174

On another occasion King Kosala was victorious and he confiscated the whole army of King Ajātasattu, saving only him. When the Buddha heard about this new victory, he uttered the following verse, the truth of which applies with equal force to this modern war-weary world as well:

“A man may spoil another, just so far

As it may serve his ends, but when he’s spoiled

By others he, despoiled, spoils yet again.

So long as evil’s fruit is not matured,

The fool doth fancy ‘now’s the hour, the chance!’

But when the deed bears fruit, he fareth ill.

The slayer gets a slayer in his turn;

The conqueror gets one who conquers him;

Th’abuser wins abuse, th’annoyer, fret.

Thus by the evolution of the deed,

A man who spoils is spoiled in his turn.” 175

What the Buddha has said to King Kosala about women is equally interesting and extremely encouraging to womankind. Once while the king was engaged in a pious conversation with the Buddha, a messenger came and whispered into his ear that Queen Mallikā had given birth to a daughter. The king was not pleased at this unwelcome news. In ancient India, as it is to a great extent today, a daughter is not considered a happy addition to a family for several selfish reasons as, for instance, the problem of providing a dowry. The Buddha, unlike any other religious teacher, paid a glowing tribute to women and mentioned four chief characteristics that adorn a woman in the following words:

“Some women are indeed better (than men).

Bring her up, O Lord of men.

There are women who are wise, virtuous,

who regard mother-in-law as a goddess, and who are chaste.

To such a noble wife may be born a valiant son,

a lord of realms, who would rule a kingdom.” 176

Some women are even better than men. “Itthi hi pi ekacciyā seyyā” were the actual words used by the Buddha. No religious teacher has made such a bold and noble utterance especially in India, where women are not held in high esteem.

Deeply grieved over the death of his old grandmother, aged one hundred and twenty years, King Kosala approached the Buddha and said that he would have given everything within his means to save his grandmother who had been as a mother to him. The Buddha consoled him, saying:

“All beings are mortal; they end with death, they have death in prospect. All the vessels wrought by the potter, whether they are baked or unbaked, are breakable; they finish broken, they have breakage in prospect.” 177

The king was so desirous of hearing the Dhamma that even if affairs of state demanded his presence in other parts of the kingdom, he would avail himself of every possible opportunity to visit the Buddha and engage in a pious conversation. The Dhammacetiya and Kannakatthala Suttas 178 were preached on such occasions.

King Kosala’s chief consort, the daughter of a garland-maker, predeceased him. A sister of King Bimbisāra was one of his wives. One of his sisters was married to King Bimbisāra and Ajātasattu was her son.

King Kosala had a son named Viḍūḍabha who revolted against him in his old age. This son’s mother was the daughter of Mahānāma the Sākya, who was related to the Buddha, and his grandmother was a slave-girl. This fact the king did not know when he took her as one of his consorts. Hearing a derogatory remark made by Sākyas about his ignoble lineage, Viḍūḍabha took vengeance by attempting to destroy the Sākya race. Unfortunately it was due to Viḍūḍabha that the king had to die a pathetic death in a hall outside the city with only a servant as his companion. King Kosala predeceased the Buddha.

XII.

The Buddha’s Ministry

“Freed am I from all bonds, whether divine or human.

You, too, O bhikkhus, are freed from all bonds.”

The Buddha’s beneficent and successful ministry lasted forty-five years. From his 35th year, the year of his enlightenment, till his death in his 80th year, he served humanity both by example and by precept. Throughout the year he wandered from place to place, at times alone, sometimes accompanied by his disciples, expounding the Dhamma to the people and liberating them from the bonds of saṃsāra. During the rainy season (vassāna) from July to November, owing to incessant rains, he lived in retirement as was customary with all ascetics in India in his time.

In ancient times, as today, three regular seasons prevailed in India, namely vassāna (rainy), hemanta (swinter), and gimhāna (hot). The vassāna or rainy season starts in Ásālha and extends up to Assayuga, that is, approximately from the middle of July to the middle of November.

During the vassāna period, due to torrential rains, rivers and streams usually get flooded, roads get inundated, communications get interrupted and people as a rule are confined to their homes and villages and live on what provisions they have collected during the previous seasons. During this time the ascetics find it difficult to engage in their preaching tours, wandering from place to place. An infinite variety of vegetable and animal life also appears to such an extent that people could not move about without unconsciously destroying them. Accordingly all ascetics including the disciples of the Buddha, used to suspend their itinerant activities and live in retirement in solitary places. As a rule the Buddha and his disciples were invited to spend their rainy seasons either in a monastery or in a secluded park. Sometimes, however, they used to retire to forests. During these rainy seasons people flocked to the Buddha to hear the Dhamma and thus availed themselves of his presence in their vicinity to their best advantage.

The First Twenty Years

First Year at Benares

After expounding the Dhammacakka Sutta to his first five disciples on the Ásālha full moon day, he spent the first rainy season in the Deer Park at Isipatana, near Benares. Here there was no special building where he could reside. Yasa’s conversion took place during this retreat.

Second, Third, and Fourth Years at Rājagaha

Rājagaha was the capital of the kingdom of Magadha where ruled King Bimbisāra. When the Buddha visited the king, in accordance with a promise made by him before his enlightenment, he offered his Bamboo Grove (veluvana) to the Buddha and his disciples. This was an ideal solitary place for monks as it was neither too far nor too near to the city. Three rainy seasons were spent by the Buddha in this quiet grove.

Fifth Year at Vesāli

During this year while he was residing in the Pinnacle Hall at Mahāvana near Vesāli, he heard of the impending death of King Suddhodana and, repairing to the king’s death chamber, preached the Dhamma to him. Immediately the king attained arahantship. For seven days thereafter he experienced the bliss of emancipation then passed away.

It was in this year that the bhikkhuṇī order was founded at the request of Mahā Pajāpati Gotamī. After the cremation of the king, when the Buddha was temporarily residing at Nigrodhārāma, Mahā Pajāpati Gotamī approached the Buddha and begged permission for women to enter the order. But the Buddha refused and returned to the Pinnacle Hall at Rājagaha. Mahā Pajāpati Gotamī was so intent on renouncing the world that she, accompanied by many Sākya and Koliya ladies, walked all the way from Kapilavatthu to Rājagaha and, through the intervention of Venerable Ánanda, succeeded in entering the order. 179

Sixth Year at Mankula Hill in Kosambi, near Allahabad

Just as he performed the “twin wonder” (yamaka pāihāriya) 180 to overcome the pride of his relatives at Kapilavatthu, even so did he perform it for the second time at Mankula Hill to convert his alien followers.

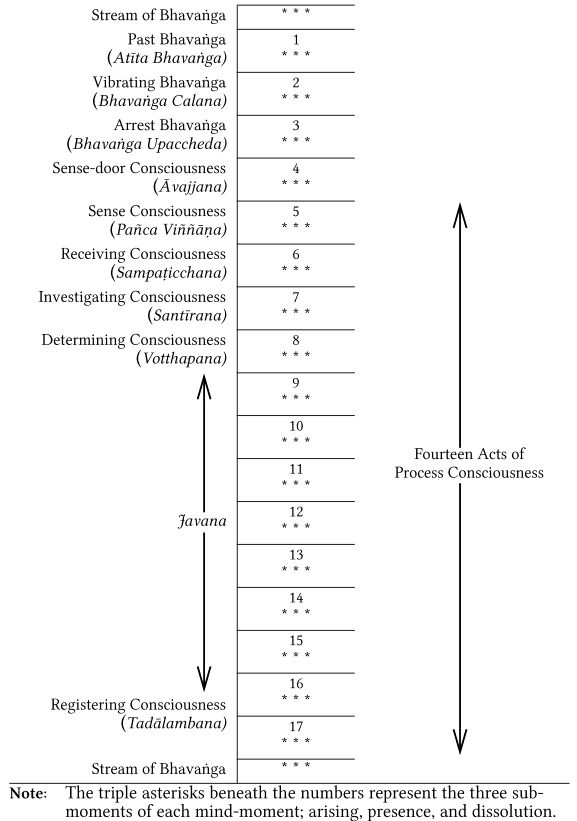

Seventh Year at Tāvatiṃsa Heaven

A few days after the birth of Prince Siddhattha Queen Mahā Māyā died and was born as a deva (god) in the Tusita Heaven. In this seventh year, during the three rainy months, the Buddha preached the Abhidhamma 181 to the devas of the Tāvatiṃsa Heaven where the mother-Deva repaired to hear him. Daily he came to earth and gave a summary of his sermon to the Venerable Sāriputta who in turn expounded the same doctrine in detail to his disciples. What is embodied in the present Abhidhamma Piṭaka is supposed to be this detailed exposition of the Dhamma by him.

It is stated that, on hearing these discourses, the deva who was his mother attained the first stage of sainthood.

Eighth Year at Bhesakalā Forest, near Suṃsumāra Rock, in the Bhagga District

Ninth Year at Kosambi

It was in this year that Māgandiyā harboured a grudge against the Buddha and sought an opportunity to dishonour him.

Māgandiyā was a beautiful maiden. Her parents would not give her in marriage as the prospective suitors, in their opinion, were not worthy of their daughter. One day as the Buddha was surveying the world, he perceived the spiritual development of the parents. Out of compassion for them he visited the place where the father of the girl was tending the sacred fire. The brahmin, fascinated by the Buddha’s physical beauty, thought that he was the best person to whom he could give his daughter in marriage and requesting him to stay there until his arrival, hurried home to bring his daughter. The Buddha in the meantime stamped his footprint on that spot and moved to a different place. The brahmin and his wife, accompanied by their daughter who was dressed in her best garments, came to that spot and observed the footprint. The wife who was conversant with signs said that it was not the footprint of an ordinary man but of a pure person who had eradicated all passions. The Brahmin ridiculed the idea, and, noticing the Buddha at a distance offered his daughter unto him. The Buddha describing how he overcame his passions said:

“Having seen Taṇhā, Arati, and Ragā, 182

I had no pleasure for the pleasures of love.

What is this body, filled with urine and dung?

I should not be willing to touch it, even with my foot.” 183

Hearing his Dhamma, the brahmin and his wife attained anāgāmi, the third stage of sainthood. But proud Māgandiya felt insulted and she thought to herself, “If this man has no need of me, it is perfectly proper for him to say so, but he declares me to be full of urine and dung. Very well, by virtue of birth, lineage, social position, wealth, and the charm of youth that I possess I shall obtain a husband who is my equal, and then I shall know what ought to be done to the monk Gotama.”

Enraged by the words of the Buddha, she conceived a hatred towards him. Later she was given as a consort to the king of Udena. Taking advantage of her position as one of the royal consorts, she bribed people and instigated them to revile and drive the Buddha out of the city. When the Buddha entered the city, they shouted at him, saying: “You are a thief, a simpleton, a fool, a camel, an ox, an ass, a denizen of hell, a beast. You have no hope of salvation. A state of punishment is all that you can look forward to.”

Venerable Ánanda, unable to bear this filthy abuse, approached the Buddha and said, “Lord, these citizens are reviling and abusing us. Let us go elsewhere.”

“Where shall we go, Ánanda?” asked the Buddha.

“To some other city, Lord,” said Ánanda.

“If men revile us there, where shall we go then?” inquired the Buddha.

“To still another city, Lord,” said Ánanda.

“Ánanda, one should not speak thus. Where a difficulty arises, right there should it be settled. Only under those circumstances is it permissible to go elsewhere. But who are reviling you, Ánanda?” questioned the Buddha.

“Lord, everyone is reviling us, slaves and all,” replied Ánanda. Admonishing Venerable Ánanda to practise patience, the Buddha said:

“As an elephant in the battle-field withstands the arrows shot from a bow, even so will I endure abuse. Verily, most people are undisciplined.”

“They lead the trained horses or elephants to an assembly. The king mounts the trained animal. The best among men are the disciplined who endure abuse.”

“Excellent are trained mules, so are thorough-bred horses of Sindh and noble tusked elephants; but the man who is disciplined surpasses them all.” 184

Again he addressed Venerable Ánanda and said, “Be not disturbed. These men will revile you only for seven days, and, on the eighth day they will become silent. A difficulty encountered by the Buddhas lasts no longer than seven days.” 185

Tenth Year at Pārileyyaka Forest

While the Buddha was residing at Kosambi, a dispute arose between two parties of bhikkhus—one versed in the Dhamma, the other in the Vinaya—with respect to the transgression of a minor rule of etiquette in the lavatory. Their respective supporters also were divided into two sections.

Even the Buddha could not settle the differences of these quarrelsome monks. They were adamant and would not listen to his advice. The Buddha thought: “Under present conditions the jostling crowd in which I live makes my life one of discomfort. Moreover these monks pay no attention to what I say. Suppose I were to retire from the haunts of men and live a life of solitude.” In pursuance of this thought, without even informing the Sangha, alone he retired to the Pārileyyaka Forest and spent the rainy season at the foot of a beautiful Sal tree.

It was on this occasion, according to the story, that an elephant and a monkey ministered to his needs. 186

Eleventh Year at Ekanālā, Brahmin Village

The following Kasībhāradvājā Sutta 187 was delivered here:

On one occasion the Buddha was residing at Ekanālā in Dakkhiṇagiri, the brahmin village in Magadha. At that time about five-hundred ploughs belonging to Kasībhāradvāja brahmin were harnessed for the sowing. Thereupon the Exalted One, in the forenoon, dressed himself and taking bowl and robe went to the working place of the brahmin. At that time the distribution of food by the brahmin was taking place. The Buddha went to the place where food was being distributed and stood aside. The brahmin Kasībhāradvāja saw the Buddha waiting for alms. Seeing him, he spoke thus: “I, O ascetic, plough and sow; and having ploughed and sown, I eat. You also, O ascetic, should plough and sow; and having ploughed and sown, you should eat.”

“I, too, O brahmin, plough and sow; having ploughed and sown, I eat,” said the Buddha.

“But we see not the Venerable Gotama’s yoke, or plough, or ploughshare, or goad, or oxen, albeit the Venerable Gotama says, “I too plough and sow; and having ploughed and sown, I eat,” remarked the brahmin.

Then the brahmin Bhāradvāja addressed the Exalted One thus:

“A farmer you claim to be, but we see none of your tillage. Being questioned about ploughing, please answer us so that we may know your ploughing.”

The Buddha answered:

“Confidence (saddhā) is the seed, discipline (tapo) is the rain, wisdom (paññā) my yoke and plough, modesty (hiri) the pole of my plough, mind (mano) the rein, and mindfulness (sati) my ploughshare and goad.

“I am controlled in body, controlled in speech, temperate in food. With truthfulness I cut away weeds. Absorption in the Highest (arahantship) is the release of the oxen.

“Perseverance (viriya) is my beast of burden that carries me towards the bond-free state (āna). Without turning it goes, and having gone it does not grieve.

“Thus is the tilling done: it bears the fruit of deathlessness. Having done this tilling, one is freed from all sorrow.”

Thereupon the brahmin Kasībhāradvāja, filling a large bronze bowl with milk-rice, offered it to the Exalted One, saying “May the Venerable Gotama eat the milk-rice! The Venerable Gotama is a farmer, since the Venerable Gotama tills a crop that bears the fruit of deathlessness.”

The Exalted One, however, refused to accept this saying:

“What is obtained by reciting verses is not fit to be eaten by me. This, O brahmin, is not the rule of seers. The Enlightened reject such food. While this principle lasts, this is the livelihood.

“Serve the unique, cankerless, great sage of holy calm with other kind of food and drink, for he is like a field to him that desires to sow good deeds.”

Twelfth Year at Verañjā

A brahmin of Verañjā, hearing that the Buddha was residing at Verañjā near Naleru’s Nimba tree with a large company of his disciples, approached him and raised several questions with regard to his conduct. The brahmin was so pleased with his answers that he became a follower of the Buddha and invited him and his disciples to spend the rainy season at Verañjā. The Buddha signified his assent as usual by his silence.

Unfortunately at this particular time there was a famine at Verañjā and the Buddha and his disciples were compelled to live on food intended for horses. A horse-dealer very kindly provided them with coarse food available, and the Buddha partook of such food with perfect equanimity.

One day, during this period, Venerable Sāriputta, arising from his solitary meditation, approached the Buddha and respectfully questioned him thus: “Which Buddha’s dispensation endured long and which did not?”

The Buddha replied that the dispensations of the Buddhas Vipassi, Sikhī, and Vessabhū did not endure long. While the dispensations of the Buddhas Kakusandha, Koṇāgamana, and Kassapa endured long. 188

The Buddha attributed this to the fact that some Buddhas made no great effort in preaching the Dhamma in detail and promulgated no rules and regulations for the discipline of the disciples, while other Buddhas did so.

Thereupon Venerable Sāriputta respectfully implored the Buddha to promulgate the fundamental precepts (pātimokkha) for the future discipline of the Sangha so that the holy life may endure long.

“Be patient, Sāriputta, be patient,” said the Buddha and added:

“The Tathāgata alone is aware of the time for it. Until certain defiling conditions arise in the Sangha the Tathāgata does not promulgate means of discipline for the disciples and does not lay down the fundamental precepts (pātimokkha). When such defiling conditions arise in the Sangha, only then the Tathāgata promulgates means of discipline and lays down the fundamental precepts for the disciples in order to eradicate such defilements.

“When, Sāriputta, the Sangha attains long standing (rattaññū-mahattaṃ), full development (vepulla-mahattaṃ), great increase in gains (lābhagga-mahattaṃ😉 and greatness in erudition (bahussuta-mahattaṃ), defiling conditions arise in the Sangha. Then does the Tathāgata promulgate means of discipline and the fundamental precepts to prevent such defilements.

“Sāriputta, the order of disciples is free from troubles, devoid of evil tendencies, free from stain, pure, and well established in virtue. The last of my five-hundred disciples is a sotāpanna (stream-winner) not liable to fall, steadfast and destined for enlightenment.” 189

(The rainy season at Verañjā forms the subject of the Introduction to the Pārājikā Book of the Vinaya Piṭaka.)

At the end of this rainy season the Buddha went on a preaching tour to Soreyya, Saṇkassa, Kaṇṇakujja, Payāga, and then, crossing the river, stayed some time in Benares and returned thence to Vesāli to reside at the Pinnacle Hall in Mahāvana.

Thirteenth Year was spent at Cāliya Rock

Fourteenth Year at Jetavana Monastery, Sāvatthī

The Venerable Rāhula received his higher ordination at this time on the completion of his twentieth year.

Fifteenth Year at Kapilavatthu

The pathetic death of King Suppabuddha who was angry with the Buddha for leaving his daughter, Princess Yasodharā, occurred in this year. It may be mentioned that the Buddha spent only one rainy season in his birthplace.

Sixteenth Year at the city of Áḷavi

The conversion of Áḷavaka the demon, 190 who feasted on human flesh, took place in this year.

Áḷavaka, a ferocious demon, was enraged to see the Buddha in his mansion. He came up to him and asked him to depart. “Very well, friend,” said the Buddha and went out. “Come in,” said he. The Buddha came in. For the second and third time he made the same request and the Buddha obeyed. But when he commanded him for the fourth time, the Buddha refused and asked him to do what he could.

“Well, I will ask you a question,” said Áḷavaka, “If you will not answer, I will scatter your thoughts, or tear out your heart, or take you by your feet and fling you across the Ganges.”

“Nay, friend,” replied the Buddha, “I see not in this world inclusive of gods, brahmas, ascetics, and brahmins, amongst the multitude of gods and men, any who could scatter my thoughts, or tear out my heart, or take me by my feet and fling me across the Ganges. However, friend, ask what you wish.”

Áḷavaka then asked the following questions:

“Herein, which is man’s best possession?

Which well practised yields happiness?

Which indeed is the sweetest of tastes?

How lived, do they call the best life?”

To these questions the Buddha answered thus:

“Herein confidence is man’s best possession.

Dhamma well practised yields happiness.

Truth indeed is the sweetest of tastes.

Life lived with understanding is best, they say.”

Áḷavaka next asked the Buddha:

“How does one cross the flood?

How does one cross the sea?

How does one overcome sorrow?

How is one purified?”

The Exalted One replied:

“By confidence one crosses the flood,

by heedfulness the sea.

By effort one overcomes sorrow,

by wisdom is one purified.”

Áḷavaka then inquired:

“How is wisdom gained?

How are riches found?

How is renown gained?

How are friends bound?

Passing from this world to the next,

how does one not grieve?” 191

In answer the Buddha said:

“The heedful, intelligent person of confidence gains wisdom by hearing the Dhamma of the Pure Ones that leads to Nibbāna. He who does what is proper, persevering and strenuous, gains wealth. By truth one attains to fame. Generosity binds friends.

“That faithful householder who possesses these four virtues—truthfulness, good morals, courage and liberality—grieves not after passing away.

“Well, ask many other ascetics and brahmins whether there is found anything greater than truthfulness, self-control, generosity, and patience.

Understanding well the meaning of the Buddha’s words, Áḷavaka said:

“How could I now ask diverse ascetics and brahmins? Today I know what is the secret of my future welfare.

“For my own good did the Buddha come to Áḷavi. Today I know where gifts bestowed yield fruit in abundance. From village to village, from town to town will I wander honouring the Fully Enlightened One and the perfection of the sublime Dhamma.”

Seventeenth Year was spent at Rājagaha

Eighteenth Year was spent at Cāliya Rock

Nineteenth and Twentieth years were spent at Rājagaha

Buddha and Aṇgulimāla

It was in the 20th year that the Buddha converted the notorious murderer Aṇgulimāla. 192 Ahiṃsaka (Innocent) was his original name. His father was chaplain to the king of Kosala. He received his education at Taxila, the famous educational centre in the olden days, and became the most illustrious and favourite pupil of his renowned teacher. Unfortunately his colleagues grew jealous of him, concocted a false story, and succeeded in poisoning the teacher’s mind against him. The enraged teacher, without any investigation, contrived to put an end to his life by ordering him to fetch a thousand human right-hand fingers as teacher’s honorarium. In obedience to the teacher, though with great reluctance, he repaired to the Jālinī forest, in Kosala, and started killing people to collect fingers for the necessary offering. The fingers thus collected were hung on a tree, but as they were destroyed by crows and vultures he later wore a garland of those fingers to ascertain the exact number. Hence he was known by the name Aṇgulimāla (Finger-wreathed). When he had collected 999 fingers, so the books state, the Buddha appeared on the scene. Overjoyed at the sight, because he thought that he could complete the required number by killing the great ascetic, he stalked the Buddha drawing his sword. The Buddha by his psychic powers created obstacles on the way so that Aṇgulimāla would not be able to get near him although he walked at his usual pace. Aṇgulimāla ran as fast as he could but he could not overtake the Buddha. Panting and sweating, he stopped and cried: “Stop, ascetic.” The Buddha calmly said: “Though I walk, yet have I stopped. You too, Aṇgulimāla stop.” The bandit thought —”These ascetics speak the truth, yet he says he has stopped, whereas it is I who have stopped. What does he mean?”

Standing, he questioned him:

“You who are walking, monk, say: ‘I have stopped!’

And me you say, who have stopped, I have not stopped!

I ask you, monk, what is the meaning of your words?

How can you say that you have stopped but I have not?”

The Buddha sweetly replied:

“Yes, I have stopped, Aṇgulimāla, forever.

Towards all living things renouncing violence;

You hold not your hand against your fellow men,

Therefore I have stopped, but you still go on.”

Aṇgulimāla’s good kamma rushed up to the surface. He thought that the great ascetic was none other but the Buddha Gotama who out of compassion had come to help him.

Straightaway he threw away his armour and sword and became a convert. Later, as requested by him he was admitted into the Noble order by the Buddha with the mere utterance, ‘Come, O bhikkhu!’ (ehi bhikkhu).

News spread that Aṇgulimāla had become a bhikkhu. The king of Kosala, in particular, was greatly relieved to hear of his conversion because he was a veritable source of danger to his subjects.

But Aṇgulimāla had no peace of mind, because even in his solitary meditation he used to recall memories of his past and the pathetic cries of his unfortunate victims. As a result of his evil kamma, while seeking alms in the streets he would become a target for stray stones and sticks and he would return to the monastery ‘with broken head and flowing blood, cut and crushed’ to be reminded by the Buddha that he was merely reaping the effects of his own kamma.

One day as he went on his round for alms he saw a woman in travail. Moved by compassion, he reported this pathetic woman’s suffering to the Buddha. He then advised him to pronounce the following words of truth, which later came to be known as the Aṇgulimāla Paritta. 193

“Sister, since my birth in the ariya clan (i.e., since his ordination) I know not that I consciously destroyed the life of any living being. By this truth may you be whole, and may your child be whole.” 194

He studied this paritta and, going to the presence of the suffering sister, sat on a seat separated from her by a screen, and uttered these words. Instantly she was delivered of the child with ease. The efficacy of this paritta persists to this day.

In due course Venerable Aṇgulimāla attained arahantship.

Referring to his memorable conversion by the Buddha, he says:

“Some creatures are subdued by force,

Some by the hook, and some by whips,

But I by such a One was tamed,

Who needed neither staff nor sword.” 195

The Buddha spent the remaining twenty-five years of his life mostly in Sāvatthī at the Jetavana Monastery built by Anāthapiṇḍika, the millionaire, and partly at Pubbārāma, built by Visākhā, the chief benefactress.

XIII.

The Buddha’s Daily Routine

“The Lord is awakened. He teaches the Dhamma for awakening.”

—Majjhima Nikāya

The Buddha can be considered the most energetic and the most active of all religious teachers that ever lived on earth. The whole day he was occupied with his religious activities except when he was attending to his physical needs. He was methodical and systematic in the performance of his daily duties. His inner life was one of meditation and was concerned with the experiencing of nibbānic bliss, while his outer life was one of selfless service for the moral upliftment of the world. Himself enlightened, he endeavoured his best to enlighten others and liberate them from the ills of life.

His day was divided into five parts: (i) the forenoon session, (ii) the afternoon session, (iii) the first watch, (iv) the middle watch, and (v) the last watch.

The Forenoon Session

Usually early in the morning he surveys the world with his divine eye to see whom he could help. If any person needs his spiritual assistance, uninvited he goes, often on foot, sometimes by air using his psychic powers, and converts that person to the right path.

As a rule he goes in search of the vicious and the impure, but the pure and the virtuous come in search of him.

For instance, the Buddha went of his own accord to convert the robber and murderer Aṇgulimāla and the wicked demon Áḷavaka, but pious young Visākhā, generous millionaire Anāthapiṇḍika, and intellectual Sāriputta and Moggallāna came up to him for spiritual guidance.

While rendering such spiritual service to whomsoever it is necessary, if he is not invited to partake of alms by a lay supporter at some particular place, he, before whom kings prostrated themselves, would go in quest of alms through alleys and streets, with bowl in hand, either alone or with his disciples.

Standing silently at the door of each house, without uttering a word, he collects whatever food is offered and placed in the bowl and returns to the monastery.

Even in his eightieth year when he was old and in indifferent health, he went on his rounds for alms in Vesāli.

Before midday he finishes his meal. Immediately after lunch he daily delivers a short discourse to the people, establishes them in the three refuges and the five precepts and if any person is spiritually advanced, he is shown the path to sainthood.

At times he grants ordination to them if they seek admission to the order and then retires to his chamber.

The Afternoon Session

After the noon meal he takes a seat in the monastery and the bhikkhus assemble to listen to his exposition of the Dhamma. Some approach him to receive suitable objects of meditation according to their temperaments; others pay their due respects to him and retire to their cells to spend the afternoon.

After his discourse or exhortation to his disciples, he himself retires to his private perfumed chamber to rest. If he so desires, he lies on his right side and sleeps for a while with mindfulness. On rising, he attains to the ecstasy of great compassion (mahā-karuṇā-samāpatti) and surveys, with his divine eye, the world, especially the bhikkhus who retired to solitude for meditation and other disciples in order to give them any spiritual advice that is needed. If the erring ones who need advice happen to be at a distance, there he goes by psychic powers, admonishes them and retires to his chamber.

Towards evening the lay followers flock to him to hear the Dhamma. Perceiving their innate tendencies and their temperaments with the buddha-eye, 196 he preaches to them for about one hour. Each member of the audience, though differently constituted, thinks that the Buddha’s sermon is directed in particular to him. Such was the Buddha’s method of expounding the Dhamma. As a rule the Buddha converts others by explaining his teachings with homely illustrations and parables, for he appeals more to the intellect than to emotion.

To the average man the Buddha at first speaks of generosity, discipline, and heavenly bliss. To the more advanced he speaks on the evils of material pleasures and on the blessings of renunciation. To the highly advanced he expounds the four noble truths.

On rare occasions as in the case of Aṇgulimāla and Khemā did the Buddha resort to his psychic powers to effect a change of heart in his listeners.

The sublime teachings of the Buddha appealed to both the masses and the intelligentsia alike. A Buddhist poet sings:

“Giving joy to the wise, promoting the intelligence of the middling, and dispelling the darkness of the dull-witted, this speech is for all people.” 197

Both the rich and the poor, the high and the low, renounced their former faiths and embraced the new message of peace. The infant sāsana (dispensation of the Buddha), which was inaugurated with a nucleus of five ascetics, soon developed into millions and peacefully spread throughout central India.

The First Watch

This period of the night extends from 6 to 10 p.m. and was exclusively reserved for instruction to bhikkhus. During this time the bhikkhus were free to approach the Buddha and get their doubts cleared, question him on the intricacies of the Dhamma, obtain suitable objects of meditation, and hear the doctrine.

The Middle Watch

During this period, which extends from 10 p.m. to 2 a.m., celestial beings such as devas and brahmas, who are invisible to the physical eye, approach the Buddha to question him on the Dhamma. An oft-recurring passage in the suttas is: “Now when the night was far spent a certain deva of surpassing splendour came to the Buddha, respectfully saluted him and stood at one side.” Several discourses and answers given to their queries appear in the Saṃyutta Nikāya.

The Last Watch

The small hours of the morning, extending from 2 to 6 a.m., which comprise the last watch, are divided into four parts.

The first part is spent in pacing up and down (caṇkamana). This serves as a mild physical exercise to him. During the second part, that is from 3 to 4 a.m. He mindfully sleeps on his right side. During the third part, that is from 4 to 5 a.m., he attains the state of arahantship and experiences nibbānic bliss. For one full hour from 5 to 6 a.m. He attains the ecstasy of great compassion (mahā-karuṇā-samāpatti) and radiates thoughts of loving kindness towards all beings and softens their hearts. At this early hour he surveys the whole world with his buddha-eye to see whether he could be of service to any. The virtuous and those that need his help appear vividly before him though they may live at a remote distance. Out of compassion for them he goes of his own accord and renders necessary spiritual assistance.

The whole day he is fully occupied with his religious duties. Unlike any other living being he sleeps only for one hour at night. For two full hours in the morning and at dawn he pervades the whole world with thoughts of boundless love and brings happiness to millions. Leading a life of voluntary poverty, seeking his alms without inconveniencing any, wandering from place to place for eight months throughout the year preaching his sublime Dhamma, he tirelessly worked for the good and happiness of all till his eightieth year.

According to the Dharmapradīpikā the last watch is divided into these four parts. According to the commentaries the last watch consists of three parts. During the third part the Buddha attains the ecstasy of great compassion.

XIV.

The Buddha’s Parinibbāna (Death)

“The sun shines by day. The moon is radiant by night.

Armoured shines the warrior king.

Meditating the brāhmaṇa shines.

But all day and night the Buddha shines in glory.”—Dhp 387

The Buddha was an extraordinary being. Nevertheless he was mortal, subject to disease and decay as are all beings. He was conscious that he would pass away in his eightieth year. Modest as he was he decided to breathe his last not in renowned cities like Sāvatthī or Rājagaha, where his activities were centred, but in a distant and insignificant hamlet like Kusinārā.

In his own words the Buddha was in his eightieth year like “a worn-out cart.” Though old in age, yet, being strong in will, he preferred to traverse the long and tardy way on foot accompanied by his favourite disciple, Venerable Ánanda. It may be mentioned that Venerable Sāriputta and Moggallāna, his two chief disciples, predeceased him. So did Venerable Rāhula and Yasodharā.

Rājagaha, the capital of Magadha, was the starting point of his last journey.

Before his impending departure from Rājagaha King Ajātasattu, the parricide, contemplating an unwarranted attack on the prosperous Vajjian Republic, sent his Prime Minister to the Buddha to know the Buddha’s view about his wicked project.

Conditions of welfare

The Buddha declared that (i) as long as the Vajjians meet frequently and hold many meetings; (2) as long as they meet together in unity, rise in unity and perform their duties in unity; (3) as long as they enact nothing not enacted, abrogate nothing that has already been enacted, act in accordance with the already established ancient Vajjian principles; (4) as long as they support, respect, venerate and honour the Vajjian elders, and pay regard to their worthy speech; (5) as long as no women or girls of their families are detained by force or abduction; (6) as long as they support, respect, venerate, honour those objects of worship—internal and external—and do not neglect those righteous ceremonies held before; (7) as long as the rightful protection, defence and support for the arahants shall be provided by the Vajjians so that arahants who have not come may enter the realm and those who have entered the realm may live in peace—so long may the Vajjians be expected not to decline, but to prosper.

Hearing these seven conditions of welfare which the Buddha himself taught the Vajjians, the Prime Minister, Vassakāra, took leave of the Buddha, fully convinced that the Vajjians could not be overcome by the king of Magadha in battle, without diplomacy or breaking up their alliance.

The Buddha thereupon availed himself of this opportunity to teach seven similar conditions of welfare mainly for the benefit of his disciples. He summoned all the bhikkhus in Rājagaha and said:

(1) “As long, O disciples, as the bhikkhus assemble frequently and hold frequent meetings; (2) as long as the bhikkhus meet together in unity, rise in unity, and perform the duties of the Sangha in unity; (3) as long as the bhikkhus shall promulgate nothing that has not been promulgated, abrogate not what has been promulgated, and act in accordance with the already prescribed rules; (4) as long as the bhikkhus support, respect, venerate and honour those long-ordained Theras of experience, the fathers and leaders of the order, and respect their worthy speech; (5) as long as the bhikkhus fall not under the influence of uprisen attachment that leads to repeated births; (6) as long as the bhikkhus shall delight in forest retreats; (7) as long as the bhikkhus develop mindfulness within themselves so that disciplined co-celibates who have not come yet may do so and those who are already present may live in peace—so long may the bhikkhus be expected not to decline, but to prosper.

As long as these seven conditions of welfare shall continue to exist amongst the bhikkhus, as long as the bhikkhus are well-instructed in these conditions—so long may they be expected not to decline, but to prosper.

With boundless compassion the Buddha enlightened the bhikkhus on seven other conditions of welfare as follows:

“As long as the bhikkhus shall not be fond of, or delight in, or engage in, business; as long as the bhikkhus shall not be fond of, or delight in, or engage in, gossiping; as long as the bhikkhus shall not be fond of, or delight in sleeping; as long as the bhikkhus shall not be fond of, or delight in, or indulge in, society; as long as the bhikkhus shall neither have, nor fall under, the influence of base desires; as long as the bhikkhus shall not have evil friends or associates and shall not be prone to evil—so long the bhikkhus shall not stop at mere lesser, special acquisition without attaining arahantship.”

Furthermore, the Buddha added that as long as the bhikkhus shall be devout, modest, conscientious, full of learning, persistently energetic, constantly mindful and full of wisdom—so long may the bhikkhus be expected not to decline, but to prosper.

Sāriputta’s Praise

Enlightening the bhikkhus with several other discourses, the Buddha, accompanied by Venerable Ánanda, left Rājagaha and went to Ambalahikā and thence to Nālandā, where he stayed at the Pāvārika mango grove. On this occasion the Venerable Sāriputta approached the Buddha and extolled the wisdom of the Buddha, saying: “Lord, so pleased am I with the Exalted One that methinks there never was, nor will there be, nor is there now, any other ascetic or brahmin who is greater and wiser than the Buddha as regards self enlightenment.”

The Buddha, who did not approve of such an encomium from a disciple of his, reminded Venerable Sāriputta that he had burst into such a song of ecstasy without fully appreciating the merits of the Buddhas of the past and of the future.

Venerable Sāriputta acknowledged that he had no intimate knowledge of all the supremely Enlightened Ones, but maintained that he was acquainted with the Dhamma lineage, the process through which all attain supreme buddhahood, that is by overcoming the five nīvaraṇa namely, (i) sense-desires, (ii) ill will, (iii) sloth and torpor, (iv) restlessness and brooding, (v) indecision; by weakening the strong passions of the heart through wisdom; by thoroughly establishing the mind in the four kinds of mindfulness; and by rightly developing the seven factors of enlightenment.

Pāliputta

From Nālandā the Buddha proceeded to Pāligāma where Sunīdha and Vassakāra, the chief ministers of Magadha, were building a fortress to repel the powerful Vajjians.

Here the Buddha resided in an empty house and, perceiving with his supernormal vision thousands of deities haunting the different sites, predicted that Pāliputta would become the chief city inasmuch as it is a residence for ariyas, a trading centre and a place for the interchange of all kinds of wares, but would be subject to three dangers arising from fire, water and dissension.

Hearing of the Buddha’s arrival at Pāligāma, the ministers invited the Buddha and his disciples for a meal at their house. After the meal was over the Buddha exhorted them in these verses:

“Wheresoe’er the prudent man shall take up his abode.

Let him support the brethren there, good men of self-control,

And give the merit of his gifts to the deities

who haunt the spot.

Revered, they will revere him: honoured,

they honour him again,

Are gracious to him as a mother to her own, her only son.

And the man who has the grace of the gods,

good fortune he beholds.” 198

In honour of his visit to the city they named the gate by which he left “Gotama-Gate”, and they desired to name the ferry by which he would cross “Gotama-Ferry,” but the Buddha crossed the overflowing Ganges by his psychic powers while the people were busy making preparations to cross.

Future states

From the banks of the Ganges he went to Kotigama and thence to the village of Nadika and stayed at the Brick Hall. Thereupon the Venerable Ánanda approached the Buddha and respectfully questioned him about the future states of several persons who died in that village. The Buddha patiently revealed the destinies of the persons concerned and taught how to acquire the mirror of the Dhamma so that an ariya disciple endowed therewith may predict of himself thus: “Destroyed for me is birth in a woeful state, animal realm, Peta 199 realm, sorrowful, evil, and low states. A stream-winner am I, not subject to fall, assured of final enlightenment.”

The Mirror of the Dhamma (Dhammādāsa)

Then the Buddha explained the mirror of the Dhamma as follows:

“What, O Ánanda, is the mirror of the Dhamma?

“Herein a noble disciple reposes perfect confidence in the Buddha reflecting on his virtues thus:

“‘Thus, indeed, is the Exalted One, a Worthy One, a Fully Enlightened One, Endowed with wisdom and conduct, an Accomplished One, Knower of the worlds, an Incomparable Charioteer for the training of individuals, the Teacher of gods and men, Omniscient, and Holy.’ 200

“He reposes perfect confidence in the Dhamma reflecting on the characteristics of the Dhamma thus:

“‘Well expounded is the Dhamma by the Exalted One, to be self-realised, immediately effective, inviting investigation, leading onwards (to Nibbāna), to be understood by the wise, each one for himself.’ 201

“He reposes perfect confidence in the Sangha reflecting on the virtues of the Sangha thus:

“‘Of good conduct is the order of the disciples of the Exalted One; of upright conduct is the order of the disciples of the Exalted One; of right conduct is the order of the disciples of the Exalted One; of proper conduct is the order of the disciples of the Exalted One. These four pairs of persons constitute eight individuals. This order of the disciples of the Exalted One is worthy of gifts, of hospitality, of offerings, of reverence, is an incomparable field of merit to the world.’ 202

“He becomes endowed with virtuous conduct pleasing to the ariyas, unbroken, intact, unspotted, unblemished, free, praised by the wise, untarnished by desires, conducive to concentration.”

From Nadika the Buddha went to the flourishing city of Vesāli and stayed at the grove of Ambapāli, the beautiful courtesan.

Anticipating her visit, the Buddha in order to safeguard his disciples, advised them to be mindful and reflective and taught them the way of mindfulness.

Ambapāli

Ambapāli, hearing of the Buddha’s arrival at her mango grove, approached the Buddha and respectfully invited him and his disciples for a meal on the following day. The Buddha accepted her invitation in preference to the invitation of the Licchavi nobles which he received later. Although the Licchavi nobles offered a large sum of money to obtain from her the opportunity of providing this meal to the Buddha, she politely declined this offer. As invited, the Buddha had his meal at Ambapāli’s residence. After the meal Ambapāli, the courtesan, who was a potential arahant, very generously offered her spacious mango grove to the Buddha and his disciples. 203

As it was the rainy season the Buddha advised his disciples to spend their retreat in or around Vesāli, and he himself decided to spend the retreat, which was his last and forty-fifth one, at Beluva, a village near Vesāli.

The Buddha’s Illness

In this year he had to suffer from a severe sickness, and “sharp pains came upon him even unto death.” With his iron will, mindful and reflective, the Buddha bore them without any complaint.

The Buddha was now conscious that he would soon pass away. But he thought that it would not be proper to pass away without addressing his attendant disciples and giving instructions to the order. So he decided to subdue his sickness by his will and live by constantly experiencing the bliss of arahantship.

Immediately after recovery, the Venerable Ánanda approached the Buddha, and expressing his pleasure on his recovery, remarked that he took some little comfort from the thought that the Buddha would not pass away without any instruction about the order.

The Buddha made a memorable and significant reply which clearly reveals the unique attitude of the Buddha, Dhamma, and the Sangha.

The Buddha’s Exhortation

“What, O Ánanda, does the order of disciples expect of me? I have taught the Dhamma making no distinction between esoteric and exoteric doctrine. 204 In respect of the truths the Tathāgata has no closed fist of a teacher. It may occur to anyone: ‘It is I who will lead the order of bhikkhus,’ or ‘The order of bhikkhus is dependent upon me,’ or ‘It is he who should instruct any matter concerning the order.’

“The Tathāgata, Ánanda, thinks not that it is he who should lead the order of bhikkhus, or that the order is dependent upon him. Why then should he leave instructions in any matter concerning the order?

“I, too, Ánanda, am now decrepit, aged, old, advanced in years, and have reached my end. I am in my eightieth year. Just as a worn-out cart is made to move with the aid of thongs, even so methinks the body of the Tathāgata is moved with the aid of thongs. 205 Whenever, Ánanda, the Tathāgata lives plunged in signless mental one-pointedness, by the cessation of certain feelings and unmindful of all objects, then only is the body of the Tathāgata at ease. 206

“Therefore, Ánanda, be you islands 207 unto yourselves. Be you a refuge to yourselves. Seek no external refuge. Live with the Dhamma as your island, the Dhamma as your refuge. Betake to no external refuge. 208

“How, Ánanda, does a bhikkhu live as an island unto himself, as a refuge unto himself, seeking no external refuge, with the Dhamma as an island, with the Dhamma as a refuge, seeking no external refuge?

“Herein, Ánanda, a bhikkhu lives strenuous, reflective, watchful, abandoning covetousness in this world, constantly developing mindfulness with respect to body, feelings, consciousness, and Dhamma. 209

“Whosoever shall live either now or after my death as an island unto oneself, as a refuge unto oneself, seeking no external refuge, with the Dhamma as an island, with the Dhamma as a refuge, seeking no external refuge, those bhikkhus shall be foremost amongst those who are intent on discipline.”

Here the Buddha lays special emphasis on the importance of individual striving for purification and deliverance from the ills of life. There is no efficacy in praying to others or in depending on others. One might question why Buddhists should seek refuge in the Buddha, Dhamma, and the Sangha when the Buddha had explicitly advised his followers not to seek refuge in others. In seeking refuge in the Triple Gem (Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha) Buddhists only regard the Buddha as an instructor who merely shows the path of deliverance, the Dhamma as the only way or means, the Sangha as the living examples of the way of life to be lived. By merely seeking refuge in them Buddhists do not consider that they would gain their deliverance.

Though old and feeble the Buddha not only availed himself of every opportunity to instruct the bhikkhus in various ways but also regularly went on his rounds for alms with bowl in hand when there were no private invitations. One day as usual he went in quest of alms in Vesāli and after his meal went with Venerable Ánanda to the Capala Cetiya, and, speaking of the delightfulness of Vesāli and other shrines in the city, addressed the Venerable Ánanda thus:

Whosoever has cultivated, developed, mastered, made a basis of, experienced, practised, thoroughly acquired the four means of accomplishment (iddhipāda) 210 could, if he so desires, live for an aeon (kappa) 211 or even a little more (kappāvasesa). The Tathāgata, O Ánanda, has cultivated, developed, mastered, made a basis of, experienced, practised, thoroughly acquired the four means of accomplishment. If he so desires, the Tathāgata could remain for an aeon or even a little more.

The text adds that “even though a suggestion so evident and so clear was thus given by the Exalted One, the Venerable Ánanda was incapable of comprehending it so as to invite the Buddha to remain for an aeon for the good, benefit, and the happiness of the many, out of compassion for the world, for the good, benefit, and happiness of gods and men”.

The sutta attributes the reason to the fact that the mind of Venerable Ánanda was, at the moment, dominated by Māra the evil one.

The Buddha Announces his Death

The Buddha appeared on earth to teach the seekers of truth things as they truly are and a unique path for the deliverance from all ills of life. During his long and successful ministry he fulfilled his noble mission to the satisfaction of both himself and his followers. In his eightieth year he felt that his work was over. He had given all necessary instructions to his earnest followers—both the householders and the homeless ones—and they were not only firmly established in his teachings but were also capable of expounding them to others. He therefore decided not to control the remainder of his life span by his will-power and by experiencing the bliss of arahantship. While residing at the Capala Cetiya the Buddha announced to Venerable Ánanda that he would pass away in three months’ time.

Venerable Ánanda instantly recalled the saying of the Buddha and begged of him to live for a kappa for the good and happiness of all.

“Enough Ánanda, beseech not the Tathāgata. The time for making such a request is now past,” was the Buddha’s reply.

He then spoke on the fleeting nature of life and went with Venerable Ánanda to the Pinnacled Hall at Mahāvana and requested him to assemble all the bhikkhus in the neighbourhood of Vesāli.

To the assembled bhikkhus the Buddha spoke as follows:

“Whatever truths have been expounded to you by me, study them well, practise, cultivate and develop them so that this holy life may last long and be perpetuated out of compassion for the world, for the good and happiness of the many, for the good and happiness of gods and men.”

“What are those truths? They are:

the four foundations of mindfulness,

the four kinds of right endeavour,

the four means of accomplishment,

the five faculties,

the five powers,

the seven factors of enlightenment, and

the Noble Eightfold Path.” 212

He then gave the following final exhortation and publicly announced the time of his death to the Sangha.

The Buddha’s Last Words

“Behold, O bhikkhus, now I speak to you. Transient are all conditioned things. Strive on with diligence. 213 The passing away of the Tathāgata will take place before long. At the end of three months from now the Tathāgata will pass away.

Ripe is my age. Short is my life. Leaving you I shall depart. I have made myself my refuge. O bhikkhus, be diligent, mindful and virtuous. With well-directed thoughts guard your mind. He who lives heedfully in this dispensation will escape life’s wandering and put an end to suffering. 214

Casting his last glance at Vesāli, the Buddha went with Venerable Ánanda to Bhandagāma and addressing the bhikkhus said:

Morality, concentration, wisdom, and deliverance supreme.

These things were realised by the renowned Gotama.

Comprehending them, the Buddha taught the doctrine to the

disciples.

The Teacher with sight has put an end to sorrow

and has extinguished all passions.

The Four Great References

Passing thence from village to village, the Buddha arrived at Bhoganagara and there taught the four great citations or references (mahāpadesa) by means of which the word of the Buddha could be tested and clarified in the following discourse:

(1) “A bhikkhu may say thus: ‘From the mouth of the Buddha himself have I heard, have I received thus: “This is the doctrine, this is the discipline, this is the teaching of the Master.’ His words should neither be accepted nor rejected. Without either accepting or rejecting such words, study thoroughly every word and syllable and then put them beside the discourses (sutta) and compare them with the disciplinary rules (vinaya). If, when so compared, they do not harmonise with the discourses and do not agree with the disciplinary rules, then you may come to the conclusion. ‘Certainly this is not the word of the Exalted One, this has been wrongly grasped by the bhikkhu.’

“Therefore you should reject it.

“If, when compared and contrasted, they harmonise with the discourses and agree with the disciplinary rules, you may come to the conclusion: ‘Certainly this is the word of the Exalted One, this has correctly been grasped by the bhikkhu.’

“Let this be regarded as the first great reference.

(2) “Again, a bhikkhu may say thus: ‘In such a monastery lives the Sangha together with leading theras. From the mouth of that Sangha have I heard, have I received thus: “This is the doctrine, this is the discipline, this is the Master’s teaching.”‘ His words should neither be accepted nor rejected. Without either accepting or rejecting such words, study thoroughly every word and syllable and then put them beside the discourses and compare them with the disciplinary rules. If, when so compared, they do not harmonise with the discourses and do not agree with the disciplinary rules, then you may come to the conclusion: ‘Certainly this is not the word of the Exalted One, this has been wrongly grasped by the bhikkhu.’

“Therefore you should reject it.

“If, when compared and contrasted, they harmonise with the discourses and agree with the disciplinary rules, you may come to the conclusion: ‘Certainly this is the word of the Exalted One, this has correctly been grasped by the bhikkhu.’

“Let this be regarded as the second great reference.

(3) “Again, a bhikkhu may say thus: ‘In such a monastery dwell many theras and bhikkhus of great learning, versed in the teachings, proficient in the Doctrine, Vinaya (discipline), and matrices (mātikā). From the mouth of those theras have I heard, have I received thus: “This is the Dhamma, this is the Vinaya, this is the teaching of the Master.”‘ His words should neither be accepted nor rejected. Without either accepting or rejecting such words, study thoroughly every word and syllable and then put them beside the discourses and compare them with the disciplinary rules. If, when so compared, they do not harmonise with the discourses and do not agree with the disciplinary rules, then you may come to the conclusion: ‘Certainly this is not the word of the Exalted One, this has been wrongly grasped by the bhikkhu.’

“Therefore you should reject it.

“If, when compared and contrasted, they harmonise with the Suttas and agree with the Vinaya, then you may come to the conclusion: ‘Certainly this is the word of the Exalted One, this has been correctly grasped by the bhikkhu.’

“Let this be regarded as the third great reference.

(4) “Again, a bhikkhu may say thus: ‘In such a monastery lives an elderly bhikkhu of great learning, versed in the teachings, proficient in the Dhamma, Vinaya, and Matrices. From the mouth of that thera have I heard, have I received thus: “This is the Dhamma, this is the Vinaya, this is the Master’s teaching.”‘ His words should neither be accepted nor rejected. Without either accepting or rejecting such words, study thoroughly every word and syllable and then put them beside the discourses and compare them with the disciplinary rules. If, when so compared, they do not harmonise with the discourses and do not agree with the disciplinary rules, then you may come to the conclusion: ‘Certainly this is not the word of the Exalted One, this has been wrongly grasped by the bhikkhu.’

“Therefore you should reject it.

“If, when compared and contrasted, they harmonise with the suttas and agree with the Vinaya, then you may come to the conclusion: ‘Certainly this is the Dhamma, this is the Vinaya, this is the Master’s teachings.’

“Let this be regarded as the fourth great reference.

“These, bhikkhus, are the four great references.”

The Buddha’s Last Meal

Enlightening the disciples with such edifying discourses, the Buddha proceeded to Pāva where the Buddha and his disciples were entertained by Cunda the smith. With great fervour Cunda prepared a special delicious dish called ‘sūkaramaddava’. 215 As advised by the Buddha, Cunda served only the Buddha with the sūkaramaddava and buried the remainder in the ground.

After the meal the Buddha suffered from an attack of dysentery and sharp pains came upon him. Calmly he bore them without any complaint.

Though extremely weak and severely ill, the Buddha decided to walk to Kusinārā 216 his last resting place, a distance of about three gāvutas 217 from Pāva. In the course of this last journey it is stated that the Buddha had to sit down in about twenty-five places owing to his weakness and illness.

On the way he sat at the foot of a tree and asked Venerable Ánanda to fetch some water as he was feeling thirsty. With difficulty Venerable Ánanda secured some pure water from a streamlet which, a few moments earlier, was flowing fouled and turbid, stirred up by the wheels of five hundred carts.

At that time a man named Pukkusa approached the Buddha, and expressed his admiration at the serenity of the Buddha, and, hearing a sermon about his imperturbability, offered him a pair of robes of gold.

As directed by the Buddha, he robed the Buddha with one and Venerable Ánanda with the other.

When Venerable Ánanda placed the pair of robes on the Buddha, to his astonishment, he found the skin of the Buddha exceeding bright, and said, “How wonderful a thing is it, Lord and how marvellous, that the colour of the skin of the Exalted One should be so clear, so exceeding bright. For when I placed even this pair of robes of burnished gold and ready for wear on the body of the Exalted One, it seemed as if it had lost its splendour.”

Thereupon the Buddha explained that on two occasions the colour of the skin of the Tathāgata becomes clear and exceeding bright—namely on the night on which the Tathāgata attains buddhahood and on the night the Tathāgata passes away.

He then pronounced that at the third watch of the night on that day he would pass away in the Sāla Grove of the Mallas between the twin Sāla trees, in the vicinity of Kusinārā.

Cunda’s Meritorious Meal

He took his last bath in the river Kukuttha and resting a while spoke thus—”Now it may happen, Ánanda, that some one should stir up remorse in Cunda the smith, saying: ‘This is evil to thee, Cunda, and loss to thee in that when the Tathāgata had eaten his last meal from your provisions, then he died.’ Any such remorse in Cunda the smith should be checked by saying: ‘This is good to thee, Cunda, and gain to thee, in that when the Tathāgata had eaten his last meal from your provision, then he died.’ From the very mouth of the Exalted One, Cunda, have I heard, from his very mouth have I received this saying: “These two offerings of food are of equal fruit, and of equal profit, and of much greater fruit and of much greater profit than any other, and which are the two?

“The offering of food which when a Tathāgata has eaten he attains to supreme and perfect insight, and the offering of food which when a Tathāgata has eaten he passes away by that utter cessation in which nothing whatever remains behind—these two offerings of food are of equal fruit and of equal profit, and of much greater fruit, and of much greater profit than any other.

“There has been laid up by Cunda the smith a kamma redounding to length of life, redounding to good birth, redounding to good fortune, redounding to good fame, redounding to the inheritance of heaven and of sovereign power.

“In this way, Ánanda, should be checked any remorse in Cunda the smith.”

Uttering these words of consolation out of compassion to the generous donor of his last meal, he went to the Sāla Grove of the Mallas and asked Venerable Ánanda to prepare a couch with the head to the north between the twin Sāla trees. The Buddha laid himself down on his right side with one leg resting on the other, mindful and self-possessed.

How the Buddha is Honoured

Seeing the Sāla trees blooming with flowers out of season, and other outward demonstrations of piety, the Buddha exhorted his disciples thus:

It is not thus, Ánanda, that the Tathāgata is respected, reverenced, venerated, honoured, and revered. Whatever bhikkhu or bhikkhuṇī, upāsaka or upāsika lives in accordance with the teaching, conducts himself dutifully, and acts righteously, it is he who respects, reverences, venerates, honours, and reveres the Tathāgata with the highest homage. Therefore, Ánanda, should you train yourselves thus: ‘Let us live in accordance with the teaching, dutifully conducting ourselves, and acting righteously.’

At this moment the Venerable Upavāna, who was once attendant of the Buddha, was standing in front of the Buddha fanning him. The Buddha asked him to stand aside.

Venerable Ánanda wished to know why he was asked to stand aside as he was very serviceable to the Buddha.

The Buddha replied that devas had assembled in large numbers to see the Tathāgata and they were displeased because he was standing in their way concealing him.

The Four Sacred Places

The Buddha then spoke of four places, made sacred by his association, which faithful followers should visit with reverence and awe. They are:

The birthplace of the Buddha, 218

The place where the Buddha attained enlightenment, 219

The place where the Buddha established the incomparable wheel of truth 220 (dhammacakka), and

The place where the Buddha attained parinibbāna. 221

“And they,” added the Buddha, “who shall die with a believing heart, in the course of their pilgrimage, will be reborn, on the dissolution of their body, after death, in a heavenly state.”

Conversion of Subhadda

At that time a wandering ascetic, named Subhadda, 222 was living at Kusinārā. He heard the news that the Ascetic Gotama would attain parinibbāna in the last watch of the night. And he thought, “I have heard grown-up and elderly teachers, and their teachers, the wandering ascetics, say that seldom and very seldom, indeed, do exalted, fully enlightened arahants arise in this world. Tonight in the last watch the Ascetic Gotama will attain parinibbāna. A doubt has arisen in me, and I have confidence in the Ascetic Gotama. Capable, indeed, is the Ascetic Gotama to teach the doctrine so that I may dispel my doubt.