XXI.

Nature of Kamma

“As you sow the seed so shall you reap the fruit.”

— Saṃyutta Nikāya

Is one bound to reap all that one has sown in just proportion?

Not necessarily! In the Aṇguttara Nikāya the Buddha states:

“If any one says that a man must reap according to his deeds, in that case there is no religious life nor is an opportunity afforded for the entire extinction of sorrow. But if any one says that what a man reaps accords with his deeds, in that case there is a religious life and an opportunity is afforded for the entire extinction of sorrow.” 315

In Buddhism therefore there is every possibility to mould one’s kamma.

Although it is stated in the Dhammapada (v. 127) that “not in the sky, nor in mid-ocean nor entering a mountain cave is found that place on earth, where abiding one may escape from [the consequence of] an evil deed,” yet one is not bound to pay all the arrears of past kamma. If such were the case, emancipation would be an impossibility. Eternal suffering would be the unfortunate result.

One is neither the master nor the servant of this kamma. Even the most vicious person can by his own effort become the most virtuous person. We are always becoming something and that something depends on our own actions. We may at any moment change for the better or for the worse. Even the most wicked person should not be discouraged or despised on account of his evil nature. He should be pitied, for those who censure him may also have been in that same position at a certain stage. As they have changed for the better he may also change, perhaps sooner than they.

Who knows what good kamma he has in store for him? Who knows his potential goodness?

Aṇgulimāla, a highway robber and the murderer of more than a thousand of his brethren became an arahant and erased, so to speak, all his past misdeeds.

Áḷavaka, the fierce demon who feasted on the flesh of human beings, gave up his carnivorous habits and attained the first stage of sainthood.

Ambapāli, a courtesan, purified her character and attained arahantship. Asoka, who was stigmatised as Canda (wicked), owing to his ruthlessness in expanding his empire, became Dharmāsoka, or Asoka the Righteous, and changed his career to such an extent that today “Amidst the tens of thousands of names of monarchs that crowd the columns of history, their majesties and graciousnesses, serenities, royal highnesses and the like the name of Asoka shines, and shines almost alone, a star.” 316

These are a few striking examples which serve to show how a complete reformation of character can be effected by sheer determination.

It may so happen that in some cases a lesser evil may produce its due effect, while the effect of a greater evil may be minimised.

The Buddha says:

“Here, O bhikkhus, a certain person is not disciplined in body, in morality, in mind, in wisdom, has little good and less virtue, and lives painfully in consequence of trifling misdeeds. Even a trivial act committed by such a person will lead him to a state of misery.

“Here, O bhikkhus, a certain person is disciplined in body, in morality, in mind, in wisdom, does much good, is high-souled and lives with boundless compassion towards all.

“A similar evil committed by such a person ripens in this life itself and not even a small effect manifests itself (after death), not to say a great one.317

“It is as if a man were to put a lump of salt into a small cup of water. What do you think, O bhikkhus? Would now the small amount of water in this cup become salty and undrinkable?”

“Yes, Lord.”

“And why?”

“Because, Lord, there was very little water in the cup, and so it became salty and undrinkable by this lump of salt.

“Suppose a man were to put a lump of salt into the river Ganges. What think you, O bhikkhus? Would now the river Ganges become salty and undrinkable by the lump of salt?

“Nay, indeed, Lord.”

“And why not?”

“Because, Lord, the mass of water in the river Ganges is great, and so it would not become salty and undrinkable.”

“In exactly the same way we may have the case of a person who does some slight evil deed which brings him to a state of misery, or, again, we may have the case of another person who does the same trivial misdeed, yet he expiates it in his present life. Not even a small effect manifests itself (after death), not to say a great one.

“We may have the case of a person who is cast into prison for the theft of a half-penny, penny, or for a hundred pence or, again, we may have the case of a person who is not cast into prison for a half-penny, for a penny, for a hundred pence.

“Who is cast into prison for a half-penny, for a penny, or for a hundred pence? Whenever any one is poor, needy and indigent, he is cast into prison for a half-penny, for a penny, or for a hundred pence.

“Who is not cast into prison for a half-penny, or for a penny, or for a hundred pence?

“Whenever any one is rich, wealthy, and affluent, he is not cast into prison for a half-penny, for a penny, for a hundred pence.

“In exactly the same way we may have the case of a person who does some slight evil deed which brings him to a state of misery, or again we may have the case of another person who does the same trivial misdeed, and expiates it in the present life. Not even a small effect manifests itself (after death), not to say a great one.” 318

Cause of Adverse Results

Good begets good, but any subsequent regrets on the part of the doer in respect of the good done, deprive him of the due desirable results.

The following case may be cited in illustration:

On one occasion King Pasenadi of Kosala approached the Buddha and said:

“Lord, here in Sāvatthī a millionaire householder has died. He has left no son behind him, and now I come here, after having conveyed his property to the palace. Lord, a hundred lakhs in gold, to say nothing of the silver. But this millionaire householder used to eat broken scraps of food and sour gruel. And how did he clothe himself? For dress he wore a robe of coarse hemp, and as to his coach, he drove in a broken-down cart rigged up with a leaf-awning.”

Thereupon the Buddha said:

“Even so, O King, even so. In a former life, O King, this millionaire householder gave alms of food to a paccekabuddha called Tagarasikhi. Later, he repented of having given the food, saying within himself: ‘It would be better if my servants and workmen ate the food I gave for alms.’ And besides this he deprived his brother’s only son of his life for the sake of his property. And because this millionaire householder gave alms of food to the paccekabuddha Tagarasikhi, in requital for this deed, he was reborn seven times in heavenly blissful states. And by the residual result of that same action, he became seven times a millionaire in this very Sāvatthī.

“And because this millionaire householder repented of having given alms, saying to himself: ‘It would be better if my servants and workmen ate the food.’ Therefore as a requital for this deed, he had no appreciation of good food, no appreciation of fine dresses, no appreciation of an elegant vehicle, no appreciation of the enjoyments of the five senses.

“And because this millionaire householder slew the only son of his brother for the sake of his property, as requital for this deed, he had to suffer many years, many hundreds of years, many thousands of years, many hundreds of thousand of years of pain in states of misery. And by the residual of that same action, he is without a son for the seventh time, and in consequence of this, had to leave his property to the royal treasury.” 319

This millionaire obtained his vast fortune as a result of the good act done in a past birth, but since he repented of his good deed, he could not fully enjoy the benefit of the riches which kamma provided him.

Beneficent and Maleficent Forces

In the working of kamma it should be understood that there are beneficent and maleficent forces to counteract and support this self-operating law. Birth (gati), time or conditions (kāla), personality or appearance (upadhi) and effort (payoga) are such aids and hindrances to the fruition of kamma.

If, for instance, a person is born in a noble family or in a state of happiness, his fortunate birth will sometimes hinder the fruition of his evil kamma.

If, on the other hand, he is born in a state of misery or in an unfortunate family, his unfavourable birth will provide an easy opportunity for his evil kamma to operate.

This is technically known as gati sampatti (favourable birth) and gati vipatti (unfavourable birth).

An unintelligent person, who, by some good kamma, is born in a royal family, will, on account of his noble parentage, be honoured by the people. If the same person were to have a less fortunate birth, he would not be similarly treated.

King Dutthagamani of Sri Lanka, for instance, acquired evil kamma by waging war with the Tamils, and good kamma by his various religious and social deeds. Owing to his good reproductive kamma he was born in a heavenly blissful state. Tradition says that he will have his last birth in the time of the future Buddha Metteyya. His evil kamma cannot, therefore, successfully operate owing to his favourable birth.

To cite another example, King Ajātasattu, who committed parricide, became distinguished for his piety and devotion later owing to his association with the Buddha. He now suffers in a woeful state as a result of his heinous crime. His unfavourable birth would not therefore permit him to enjoy the benefits of his good deeds.

Beauty (upadhi sampatti), and ugliness (upadhi vipatti) are two other factors that hinder and favour the working of kamma.

If, by some good kamma, a person obtains a happy birth but unfortunately is deformed, he will not be able fully to enjoy the beneficial results of his good kamma. Even a legitimate heir to the throne may not perhaps be raised to that exalted position if he happens to be physically deformed. Beauty, on the other hand, will be an asset to the possessor. A good-looking son of a poor parent may attract the attention of others and may be able to distinguish himself through their influence.

Favourable time or occasion and unfavourable time or occasion (kalā sampatti and kalā vipatti) are two other factors that effect the working of kamma; the one aids, and the other impedes the working of kamma.

In the case of a famine all without exception will be compelled to suffer the same fate. Here the unfavourable conditions open up possibilities for evil kamma to operate. The favourable conditions, on the other hand, will prevent the operation of evil kamma.

Of these beneficent and maleficent forces the most important is effort (payoga). In the working of kamma effort or lack of effort plays a great part. By present effort one can create fresh kamma, new surroundings, new environment, and even a new world. Though placed in the most favourable circumstances and provided with all facilities, if one makes no strenuous effort, one not only misses golden opportunities but may also ruin oneself. Personal effort is essential for both worldly and spiritual progress.

If a person makes no effort to cure himself of a disease or to save himself from his difficulties, or to strive with diligence for his progress, his evil kamma will find a suitable opportunity to produce its due effects. If, on the contrary, he endeavours on his part to surmount his difficulties, to better his circumstances, to make the best use of the rare opportunities, to strive strenuously for his real progress, his good kamma will come to his succour.

When ship-wrecked in deep sea, the Bodhisatta Mahā Jānaka made a great effort to save himself, while the others prayed to the gods and left their fate in their hands. The result was that the Bodhisatta escaped while the others were drowned.

These two important factors are technically known as payoga sampatti and payoga vipatti.

Though we are neither absolutely the servants nor the masters of our kamma, it is evident from these counteractive and supportive factors that the fruition of kamma is influenced to some extent by external circumstances, surroundings, personality, individual striving, and the like.

It is this doctrine of kamma that gives consolation, hope, reliance, and moral courage to a Buddhist.

When the unexpected happens, difficulties, failures, and misfortunes confront him, the Buddhist realises that he is reaping what he has sown, and is wiping off a past debt. Instead of resigning himself, leaving everything to kamma, he makes a strenuous effort to pull out the weeds and sow useful seeds in their place for the future is in his hands.

He who believes in kamma, does not condemn even the most corrupt, for they have their chance to reform themselves at any moment. Though bound to suffer in woeful states, they have the hope of attaining eternal peace. By their deeds they create their own hells, and by their own deeds they can also create their own heavens.

A Buddhist who is fully convinced of the law of kamma does not pray to another to be saved but confidently relies on himself for his emancipation. Instead of making any self-surrender, or propitiating any supernatural agency, he would rely on his own will-power and work incessantly for the weal and happiness of all.

This belief in kamma, “validates his effort and kindles his enthusiasm,” because it teaches individual responsibility.

To an ordinary Buddhist kamma serves as a deterrent, while to an intellectual it serves as an incentive to do good.

This law of kamma explains the problem of suffering, the mystery of the so-called fate and predestination of some religions, and above all the inequality of mankind.

We are the architects of our own fate. We are our own creators. We are our own destroyers. We build our own heavens. We build our own hells.

What we think, speak and do, become our own. It is these thoughts, words, and deeds that assume the name of kamma and pass from life to life exalting and degrading us in the course of our wanderings in saṃsāra.

Says the Buddha,

Man’s merits and the sins he here hath wrought:

That is the thing he owns, that takes he hence,

That dogs his steps, like shadows in pursuit.

Hence let him make good store for life elsewhere.

Sure platform in some other future world,

Rewards of Virtue on good beings wait.—Kindred Sayings, i. p. 98

XXII.

What is the Origin of Life?

“Inconceivable is the beginning, O disciples, of this faring on. The earliest point is not revealed of the running on, the faring on, of beings, cloaked in ignorance, tied by craving.”

—Saṃyutta Nikāya

Rebirth, which Buddhists do not regard as a mere theory but as a fact verifiable by evidence, forms a fundamental tenet of Buddhism, though its goal Nibbāna is attainable in this life itself. The bodhisatta ideal and the correlative doctrine of freedom to attain utter perfection are based on this doctrine of rebirth.

Documents record that this belief in rebirth, viewed as transmigration or reincarnation, was accepted by philosophers like Pythagoras and Plato, poets like Shelly, Tennyson and Wordsworth, and many ordinary people in the East as well as in the West.

The Buddhist doctrine of rebirth should be differentiated from the theory of transmigration and reincarnation of other systems, because Buddhism denies the existence of a transmigrating permanent soul, created by God, or emanating from a paramātma (divine essence).

It is kamma that conditions rebirth. Past kamma conditions the present birth; and present kamma, in combination with past kamma, conditions the future. The present is the offspring of the past, and becomes, in turn, the parent of the future.

The actuality of the present needs no proof as it is self-evident. That of the past is based on memory and report, and that of the future on forethought and inference.

If we postulate a past, a present and a future life, then we are at once faced with the problem “What is the ultimate origin of life?”

One school, in attempting to solve the problem, postulates a first cause, whether as a cosmic force or as an Almighty Being. Another school denies a first cause for, in common experience, the cause ever becomes the effect and the effect becomes the cause. In a circle of cause and effect a first cause 320 is inconceivable. According to the former, life has had a beginning, according to the latter, it is beginningless. In the opinion of some the conception of a first cause is as ridiculous as a round triangle.

One might argue that life must have had a beginning in the infinite past and that beginning or the first cause is the creator.

In that case there is no reason why the same demand may not be made of this postulated creator.

With respect to this alleged first cause men have held widely different views. In interpreting this first cause, Paramātma, Brahmā, Isvara, Jehovah, God, the Almighty, Allah, Supreme Being, Father in Heaven, creator, order of Heaven, Prime Mover, Uncaused Cause, Divine Essence, Chance, Pakati, Padhāna are some significant terms employed by certain religious teachers and philosophers.

Hinduism traces the origin of life to a mystical Paramātma from which emanate all Átmas or souls that transmigrate from existence to existence until they are finally reabsorbed in Paramātma. One might question whether there is any possibility for these reabsorbed Átmas for a further transmigration.

Christianity, admitting the possibility of an ultimate origin, attributes everything to the fiat of an Almighty God. As Schopenhauer says,

“Whoever regards himself as having come out of nothing must also think that he will again become nothing, for that an eternity has passed before he was, and then a second eternity had begun, through which he will never cease to be, is a monstrous thought.

“Moreover, if birth is the absolute beginning, then death must be the absolute end; and the assumption that man is made out of nothing, leads necessarily to the assumption that death is his absolute end.” 321

Argues Spencer Lewis:

“According to the theological principles, man is created arbitrarily and without his desire, and at the moment of creation is either blessed or unfortunate, noble or depraved, from the first step in the process of his physical creation to the moment of his last breath, regardless of his individual desires, hopes, ambitions, struggles or devoted prayers. Such is theological fatalism.

“The doctrine that all men are sinners and have the essential sin of Adam is a challenge to justice, mercy, love and omnipotent fairness.”

Huxley says:

“If we are to assume that anybody has designedly set this wonderful universe going, it is perfectly clear to me that he is no more entirely benevolent and just, in any intelligible sense of the words, than that he is malevolent and unjust.”

According to Einstein:

“If this being (God) is omnipotent, then every occurrence, including every human action, every human thought, and every human feeling and aspiration is also his work; how is it possible to think of holding men responsible for their deeds and thoughts before such an Almighty Being?

“In giving out punishments and rewards, he would to a certain extent be passing judgment on himself. How can this be combined with the goodness and righteousness ascribed to him?”

According to Charles Bradlaugh:

“The existence of evil is a terrible stumbling block to the Theist. Pain, misery, crime, poverty confront the advocate of eternal goodness, and challenge with unanswerable potency his declaration of Deity as all-good, all-wise, and all-powerful.”

Commenting on human suffering and God, Prof. J. B. S. Haldane writes:

“Either suffering is needed to perfect human character, or God is not Almighty. The former theory is disproved by the fact that some people who have suffered very little but have been fortunate in their ancestry and education have very fine characters. The objection to the second is that it is only in connection with the universe as a whole that there is any intellectual gap to be filled by the postulation of a deity. And a creator could presumably create whatever he or it wanted.” 322

In “Despair, a poem of his old age, Lord Tennyson thus boldly attacks God, who, as recorded in Isaiah, says, “I make peace and create evil.” 323

“What! I should call on that infinite Love

that has served us so well?

Infinite cruelty, rather, that made everlasting hell.

Made us, foreknew us, foredoomed us,

and does what he will with his own.

Better our dead brute mother

who never has heard us groan.”

Dogmatic writers of old authoritatively declared that God created man after his own image. Some modern thinkers state, on the contrary, that man created God after his own image. 324 With the growth of civilisation man’s conception of God grows more and more refined. There is at present a tendency to substitute this personal God by an impersonal God.

Voltaire states that God is the noblest creation of man.

It is however impossible to conceive of such an omnipotent, omnipresent being, an epitome of everything that is good—either in or outside the universe.

Modern science endeavours to tackle the problem with its limited systematised knowledge. According to the scientific standpoint, we are the direct products of the sperm and ovum cells provided by our parents. But science does not give a satisfactory explanation with regard to the development of the mind, which is infinitely more important than the machinery of man’s material body. Scientists, while asserting “omne vivum ex vivo” “all life from life” maintain that mind and life evolved from the lifeless.

Now from the scientific standpoint we are absolutely parent-born. Thus our lives are necessarily preceded by those of our parents and so on. In this way life is preceded by life until one goes back to the first protoplasm or colloid. As regards the origin of this first protoplasm or colloid, however, scientists plead ignorance.

What is the attitude of Buddhism with regard to the origin of life?

At the outset it should be stated that the Buddha does not attempt to solve all the ethical and philosophical problems that perplex mankind. Nor does he deal with speculations and theories that tend neither to edification nor to enlightenment. Nor does he demand blind faith from his adherents in a first cause. He is chiefly concerned with one practical and specific problem—that of suffering and its destruction, all side issues are completely ignored.

On one occasion a bhikkhu named Māluṇkyaputta, not content to lead the holy life, and achieve his emancipation by degrees, approached the Buddha and impatiently demanded an immediate solution of some speculative problems with the threat of discarding the robes if no satisfactory answer was given. He said,

“Lord, these theories have not been elucidated, have been set aside and rejected by the Blessed One—whether the world is eternal or not eternal, whether the world is finite or infinite. If the Blessed One will elucidate these questions to me, then I will lead the holy life under him. If he will not, then I will abandon the precepts and return to the lay life.

“If the Blessed One knows that the world is eternal, let the Blessed One elucidate to me that the world is eternal; if the Blessed One knows that the world is not eternal, let the Blessed One elucidate that the world is not eternal—in that case, certainly, for one who does not know and lacks the insight, the only upright thing is to say: I do not know, I have not the insight.”

Calmly the Buddha questioned the erring bhikkhu whether his adoption of the holy life was in any way conditional upon the solution of such problems.

“Nay, Lord,” the bhikkhu replied.

The Buddha then admonished him not to waste time and energy over idle speculations detrimental to his moral progress, and said:

“Whoever, Māluṇkyaputta, should say, ‘I will not lead the holy life under the Blessed One until the Blessed One elucidates these questions to me’—that person would die before these questions had ever been elucidated by the Accomplished One.

“It is as if a person were pierced by an arrow thickly smeared with poison, and his friends and relatives were to procure a surgeon, and then he were to say. ‘I will not have this arrow taken out until I know the details of the person by whom I was wounded, nature of the arrow with which I was pierced, etc.’ That person would die before this would ever be known by him.

“In exactly the same way whoever should say, ‘I will not lead the holy life under the Blessed One until he elucidated to me whether the world is eternal or not eternal, whether the world is finite or infinite…’ That person would die before these questions had ever been elucidated by the Accomplished One.

“If it be the belief that the world is eternal, will there be the observance of the holy life? In such a case—No! If it be the belief that the world is not eternal, will there be the observance of the holy life? In that case also—No! But, whether the belief be that the world is eternal or that it is not eternal, there is birth, there is old age, there is death, the extinction of which in this life itself I make known.

“Māluṇkyaputta, I have not revealed whether the world is eternal or not eternal, whether the world is finite or infinite. Why have I not revealed these? Because these are not profitable, do not concern the bases of holiness, are not conducive to disenchantment, to passionlessness, to cessation, to tranquillity, to intuitive wisdom, to enlightenment or to Nibbāna. Therefore I have not revealed these.” 325

According to Buddhism, we are born from the matrix of action (kammayoni). Parents merely provide us with a material layer. Therefore being precedes being. At the moment of conception, it is kamma that conditions the initial consciousness that vitalises the foetus. It is this invisible kammic energy, generated from the past birth, that produces mental phenomena and the phenomena of life in an already extant physical phenomena, to complete the trio that constitutes man.

Dealing with the conception of beings, the Buddha states:

Where three are found in combination, there a germ of life is planted. If mother and father come together, but it is not the mother’s fertile period, and the ‘being-to-be-born’ (gandhabba) is not present, then no germ of life is planted. If mother and father come together, and it is the mother’s fertile period, but the ‘being-to-be-born’ is not present then again no germ of life is planted. If mother and father come together and it is the mother’s fertile period, and the ‘being-to-be-born’ is present, then by the conjunction of these three, a germ of life is there planted. 326

Here gandhabba (= gantabba) does not mean “a class of devas said to preside over the process of conception” 327 but refers to a suitable being ready to be born in that particular womb. This term is used only in this particular connection, and must not be mistaken for a permanent soul.

For a being to be born here, somewhere a being must die. The birth of a being, which strictly means the arising of the aggregates (khandhānaṃ pātubhāvo), or psycho-physical phenomena in this present life, corresponds to the death of a being in a past life; just as, in conventional terms, the rising of the sun in one place means the setting of the sun in another place. This enigmatic statement may be better understood by imagining life as a wave and not as a straight line. Birth and death are only two phases of the same process. Birth precedes death, and death, on the other hand, precedes birth. This constant succession of birth and death connection with each individual life-flux constitutes what is technically known as saṃsāra —recurrent wandering.

What is the ultimate origin of life?

The Buddha positively declares:

Without, cognisable beginning is this saṃsāra. The earliest point of beings who, obstructed by ignorance and fettered by craving, wander and fare on, is not to be perceived. 328

This life-stream flows ad infinitum, as long as it is fed with the muddy waters of ignorance and craving. When these two are completely cut off, then only does the life-stream cease to flow; rebirth ends, as in the case of buddhas and arahants. A first beginning of this life-stream cannot be determined, as a stage cannot be perceived when this life force was not fraught with ignorance and craving.

It should be understood that the Buddha has here referred merely to the beginning of the life stream of living beings. It is left to scientists to speculate on the origin and the evolution of the universe.

XXIII.

The Buddha on the So-Called Creator-God

“I count your Brahmā one th’ unjust among,

Who made a world in which to shelter wrong.”— Jātaka

The Pali equivalent for the creator-god in other religions is either Issara (Skt. Isvara) or Brahmā. In the Tipiṭaka there is absolutely no reference whatever to the existence of a god. On several occasions the Buddha denied the existence of a permanent soul (attā). As to the denial of a creator-god, there are only a few references. Buddha never admitted the existence of a creator whether in the form of a force or a being.

Despite the fact that the Buddha placed no supernatural god over man some scholars assert that the Buddha was characteristically silent on this important controversial question.

The following quotations will clearly indicate the viewpoint of the Buddha towards the concept of a creator-god.

In the Aṇguttara Nikāya the Buddha speaks of three divergent views that prevailed in his time. One of these was: “Whatever happiness or pain or neutral feeling this person experiences all that is due to the creation of a supreme deity (issaranimmāṇahetu).” 329

According to this view we are what we were willed to be by a creator. Our destinies rest entirely in his hands. Our fate is preordained by him. The supposed free will granted to his creation is obviously false.

Criticising this fatalistic view, the Buddha says: “So, then, owing to the creation of a supreme deity men will become murderers, thieves, unchaste, liars, slanderers, abusive, babblers, covetous, malicious and perverse in view. Thus for those who fall back on the creation of a god as the essential reason, there is neither desire nor effort nor necessity to do this deed or abstain from that deed.” 330

In the Devadaha Sutta (DN 11) the Buddha, referring to the self-mortification of naked ascetics, remarks: “If, O bhikkhus, beings experience pain and happiness as the result of a god’s creation, then certainly these naked ascetics must have been created by a wicked god (pāpakena issarena), since they suffer such terrible pain.”

The Kevaḍḍha Sutta narrates a humorous conversation that occurred between an inquisitive bhikkhu and the supposed creator.

A bhikkhu, desiring to know the end of the elements, approached Mahā Brahmā and questioned him thus:

“Where, my friend, do the four great elements—earth, water, fire and air—cease, leaving no trace behind?”

To this the Great Brahmā replied:

“I, brother, am Brahmā, Great Brahmā, the Supreme Being, the Unsurpassed, the Chief, the Victor, the Ruler, the Father of all beings who have been or are to be.”

For the second time the bhikkhu repeated his question, and the Great Brahmā gave the same dogmatic reply.

When the bhikkhu questioned him for the third time, the Great Brahmā took the bhikkhu by the arm, led him aside, and made a frank utterance:

“O Brother, these gods of my suite believe as follows: ‘Brahmā sees all things, knows all things, has penetrated all things.’ Therefore was it that I did not answer you in their presence. I do not know, O brother, where these four great elements—earth, water, fire and air—cease, leaving no trace behind. Therefore it was an evil and a crime, O brother, that you left the Blessed One, and went elsewhere in quest of an answer to this question. Turn back, O brother, and having drawn near to the Blessed One, ask him this question, and as the Blessed One shall explain to you so believe.”

Tracing the origin of Mahā Brahmā, the so-called creator-god, the Buddha comments in the Pātika Sutta (DN 24).

“On this, O disciples, that being who was first born (in a new world evolution) thinks thus: ‘I am Brahmā, the Great Brahmā, the Vanquisher, the All-Seer, the Disposer, the Lord, the Maker, the Creator, the Chief, the Assigner, the Master of Myself, the Father of all that are and are to be. By me are these beings created. And why is that so? A while ago I thought: Would that other beings too might come to this state of being! Such was the aspiration of my mind, and lo! These beings did come.

“And those beings themselves who arose after him, they too think thus: ‘This Worthy must be Brahmā, the Great Brahmā, the Vanquisher, the All-Seer, the Disposer, the Lord, the Maker, the Creator, the Chief, the Assigner, the Master of Myself, the Father of all that are and are to be.

“On this, O disciples, that being who arose first becomes longer-lived, handsomer, and more powerful, but those who appeared after him become shorter lived, less comely, less powerful. And it might well be, O disciples, that some other being, on deceasing from that state, would come to this state (on earth) and so come, he might go forth from the household life into the homeless state. And having thus gone forth, by reason of ardour, effort, devotion, earnestness, perfect intellection, he reaches up to such rapt concentration, that with rapt mind he calls to mind his former dwelling place, but remembers not what went before. He says thus: ‘That Worshipful Brahmā, the Vanquisher, the All-Seer, the Disposer, the Lord, the Maker, the Creator, the Chief, the Assigner, the Master of Myself, the Father of all that are and are to be, he by whom we were created, he is permanent, constant, eternal, un-changing, and he will remain so for ever and ever. But we who were created by that Brahmā, we have come hither all impermanent, transient, unstable, short-lived, destined to pass away.’

“Thus was appointed the beginning of all things, which ye, sirs, declare as your traditional doctrine, to wit, that it has been wrought by an over-lord, by Brahmā.”

In the Bhūridatta Jātaka (No. 543) the Bodhisatta questions the supposed divine justice of the creator as follows:

“He who has eyes can see the sickening sight,

Why does not Brahmā set his creatures right?

If his wide power no limit can restrain,

Why is his hand so rarely spread to bless?

Why are his creatures all condemned to pain?

Why does he not to all give happiness?

Why do fraud, lies, and ignorance prevail?

Why triumphs falsehood—truth and justice fail?

I count you Brahmā one th’unjust among,

Who made a world in which to shelter wrong.”

Refuting the theory that everything is the creation of a Supreme Being, the Bodhisatta states in the Mahābodhi Jātaka (No. 528):

“If there exists some Lord all powerful to fulfil

In every creature bliss or woe, and action good or ill;

That Lord is stained with sin.

Man does but work his will.”

XXIV.

Reasons to Believe in Rebirth

“I recalled my varied lot in former existences.”

— Majjhima Nikāya

How are we to believe in rebirth?

The Buddha is our greatest authority on rebirth. On the very night of his enlightenment, during the first watch, the Buddha developed retrocognitive knowledge which enabled him to read his past lives.

“I recalled,” he declares, “my varied lot in former existences as follows: first one life, then two lives, then three, four, five, ten, twenty, up to fifty lives, then a hundred, a thousand, a hundred thousand and so forth.” 331

During the second watch the Buddha, with clairvoyant vision, perceived beings disappearing from one state of existence and reappearing in another. He beheld the “base and the noble, the beautiful and the ugly, the happy and the miserable, passing according to their deeds.”

These are the very first utterances of the Buddha regarding the question of rebirth. The textual references conclusively prove that the Buddha did not borrow this stern truth of rebirth from any pre-existing source, but spoke from personal knowledge—a knowledge which was supernormal, developed by himself, and which could be developed by others as well. 332

In his first paean of joy (udāna), the Buddha says:

“Through many a birth (anekajāti), wandered I, seeking the builder of this house. Sorrowful indeed is birth again and again (dukkhā jāti punappunaṃ).” 333

In the Dhammacakka Sutta, 334 his very first discourse, the Buddha, commenting on the second Noble truth, states: “This very craving is that which leads to rebirth” (yāyaṃ taṇhā ponobhavikā). The Buddha concludes this discourse with the words: “This is my last birth. Now there is no more rebirth (ayam antimā jāti natthi dāni punabbhavo).”

The Ariyapariyesana Sutta (MN 26) relates that when the Buddha, out of compassion for beings, surveyed the world with his Buddha-vision before he decided to teach the Dhamma, he perceived beings who, with fear, view evil and a world beyond (paralokavajjabhayadassāvino).

In several discourses the Buddha clearly states that beings, having done evil, are, after death (parammaraṇā), born in woeful states, and beings having done good, are born in blissful states. Besides the very interesting Jātaka stories, which deal with his previous lives and which are of ethical importance, the Majjhima Nikāya and the Aṇguttara Nikāya make incidental references to some of the past lives of the Buddha.

In the Ghaīkāra Sutta (MN 81) the Buddha relates to the Venerable Ánanda that he was born as Jotipāla, in the time of the Buddha Kassapa, his immediate predecessor. The Anāthapiṇḍikovāda Sutta (MN 143) describes a nocturnal visit of Anāthapiṇḍika to the Buddha, immediately after his rebirth as a deva. In the Aṇguttara Nikāya, 335 the Buddha alludes to a past birth as Pacetana the wheelwright. In the Saṃyuttta Nikāya, the Buddha cites the names of some Buddhas who preceded him.

An unusual direct reference to departed ones appears in the Parinibbāna Sutta (DN 16). The Venerable Ánanda desired to know from the Buddha the future state of several persons who had died in a particular village. The Buddha patiently described their destinies.

Such instances could easily be multiplied from the Tipiṭaka to show that the Buddha did expound the doctrine of rebirth as a verifiable truth. 336

Following the Buddha’s instructions, his disciples also developed this retrocognitive knowledge and were able to read a limited, though vast, number of their past lives. The Buddha’s power in this direction was limitless.

Certain Indian Rishis, too, prior to the advent of the Buddha, were distinguished for such supernormal powers as clairaudience, clairvoyance, telepathy, telesthesia, and so forth.

Although science takes no cognisance of these supernormal faculties, yet, according to Buddhism, men with highly developed mental concentration cultivate these psychic powers and read their past just as one would recall a past incident of one’s present life. With their aid, independent of the five senses, direct communication of thought and direct perception of other worlds are made possible.

Some extraordinary persons, especially in their childhood, spontaneously develop, according to the laws of association, the memory of their past births and remember fragments of their previous lives. 337 Pythagoras is said to have distinctly remembered a shield in a Grecian temple as having been carried by him in a previous incarnation at the siege of Troy. 338 Somehow or other these wonderful children lose that memory later, as is the case with many infant prodigies.

Experiences of some dependable modern psychics, ghostly phenomena, spirit communication, strange alternate and multiple personalities 339 also shed some light upon this problem of rebirth.

In hypnotic states some can relate experiences of their past lives, while a few others, like Edgar Cayce of America, were able not only to read the past lives of others but also to heal diseases. 340

The phenomenon of secondary personalities has to be explained either as remnants of past personal experiences or as “possession by an invisible spirit.” The former explanation appears more reasonable, but the latter cannot totally be rejected.

How often do we meet persons whom we have never before met, but who, we instinctively feel, are familiar to us? How often do we visit places and instinctively feel impressed that we are perfectly acquainted with those surroundings? 341

The Dhammapada commentary relates the story of a husband and wife who, seeing the Buddha, fell at his feet and saluted him, saying, “Dear son, is it not the duty of sons to care for their mother and father when they have grown old. Why is it that for so long a time you have not shown yourself to us? This is the first time we have seen you?”

The Buddha attributed this sudden outburst of parental love to the fact that they had been his parents several times during his past lives and remarked:

“Through previous association or present advantage

That old love springs up again like the lotus in the water.” 342

There arise in this world highly developed personalities, and Perfect Ones like the Buddhas. Could they evolve suddenly? Could they be the products of a single existence?

How are we to account for personalities like Confucius, Pānini, Buddhaghosa,Homer, and Plato, men of genius like Kālidāsa, Shakespeare, infant prodigies like Ramanujan, Pascal, Mozart, Beethoven, and so forth?

Could they be abnormal if they had not led noble lives and acquired similar experiences in the past? Is it by mere chance that they are born of those particular parents and placed under those favourable circumstances?

Infant prodigies, too, seem to be a problem for scientists. Some medical men are of opinion that prodigies are the outcome of abnormal glands, especially the pituitary, the pineal and the adrenal gland. The extraordinary hypertrophy of glands of particular individuals may also be due to a past kammic cause. But how, by mere hypertrophy of glands, one Christian Heineken could talk within a few hours of his birth, repeat passages from the Bible at the age of one year, answer any question on geography at the age of two, speak French and Latin at the age of three, and be a student of philosophy at the age of four; how John Stuart Mill could read Greek at the age of three; how Macaulay could write a world history at the age of six; how William James Sidis, wonder child of the United States, could read and write at the age of two, speak French, Russian, English, German with some Latin and Greek at the age of eight; how Charles Bennet of Manchester could speak in several languages at the age of three—are wonderful events incomprehensible to non-scientists. 343 Nor does science explain why glands should hypertrophy in just a few and not in all. The real problem remains unsolved.

Heredity alone cannot account for prodigies, “else their ancestry would disclose it, their posterity, in even greater degree than themselves, would demonstrate it.”

The theory of heredity should be supplemented by the doctrine of kamma and rebirth for an adequate explanation of these puzzling problems.

Is it reasonable to believe that the present span of life is the only existence between two eternities of happiness and misery? The few years we spend here, at most but five score years, must certainly be an inadequate preparation for eternity.

If one believes in the present and a future, it is logical to believe in a past.

If there be reason to believe that we have existed in the past, then surely there are no reasons to disbelieve that we shall continue to exist after our present life has apparently ceased. 344

It is indeed a strong argument in favour of past and future lives that “in this world virtuous persons are very often unfortunate and vicious persons prosperous.” 345

We are born into the state created by ourselves. If, in spite of our goodness, we are compelled to lead an unfortunate life, it is due to our past evil kamma. If, in spite of our wickedness, we are prosperous, it is also due to our past good kamma. The present good and bad deeds will, however, produce their due effects at the earliest possible opportunity.

A Western writer says:

“Whether we believe in a past existence or not, it forms the only reasonable hypothesis which bridges certain gaps in human knowledge concerning facts of everyday life. Our reason tells us that this idea of past birth and kamma alone can explain, for example, the degrees of differences that exist between twins; how men like Shakespeare with a very limited experience are able to portray, with marvellous exactitude, the most diverse types of human character, scenes, and so forth, of which they could have no actual knowledge, why the work of the genius invariably transcends his experience, the existence of infant precocity, and the vast diversity in mind and morals, in brain and physique, in conditions, circumstances and environments, observable throughout the world.”

What Do Kamma and Rebirth Explain?

They account for the problem of suffering for which we ourselves are responsible.

They explain the inequality of mankind.

They account for the arising of geniuses and infant prodigies.

They explain why identical twins, who are physically alike, enjoying equal privileges, exhibit totally different characteristics, mentally, morally, temperamentally and intellectually.

They account for the dissimilarities amongst children of the same family, though heredity may account for the similarities.

They account for the extraordinary innate abilities of some men.

They account for the moral and intellectual differences between parents and children.

They explain how infants spontaneously develop such passions as greed, anger and jealousy.

They account for instinctive likes and dislikes at first sight.

They explain how in us are found “a rubbish heap of evil and a treasure-house of good.”

They account for the unexpected outburst of passion in a highly civilised person, and for the sudden transformation of a criminal into a saint.

They explain how profligates are born to saintly parents, and saintly children to profligates.

They explain how, in one sense, we are the result of what we were, we will be the result of what we are; and, in another sense, we are not absolutely what we were, and we will not be absolutely what we are.

They explain the causes of untimely deaths and unexpected changes in fortune.

Above all they account for the arising of omniscient, perfect spiritual teachers, like the Buddhas, who possess incomparable physical, mental, and intellectual characteristics.

XXV.

The Wheel of Life (Paṭicca Samuppāda)

“No God, no Brahmā can be found,

No matter of this wheel of life,

Just bare phenomena roll

Dependent on conditions all!”

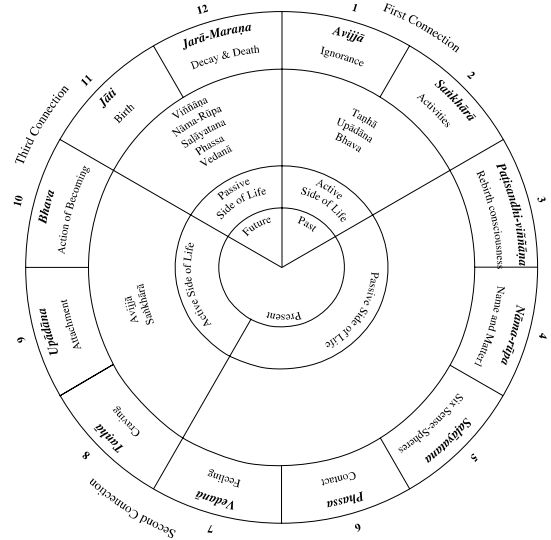

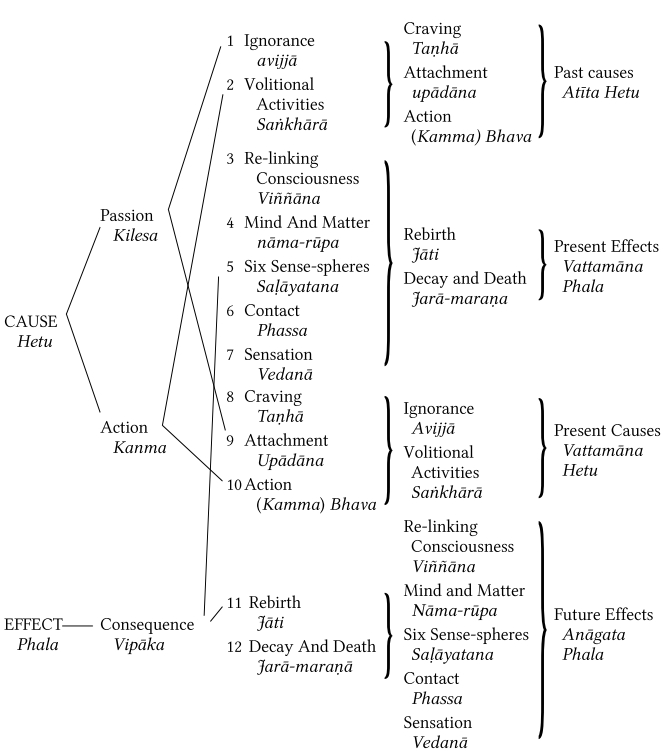

The process of rebirth has been fully explained by the Buddha in the paṭicca samuppāda.

Paṭicca means “because of” or “dependent upon”; samuppāda means”arising” or “origination.” Although the literal meaning of the term is “arising because of” or ” dependent arising or origination,” it is applied to the whole causal formula which consists of twelve interdependent causes and effects, technically called paccayaandpaccayuppanna.

The method of thepaticca samuppādashould be understood as follows:

Because of A arises B. Because of B arises C.

When there is no A, there is no B.

When there is no B, there is no C.

In other words—”this being so, that is; this not being so, that is not.” (imasmiṃ sati, idam hoti; imasmiṃ asati, idaṃ na hoti.)

Paṭicca samuppāda is a discourse on the process of birth and death, and not a philosophical theory of the evolution of the world. It deals with the cause of rebirth and suffering with a view to helping men to get rid of the ills of life. It makes no attempt to solve the riddle of an absolute origin of life.

It merely explains the “simple happening of a state, dependent on its antecedent state.” 346

Ignorance (avijjā) of the truth of suffering, its cause, its end, and the way to its end, is the chief cause that sets the wheel of life in motion. In other words, it is the not-knowingness of things as they truly are or of oneself as one really is. It clouds all right understanding.

“Ignorance is the deep delusion wherein we here so long are circling round,” 347 says the Buddha.

When ignorance is destroyed and turned into knowingness, all causality is shattered as in the case of the Buddhas and arahants.

In Itivuttaka 1:14 the Buddha states, “Those who have destroyed delusion and broken through the dense darkness, will wander no more: causality exists no more for them.”

Ignorance of the past, future, both past and future and dependent origination is also regarded as avijjā.

Dependent on Ignorance Arise Conditioning Activities (saṇkhārā)

Saṇkhārā is a multi-significant term which should be understood according to the context. Here the term signifies immoral (akusala), moral (kusala) and unshakable (āneñja) volitions (cetanā) which constitute kamma that produces rebirth. The first embraces all volitions in the twelve types of immoral consciousness; the second, all volitions in the eight types of beautiful (sobhana) moral consciousness and the five types of moral rūpa-jhāna consciousness; the third, all volitions in the four types of morala rūpa-jhāna consciousness.

Saṇkhārā, as one of the five aggregates, implies fifty of the fifty-two mental states, excluding feeling and perception.

There is no proper English equivalent which gives the exact connotation of this Pali term.

The volitions of the four supramundane path consciousness (lokuttara maggacitta) are not regarded as saṇkhārā because they tend to eradicate ignorance. Wisdom (paññā) is predominant in supramundane types of consciousness while volition (cetanā) is predominant in the mundane types of consciousness.

All moral and immoral thoughts, words and deeds are included in saṇkhārā. Actions, whether good or bad, which are directly rooted in, or indirectly tainted with ignorance, and which must necessarily produce their due effects, tend to prolong wandering in saṃsāra. Nevertheless, good deeds, freed from greed, hate and delusion, are necessary to get rid of the ills of life. Accordingly the Buddha compares his Dhamma to a raft whereby one crosses the ocean of life. The activities of Buddhas and arahants, however, are not treated as saṇkhārā as they have eradicated ignorance.

Ignorance is predominant in immoral activities, while it is latent in moral activities. Hence both moral and immoral activities are regarded as caused by ignorance.

Dependent on Conditioning Activities Arise Consciousness (viññāṇa)

Dependent on past conditioning activities arises relinking or rebirth-consciousness (paṭisandhi-viññāṇa) in a subsequent birth. It is so called because it links the past with the present, and is the initial consciousness one experiences at the moment of conception.

Viññāṇa strictly denotes the nineteen types of rebirth-consciousness (paṭisandhi-viññāṇa) described in the Abhidhamma. All the thirty-two types of resultant consciousness (vipāka-citta) experienced during lifetime are also implied by the term.

The foetus in the mother’s womb is formed by the combination of this relinking-consciousness with the sperm and ovum cells of the parents. In this consciousness are latent all the past impressions, characteristics and tendencies of that particular individual life-flux.

This rebirth-consciousness is regarded as pure 348 as it is either devoid of immoral roots of lust, hatred, and delusion 349 or accompanied by moral roots. 350

Dependent on Consciousness Arise Mind and Matter (nāmarūpa)

Simultaneous with the arising of the relinking-consciousness there occur mind and matter (nāma-rūpa) or, as some scholars prefer to say, “corporeal organism.”

The second and third factors (saṇkhārā and viññāṇa) pertain to the past and present lives of an individual. The third and fourth factors (viññāṇa and nāma-rūpa) on the contrary, are contemporaneous.

This compound nāma-rūpa should be understood as nāma (mind) alone, rūpa (matter) alone, and nāma-rūpa (mind and matter) together. In the case of formless planes (arūpa) there arises only mind; in the case of mindless (asañña) planes, only matter; in the case of sense realm (kāma) and realms of form (rūpa), both mind and matter.

Nāma here means the three aggregates—feeling (vedanā), perception (saññā) and mental states (saṇkhārā)—that arise simultaneous with the relinking-consciousness. Rūpa means the three decads— kāya (body), bhāva (sex), and vatthu (seat of consciousness)—that also arise simultaneous with the relinking-consciousness, conditioned by past kamma.

The body-decad is composed of the four elements: 1) the element of extension (paṭhavī), 2) the element of cohesion (āpo), 3) the element of heat (tejo), and 4) the element of motion (vāyo). Its derivatives (upādā rūpa) are: 5) colour (vaṇṇa), 6) odour (gandha), 7) taste (rasa), 8) nutritive essence (ojā), 9) vitality (jīvitindriya), and 10) body (kāya).

Sex-decad and base decad also consist of the first nine and sex (bhāva) and seat of consciousness (vatthu) respectively.

From this it is evident that sex is determined by past kamma at the very conception of the being.

Here kāya means the sensitive part of the body (pasāda).

Sex is not developed at the moment of conception but the potentiality is latent. Neither the heart nor the brain, the supposed seat of consciousness, has been evolved at the moment of conception, but the potentiality of the seat is latent.

In this connection it should be remarked that the Buddha did not definitely assign a specific seat for consciousness as he has done with the other senses. It was the cardiac theory (the view that the heart is the seat of consciousness) that prevailed in his time, and this was evidently supported by the Upanishads.

The Buddha could have accepted the popular theory, but he did not commit himself. In the Pahāna (the Book of Relations) the Buddha refers to the seat of consciousness, in such indirect terms as “yamrūpamnissāya—depending on that material thing,” without positively asserting whether that rūpa was either the heart (hadaya) or the brain. But, according to the view of commentators like Venerable Buddhaghosa and Anuruddha, the seat of consciousness is definitely the heart. It should be understood that the Buddha neither accepted nor rejected the popular cardiac theory.

Dependent on Mind and Matter, the Six Sense-bases (saḷāyatana) Arise

During the embryonic period the six sense-bases (saḷāyatana) gradually evolve from these psycho-physical phenomena in which are latent infinite potentialities. The insignificant infinitesimally small speck now develops into a complex six-senses machine.

The human machine is very simple in its beginning but very complex in its end. Ordinary machines, on the other hand, are complex in the beginning but very simple in the end. The force of a finger is sufficient to operate even a most gigantic machine.

The six-senses-human machine now operates almost mechanically without any agent like a soul to act as the operator. All the six senses—eye, ear, nose, tongue, body and mind—have their respective objects and functions. The six sense-objects such as forms, sounds, odours, sapids, tangibles and mental objects collide with their respective sense-organs giving rise to six types of consciousness.

Dependent on the Six Sense-bases, Contact (phassa) Arises

The conjunction of the sense-bases, sense-objects, and the resultant consciousness is contact (phassa) which is purely subjective and impersonal.

The Buddha states:

Because of eye and forms, visual consciousness arises; contact is the conjunction of the three. Because of ear and sounds, arises auditory consciousness; because of nose and odours, arises olfactory consciousness; because of tongue and sapids, arises gustatory consciousness; because of body and tangibles, arises tactile consciousness; because of mind and mental objects, arises mind-consciousness. The conjunction of these three is contact. 351

It should not be understood that mere collision is contact (na saṇgatimatto eva phasso).

Dependent on Contact, Feelings (vedanā) Arise.

Strictly speaking, it is feeling that experiences an object when it comes in contact with the senses. It is this feeling that experiences the desirable or undesirable fruits of an action done in this or in a previous birth. Besides this mental state there is no soul or any other agent to experience the result of the action.

Feeling or, as some prefer to say, sensation, is a mental state common to all types of consciousness. Chiefly there are three kinds of feeling: pleasurable (somanassa), unpleasurable (domanassa), and neutral (adukkhamasukha). With physical pain (dukkha) and physical happiness (sukha) there are altogether five kinds of feelings. The neutral feeling is also termed upekkhā which may be indifference or equanimity.

According to Abhidhamma there is only one type of consciousness accompanied by pain. Similarly there is only one accompanied by happiness. Two are connected with an unpleasurable feeling. Of the eighty-nine types of consciousness, in the remaining eighty-five are found either a pleasurable or a neutral feeling

It should be understood here that nibbānic bliss is not associated with any kind of feeling. Nibbānic bliss is certainly the highest happiness (ānaṃparamaṃ sukhaṃ), but it is the happiness of relief from suffering. It is not the enjoyment of any pleasurable object.

Dependent on Feeling, Arises Craving (taṇhā)

Craving, beside ignorance, is the most important factor in the “dependent origination.” Attachment, thirst, clinging are some renderings for this Pali term.

Craving is threefold—namely, craving for sensual pleasures (kāmataṇhā), craving for sensual pleasures associated with the view of eternalism, (bhavataṇhā) i.e., enjoying pleasures thinking that they are imperishable, and craving for sensual pleasures with the view of nihilism (vibhavataṇhā) i.e., enjoying pleasures thinking that everything perishes after death. The last is the materialistic standpoint.

Bhavataṇhā and vibhavataṇhā are also interpreted asattachment to realms of form (rūpabhava) and formless realms (arūpabhava) respectively. Usually these two terms are rendered by craving for existence and non-existence.

There are six kinds of craving corresponding to the six sense objects such as form, sound and so on. They become twelve when they are treated as internal and external. They are reckoned as thirty-six when viewed as past, present and future. When multiplied by the foregoing three kinds of craving, they amount to one hundred and eight.

It is natural for a worldling to develop a craving for the pleasures of sense. To overcome sense-desires is extremely difficult.

The most powerful factors in the wheel of life are ignorance and craving, the two main causes of the dependent origination. Ignorance is shown as the past cause that conditions the present; and craving, the present cause that conditions the future.

Dependent on Craving is Grasping (upādāna)

Grasping is intense craving. Taṇhā is like groping in the dark to steal an object. Upādāna corresponds to the actual stealing of the object. Grasping is caused by both attachment and error. It gives rise to the false notions of “I” and “mine.”

Grasping is fourfold—namely, sensuality, false views, adherence to rites and ceremonies, and the theory of a soul.

The last two are also regarded as false views.

Dependent on Grasping Arises Becoming (bhava)

Bhava literally means becoming. It is explained as both moral and immoral actions which constitute kamma (kammabhava)—active process of becoming and the different planes of existence (upapattibhava)—passive process of becoming.

The subtle difference between saṇkhārā and kammabhava is that the former pertains to the past and the latter to the present life. By both are meant kammic activities. It is only the kammabhava that conditions the future birth.

Dependent on Becoming Arises Birth (jāti)

This refers to birth in a subsequent life. Birth, strictly speaking, is the arising of the psycho-physical phenomena (khandhānaṃ pātubhāvo).

Dependent on Birth Arises Old Age, Sickness and Death (jarāmaraṇa)

Old age and death are the inevitable results of birth.

The Reverse Order of the Paṭicca Samuppāda

If, on account of a cause, an effect arises, then, if the cause ceases, the effect also must cease.

The reverse order of the paṭicca samuppāda will make the matter clear.

Old age and death are only possible in and with a psycho-physical organism, that is to say, a six-senses-machine. Such an organism must be born, therefore it presupposes birth. But birth is the inevitable result of past kamma or action, which is conditioned by grasping due to craving. Such craving appears when feeling arises. Feeling is the outcome of contact between senses and objects.

Therefore it presupposes organs of sense which cannot exist without mind and body. Mind originates with a rebirth-consciousness, conditioned by activities, due to ignorance of things as they truly are.

The whole formula may be summed up thus:

Dependent on ignorance arise conditioning activities;

Dependent on conditioning activities arises relinking-consciousness;

Dependent on relinking-consciousness arise mind and matter;

Dependent on mind and matter arise the six spheres of sense;

Dependent on the six spheres of sense arises contact;

Dependent on contact arises feeling;

Dependent on feeling arises craving;

Dependent on craving arises grasping;

Dependent on grasping arises becoming (kamma bhava);

Dependent on actions arises birth;

Dependent on birth arise decay, death, sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, and despair;

Thus does the entire aggregate of suffering arise.

The complete cessation of ignorance leads to the cessation of conditioning activities;

The cessation of conditioning activities leads to the cessation of relinking-consciousness;

The cessation of relinking-consciousness leads to the cessation of mind and matter;

The cessation of mind and matter leads to the cessation of the six spheres of sense;

The cessation of the six spheres of sense leads to the cessation of contact;

The cessation of contact leads to the cessation of feeling;

The cessation of feeling leads to the cessation of craving;

The cessation of craving leads to the cessation of grasping;

The cessation of grasping leads to the cessation of becoming;

The cessation of actions leads to the cessation of birth;

The cessation of birth leads to the cessation of decay, death, sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, and despair.

Thus does the cessation of this entire aggregate of suffering result.

The first two of these twelve factors pertain to the past, the middle eight to the present, and the last two to the future.

Of them, moral and immoral activities (saṇkhārā) and actions (bhava) are regarded as kamma.

Ignorance (avijjā), craving (taṇhā), and grasping (upādāna) are regarded as passions or defilements (kilesa).

Relinking-consciousness (paṭisandhi-viññāṇa), mind and matter (nāma-rūpa), spheres of sense (saḷāyatana), contact (phassa), feeling (vedanā), birth (jāti), decay and death (jarāmaraṇa) are regarded as effects (vipāka).

Thus ignorance, activities, craving, grasping and kamma, the five causes of the past, condition the present five effects (phala)—namely, relinking-consciousness, mind and matter, spheres of sense, contact, and feeling.

In the same way craving, grasping, kamma, ignorance, and activities of the present condition the above five effects of the future.

This process of cause and effect continues ad infinitum. A beginning of this process cannot be determined as it is impossible to conceive of a time when this life-flux was not encompassed by ignorance. But when this ignorance is replaced by wisdom and the life-flux realises the āna dhatu, then only does the rebirth process terminate.

“‘Tis Ignorance entails the dreary round

—now here, now there—of countless births and deaths.”

“But, no hereafter waits for him who knows!” 352

——

——

Diagram 5. Paṭicca Samuppāda — “Dependent Origination”

XXVI.

Modes of Birth and Death

“Again, again the slow wits seek rebirth,

Again, again comes birth and dying comes,

Again, again men bear it to the grave.”— Saṃyutta Nikāya

Paṭicca-samuppāda describes the process of rebirth in subtle technical terms and assigns death to one of the following four causes:

1. Exhaustion of the reproductive kammic energy (kammakkhaya).

The Buddhist belief is that, as a rule, the thought, volition, or desire, which is extremely strong during lifetime, becomes predominant at the time of death and conditions the subsequent birth. In this last thought-process is present a special potentiality. When the potential energy of this reproductive (janaka) kamma is exhausted, the organic activities of the material form in which is embodied the life-force, cease even before the end of the life span in that particular place.

This often happens in the case of beings who are born in states of misery (apāya) but it can happen in other planes too.

2. The expiration of the life-term (āyukkhaya), which varies in different planes.

Natural deaths, due to old age, may be classed under this category.

There are different planes of existence with varying age-limits. Irrespective of the kammic force that has yet to run, one must, however, succumb to death when the maximum age-limit is reached.

If the reproductive kammic force is extremely powerful, the kammic energy rematerialises itself in the same plane or, as in the case of devas, in some higher realm.

3. The simultaneous exhaustion of the reproductive kammic energy and the expiration of the life-term (ubhayakkhaya).

4. The opposing action of a stronger kamma unexpectedly obstructing the flow of the reproductive kamma before the life-term expires (upacchedaka-kamma).

Sudden untimely deaths of persons and the deaths of children are due to this cause.

A more powerful opposing force can check the path of a flying arrow and bring it down to the ground. So a very powerful kammic force of the past is capable of nullifying the potential energy of the last thought-process, and may thus destroy the psychic life of the being.

The death of Venerable Devadatta, for instance, was due to a destructive kamma which he committed during his lifetime.

The first three are collectively called “timely deaths” (kāla-maraṇa), and the fourth is known as “untimely death” (akāla-maraṇa).

An oil lamp, for instance, may get extinguished owing to any of the following four causes—namely, the exhaustion of the wick, the exhaustion of oil, simultaneous exhaustion of both wick and oil, or some extraneous cause like a gust of wind.

So may death be due to any of the foregoing four causes.

Explaining thus the causes of death, Buddhism states that there are four modes of birth, 1) egg-born beings (aṇḍdaja), 2) womb-born beings (jalābuja), 3) moisture-born beings (saṃsedaja), and 4) beings having spontaneous births (opapātika).

This broad classification embraces all living beings.

Birds and oviparous snakes belong to the first division.

The womb-born creatures comprise all human beings, some devas inhabiting the earth, and some animals that take conception in a mother’s womb.

Embryos, using moisture as nidus for their growth, like certain lowly forms of animal life, belong to the third class.

Beings having a spontaneous birth are generally invisible to the physical eye. Conditioned by their past kamma, they appear spontaneously, without passing through an embryonic stage. Petas and devas normally, and Brahmās belong to this class.

XVII.

Planes of Existence

“Not to be reached by going is world’s end.”

— Aṇguttara Nikāya

According to Buddhism the earth, an almost insignificant speck in the universe, is not the only habitable world, and humans are not the only living beings. Indefinite are world systems and so are living beings. Nor is “the impregnated ovum the only route to rebirth.” By traversing one cannot reach the end of the world, 353 says the Buddha.

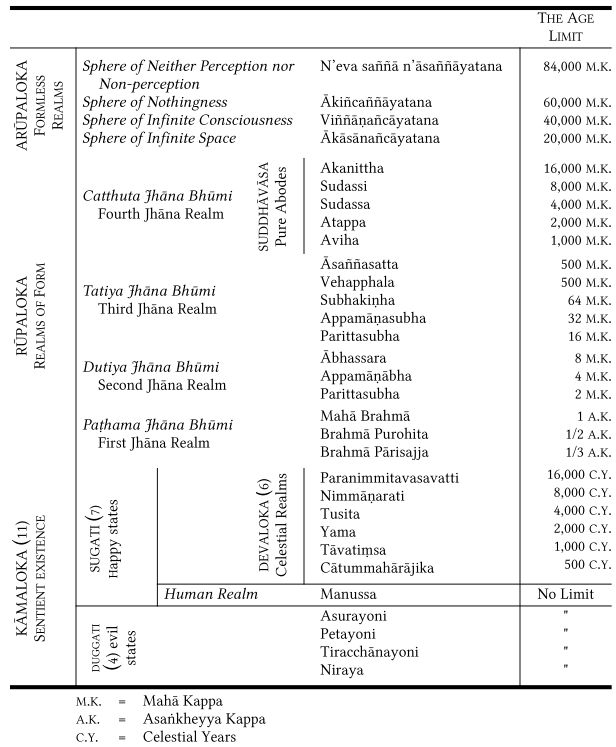

Births may take place in different spheres of existence. There are altogether thirty-one places in which beings manifest themselves according to their moral or immoral kamma.

There are four states of unhappiness (apāya) 354 which are viewed both as mental states and as places:

1. Niraya (ni + aya = “devoid of happiness”), woeful states where beings atone for their evil kamma. They are not eternal hells where beings are subject to endless suffering. Upon the exhaustion of the evil kamma there is a possibility for beings born in such states to be reborn in blissful states as the result of their past good actions.

2. Tiracchāna-yoni (tiro = across; acchāna = going), the animal kingdom. Buddhist belief is that beings are born as animals on account of evil kamma. There is, however, the possibility for animals to be born as human beings as a result of the good kamma accumulated in the past. Strictly speaking, it should be more correct to state that kamma which manifested itself in the form of a human being, may manifest itself in the form of an animal or vice versa, just as an electric current can be manifested in the forms of light, heat, and motion successively—one not necessarily being evolved from the other.

It may be remarked that at times certain animals, particularly dogs and cats, live a more comfortable life than even some human beings due to their past good kamma.

It is one’s kamma that determines the nature of one’s material form which varies according to the skilfulness or unskilfulness of one’s actions.

3. Peta-yoni lit., departed beings, or those absolutely devoid of happiness. They are not disembodied spirits of ghosts. They possess deformed physical forms of varying magnitude, generally invisible to the naked eye. They have no planes of their own, but live in forests, dirty surroundings, etc. The Peta Vatthu (Book VIII of the Kuddaka Nikāya) deals exclusively with the stories of these unfortunate beings. The Saṃyutta Nikāya also relates some interesting accounts of these petas.

Describing the pathetic state of a peta, the Venerable Moggallāna says:

Just now as I was descending Vultures’ Peak Hill, I saw a skeleton going through the air, and vultures, crows, and falcons kept flying after it, pecking at its ribs, pulling it apart while it uttered cries of pain. To me, friend, came this thought: O but this is wonderful! O but this is marvellous that a person will come to have such a shape, that the individuality acquired will come to have such a shape.

“This being,” the Buddha remarked, “was a cattle-butcher in his previous birth, and as the result of his past kamma he was born in such a state.” 355

According to the Questions of Milinda there are four kinds of petas—namely, the vantāsikas who feed on vomit, the khuppipāsino who hunger and thirst, the nijjhāmataṇhika, who are consumed by thirst, and the paradattūpajīvino who live on the gifts of others.

As stated in the Tirokuḍḍa Sutta 356 these last mentioned petas share the merit performed by their living relatives in their names, and could thereby pass on to better states of happiness.

4. Asura-yoni—the place of the asura demons. Asura, literally, means those who do not shine or those who do not sport. They are also another class of unhappy beings similar to the petas. They should be distinguished from the asuras who are opposed to the devas.

Next to these four unhappy states (duggati) are the seven happy states (sugati):

1. Manussa—the realm of human beings. 357

The human realm is a mixture of both pain and happiness. Bodhisattas prefer the human realm as it is the best field to serve the world and perfect the requisites of buddhahood. Buddhas are always born as human beings.

2. Cātummahārājika—the lowest of the heavenly realms where the guardian deities of the four quarters of the firmament reside with their followers.

3. Tāvatiṃsa—lit., “thirty-three”—the celestial realm of the thirty-three devas 358 where deva Sakka is the king. The origin of the name is attributed to a story which states that thirty-three selfless volunteers led by Magha (another name for Sakka), having performed charitable deeds, were born in this heavenly realm. It was in this heaven that the Buddha taught the Abhidhamma to the devas for three months.

4. Yāma—”the realm of the yāma devas.” That which destroys pain is yāma.

5. Tusita—lit., “happy dwellers” is “the realm of delight.”

The bodhisattas who have perfected the requisites of buddhahood reside in this plane until the opportune moment comes for them to appear in the human realm to attain buddhahood. The bodhisatta Metteyya, the future Buddha, is at present residing in this realm awaiting the right opportunity to be born as a human being and become a Buddha. The Bodhisatta’s mother, after death, was born in this realm as a deva. From here she repaired to Tāvatimsa Heaven to listen to the Abhidhamma taught by the Buddha.

6. Nimmānaratī— “the realm of the devas who delight in the created mansions.”

7. Paranimmitavasavattī—”the realm of the devas who make others’ creation serve their own ends.”

The last six are the realms of the devas whose physical forms are more subtle and refined than those of human beings and are imperceptible to the naked eye. These celestial beings too are subject to death as all mortals are. In some respects, such as their constitution, habitat, and food they excel humans, but do not as a rule transcend them in wisdom. They have spontaneous births, appearing like youths and maidens of fifteen or sixteen years of age.

These six celestial planes are temporary blissful abodes where beings are supposed to live enjoying fleeting pleasures of sense.

The four unhappy states (duggati) and the seven happy states (sugati) are collectively termed kāmaloka —saense sphere.

Superior to these sensuous planes are the Brahmā realms or rūpaloka (realms of form) where beings delight in jhānic bliss, achieved by renouncing sense-desires.

Rūpaloka consists of sixteen realms according to the jhānas or ecstasies cultivated. They are listed below, and are depicted in Diagram 6.

Brahmā Pārisajja—The Realm of the Brahmā’s Retinue.

Brahmā Purohita—The Realm of the Brahmā’s Ministers.

Mahā Brahmā—The Realm of the Great Brahmās.

The highest of the first three is Mahā Brahmā. It is so called because the dwellers in this Realm excel others in happiness, beauty, and age-limit owing to the intrinsic merit of their mental development.

The Plane of the Second Jhāna:

Parittābhā—The Realm of Minor Lustre.

Appamānābhā—The Realm of Infinite Lustre.

Ábhassarā—The Realm of the Radiant Brahmās.

The Plane of the Third Jhāna:

Parittasubhā— The Realm of the Brahmās of Minor Aura.

Appamānasubhā—The Realm of the Brahmās of Infinite Aura.

Subhakinhā—The Realm of the Brahmās of Steady Aura.

The Plane of the Fourth Jhāna:

Vehapphala—The Realm of the Brahmās of Great Reward.

Asaññasatta—The Realm of Mindless Beings.

Suddhāvāsa—The Pure Abodes which are further subdivided into five, viz:

Údassi—The Clear-Sighted Realm,

Only those who have cultivated the jhānas are born in these higher planes. Those who have developed the first jhāna are born in the first plane; those who have developed the second and third jhānas are born in the second plane; those who have developed the fourth and fifth jhānas are born in the third and fourth planes respectively.

The first grade of each plane is assigned to those who have developed the jhānas to an ordinary degree, the second to those who have developed the jhānas to a greater extent, and the third to those who have gained a complete mastery over the jhānas.

In the eleventh plane, called the asaññasatta, beings are born without a consciousness. Here only a material flux exists. Mind is temporarily suspended while the force of the jhāna lasts. Normally both mind and matter are inseparable. By the power of meditation it is possible, at times, to separate matter from mind as in this particular case. When an arahant attains the nirodha samāpatti, too, his consciousness ceases to exist temporarily. Such a state is almost inconceivable to us. But there may be inconceivable things which are actual facts.

The Suddhāvāsas or Pure Abodes are the exclusive planes of anāgāmis or never-returners. Ordinary beings are not born in these states. Those who attain anāgāmi in other planes are reborn in these pure abodes. Later, they attain arahantship and live in those planes until their life-term ends.

There are four other planes called arūpaloka which are totally devoid of matter or bodies. Buddhists maintain that there are realms where mind alone exists without matter. “Just as it is possible for an iron bar to be suspended in the air because it has been flung there, and it remains as long as it retains any unexpended momentum, even so the formless being appears through being flung into that state by powerful mind-force, there it remains till that momentum is expended. This is a temporary separation of mind and matter, which normally co-exist.” 359

It should be mentioned that there is no sex distinction in the rūpaloka and the arūpaloka.

The arūpaloka is divided into four planes according to the four arūpa jhānas:

Ákāsānañcāyatana—the sphere of the conception of infinite space.

Viññāṇañcāyatana —the sphere of the conception of infinite consciousness.

Ákiñcaññāyatana —the sphere of the conception of nothingness.