The Buddha and his Teachings

Namo tassa Bhagavato arahanto Sammā Sambuddhassa!

Homage to the Exalted, the Worthy,

the Fully Enlightened One!

I.

The Buddha From Birth to Renunciation

A unique being, an extraordinary man arises in this world for the benefit of the many, for the happiness of the many, out of compassion for the world, for the good, benefit, and happiness of gods and men. Who is this unique being? It is the Tathāgata, the exalted, fully Enlightened One.

—Aṇguttara Nikāya — AN 1:13/A I 22.

Birth

On the full moon day of May, 1 in the year 623 BCE 2 there was born in the Lumbini Park 3 at Kapilavatthu, 4 on the Indian borders of present Nepal, a noble prince who was destined to be the greatest religious teacher of the world.

His father 5 was King Suddhodana of the aristocratic Sākya 6 clan and his mother was Queen Mahā Māyā. As the beloved mother died seven days after his birth, Mahā Pajāpatī Gotamī, her younger sister, who was also married to the king, adopted the child, entrusting her own son, Nanda, to the care of the nurses.

Great were the rejoicings of the people over the birth of this illustrious prince. An ascetic of high spiritual attainments, named Asita, also known as Kāladevala, was particularly pleased to hear this happy news, and being a tutor of the king, visited the palace to see the royal babe. The king, who felt honoured by his unexpected visit, carried the child up to him in order to make the child pay him due reverence, but, to the surprise of all, the child’s legs turned and rested on the matted locks of the ascetic. Instantly, the ascetic rose from his seat and, foreseeing with his supernormal vision the child’s future greatness, saluted him with clasped hands. 7 The royal father did likewise.

The great ascetic smiled at first and then was sad. Questioned regarding his mingled feelings, he answered that he smiled because the prince would eventually become a Buddha, an enlightened one, and he was sad because he would not be able to benefit by the superior wisdom of the Enlightened One owing to his prior death and rebirth in a formless plane (arūpaloka). 8

Naming Ceremony

On the fifth day after the prince’s birth, he was named Siddhattha, which means “wish fulfilled.” His family name was Gotama. 9

In accordance with the ancient Indian custom, many learned brahmins were invited to the palace for the naming ceremony. Amongst them there were eight distinguished men. Examining the characteristic marks of the child, seven of them raised two fingers each, indicative of two alternative possibilities, and said that he would either become a Universal Monarch or a Buddha. But the youngest, Kondañña, 10 who excelled others in wisdom, noticing the hair on the forehead turned to the right, raised only one finger and convincingly declared that the prince would definitely retire from the world and become a buddha.

Ploughing Festival

A very remarkable incident took place in his childhood. It was an unprecedented spiritual experience which, later, during his search after truth, served as a key to his enlightenment. 11

To promote agriculture, the king arranged for a ploughing festival. It was indeed a festive occasion for all, as both nobles and commoners decked in their best attire, participated in the ceremony. On the appointed day, the king, accompanied by his courtiers, went to the field, taking with him the young prince together with the nurses. Placing the child on a screened and canopied couch under the cool shade of a solitary rose-apple tree to be watched by the nurses, the king participated in the ploughing festival. When the festival was at its height of gaiety the nurses too stole away from the prince’s presence to catch a glimpse of the wonderful spectacle.

In striking contrast to the mirth and merriment of the festival it was all calm and quiet under the rose-apple tree. All the conditions conducive to quiet meditation being there, the pensive child, young in years but old in wisdom, sat cross-legged and seized the opportunity to commence that all-important practice of intense concentration on the breath—on exhalations and inhalations—which gained for him then and there that one-pointedness of mind known as samādhi and he thus developed the first jhāna (ecstasy). 12 The child’s nurses, who had abandoned their precious charge to enjoy themselves at the festival, suddenly realising their duty, hastened to the child and were amazed to see him sitting cross-legged, plunged in deep meditation. The king hearing of it, hurried to the spot and, seeing the child in meditative posture, saluted him, saying, “This, dear child, is my second obeisance.”

Education

As a royal child, Prince Siddhattha must have received an education that became a prince although no details are given about it. As a scion of the warrior race he received special training in the art of warfare.

Married Life

At the early age of sixteen, he married his beautiful cousin Princess Yasodharā 13 who was of equal age. For nearly thirteen years, after his happy marriage, he led a luxurious life, blissfully ignorant of the vicissitudes of life outside the palace gates. Of his luxurious life as prince, he states:

I was delicate, excessively delicate. In my father’s dwelling three lotus-ponds were made purposely for me. Blue lotuses bloomed in one, red in another, and white in another. I used no sandal-wood that was not of Kāsi. 14 My turban, tunic, dress and cloak, were all from Kāsi.

Night and day a white parasol was held over me so that I might not be touched by heat or cold, dust, leaves or dew.

There were three palaces built for me—one for the cold season, one for the hot season, and one for the rainy season. During the four rainy months, I lived in the palace for the rainy season without ever coming down from it, entertained all the while by female musicians. Just as, in the houses of others, food from the husks of rice together with sour gruel is given to the slaves and workmen, even so, in my father’s dwelling, food with rice and meat was given to the slaves and workmen. 15

With the march of time, truth gradually dawned upon him. His contemplative nature and boundless compassion did not permit him to spend his time in the mere enjoyment of the fleeting pleasures of the royal palace. He knew no personal grief but he felt a deep pity for suffering humanity. Amidst comfort and prosperity, he realised the universality of sorrow.

Renunciation

Prince Siddhattha reflected thus:

Why do I, being subject to birth, decay, disease, death, sorrow and impurities, thus search after things of like-nature. How, if I, who am subject to things of such nature, realise their disadvantages and seek after the unattained, unsurpassed, perfect security which is Nibbāna!” 16

“Cramped and confined is household life, a den of dust, but the life of the homeless one is as the open air of heaven! Hard is it for him who bides at home to live out as it should be lived the holy life in all its perfection, in all its purity. 17

One glorious day as he went out of the palace to the pleasure park to see the world outside, he came in direct contact with the stark realities of life. Within the narrow confines of the palace he saw only the rosy side of life, but the dark side, the common lot of mankind, was purposely veiled from him. What was mentally conceived, he, for the first time, vividly saw in reality. On his way to the park his observant eyes met the strange sights of a decrepit old man, a diseased person, a corpse and a dignified hermit. 18 The first three sights convincingly proved to him, the inexorable nature of life, and the universal ailment of humanity. The fourth signified the means to overcome the ills of life and to attain calm and peace. These four unexpected sights served to increase the urge in him to loathe and renounce the world.

Realising the worthlessness of sensual pleasures, so highly prized by the worldling, and appreciating the value of renunciation in which the wise seek delight, he decided to leave the world in search of truth and eternal peace.

When this final decision was taken after much deliberation, the news of the birth of a son was conveyed to him while he was about to leave the park. Contrary to expectations, he was not overjoyed but regarded his first and only offspring as an impediment. An ordinary father would have welcomed the joyful tidings, but Prince Siddhattha, the extraordinary father as he was, exclaimed —”An impediment (rāhu) has been born; a fetter has arisen.” The infant son was accordingly named Rāhula 19 by his grandfather.

The palace was no longer a congenial place to the contemplative Prince Siddhattha. Neither his charming young wife nor his lovable infant son could deter him from altering the decision he had taken to renounce the world. He was destined to play an infinitely more important and beneficial role than a dutiful husband and father or even as a king of kings. The allurements of the palace were no more cherished objects of delight to him. Time was ripe to depart.

He ordered his favourite charioteer Channa to saddle the horse Kaṇhaka and went to the suite of apartments occupied by the princess. Opening the door of the chamber, he stood on the threshold and cast his dispassionate glance on the wife and child who were fast asleep.

Great was his compassion for the two dear ones at this parting moment. Greater was his compassion for suffering humanity. He was not worried about the future worldly happiness and comfort of the mother and child as they had everything in abundance and were well protected. It was not that he loved them the less, but he loved humanity more.

Leaving all behind, he stole away with a light heart from the palace at midnight, and rode into the dark, attended only by his loyal charioteer. Alone and penniless he set out in search of truth and peace. Thus, did he renounce the world. It was not the renunciation of an old man who has had his fill of worldly life. It was not the renunciation of a poor man who had nothing to leave behind. It was the renunciation of a prince in the full bloom of youth and in the plenitude of wealth and prosperity—a renunciation unparalleled in history. It was in his twenty-ninth year that Prince Siddhattha made this historic journey.

He journeyed far and, crossing the river Anomā, rested on its banks. Here he shaved his hair and beard and handing over his garments and ornaments to Channa with instructions to return to the palace, assumed the simple yellow garb of an ascetic and led a life of voluntary poverty.

The ascetic Siddhattha, who once lived in the lap of luxury, now became a penniless wanderer, living on what little the charitably-minded gave of their own accord.

He had no permanent abode. A shady tree or a lonely cave sheltered him by day or night. Bare-footed and bare-headed, he walked in the scorching sun and in the piercing cold. With no possessions to call his own, but a bowl to collect his food and robes just sufficient to cover the body, he concentrated all his energies on the quest of truth.

Search

Thus as a wanderer, a seeker after what is good, searching for the unsurpassed peace, he approached Álāra Kālāma, a distinguished ascetic, and said: “I desire, friend Kālāma to lead the holy life in this dispensation of yours.”

Thereupon Álāra Kālāma told him: “You may stay with me, O Venerable One. Of such sort is this teaching that an intelligent man before long may realise by his own intuitive wisdom his master’s doctrine, and abide in the attainment thereof.”

Before long, he learnt his doctrine, but it brought him no realisation of the highest truth.

Then there came to him the thought: “When Álāra Kālāma declared:

‘Having myself realised by intuitive knowledge the doctrine, I abide in the attainment thereof,’ it could not have been a mere profession of faith; surely Álāra Kālāma lives having understood and perceived this doctrine.”

So he went to him and said “How far, friend Kālāma, does this doctrine extend which you yourself have with intuitive wisdom realised and attained?”

Upon this Álāra Kālāma made known to him the Realm of Nothingness (ākiñcaññāyatana), 20 an advanced stage of concentration.

Then it occurred to him: “Not only in Álāra Kālāma are to be found faith, energy, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom. I too possess these virtues. How now if I strive to realise that doctrine whereof Álāra Kālāma says that he himself has realised and abides in the attainment thereof!”

So, before long, he realised by his own intuitive wisdom that doctrine and attained to that state, but it brought him no realisation of the highest truth.

Then he approached Álāra Kālāma and said: “Is this the full extent, friend Kālāma, of this doctrine of which you say that you yourself have realised by your wisdom and abide in the attainment thereof?”

“But I also, friend, have realised thus far in this doctrine, and abide in the attainment thereof.”

The unenvious teacher was delighted to hear of the success of his distinguished pupil. He honoured him by placing him on a perfect level with himself and admiringly said:

Happy, friend, are we, extremely happy, in that we look upon such a venerable fellow-ascetic like you! That same doctrine which I myself have realised by my wisdom and proclaim, having attained thereunto, have you yourself realised by your wisdom and abide in the attainment thereof; and that doctrine you yourself have realised by your wisdom and abide in the attainment thereof, that have I myself realised by my wisdom and proclaim, having attained thereunto. Thus the doctrine which I know, and also do you know; and, the doctrine which you know, that I know also. As I am, so are you; as you are, so am I. Come, friend, let both of us lead the company of ascetics.

The ascetic Gotama was not satisfied with a discipline and a doctrine which only led to a high degree of mental concentration, but did not lead to “disgust, detachment, cessation (of suffering), tranquillity, intuition, enlightenment, and Nibbāna.” Nor was he anxious to lead a company of ascetics even with the co-operation of another generous teacher of equal spiritual attainment, without first perfecting himself. It was, he felt, a case of the blind leading the blind. Dissatisfied with his teaching, he politely took his leave from him.

In those happy days when there were no political disturbances the intellectuals of India were preoccupied with the study and exposition of some religious system or other. All facilities were provided for those more spiritually inclined to lead holy lives in solitude in accordance with their temperaments and most of these teachers had large followings of disciples. So it was not difficult for the Ascetic Gotama to find another religious teacher who was more competent than the former.

On this occasion, he approached one Uddaka Rāmaputta and expressed his desire to lead the holy life in his dispensation. He was readily admitted as a pupil.

Before long the intelligent ascetic Gotama mastered his doctrine and attained the final stage of mental concentration, the realm of neither-perception-nor-non-perception (nevasaññānāsaññāyatana), 21 revealed by his teacher. This was the highest stage in worldly concentration when consciousness becomes so subtle and refined that it cannot be said that a consciousness either exists or not. Ancient Indian sages could not proceed further in spiritual development.

The noble teacher was delighted to hear of the success of his illustrious royal pupil. Unlike his former teacher, the present one honoured him by inviting him to take full charge of all the disciples as their teacher. He said: “Happy friend, are we; yea, extremely happy, in that we see such a venerable fellow-ascetic as you! The doctrine which Rāma knew, you know; the doctrine which you know, Rāma knew. As was Rāma so are you; as you are, so was Rāma. Come, friend, henceforth you shall lead this company of ascetics.”

Still he felt that his quest of the highest truth was not achieved. He had gained complete mastery of his mind, but his ultimate goal was far ahead. He was seeking for the Highest, the Nibbāna, the complete cessation of suffering, the total eradication of all forms of craving. “Dissatisfied with this doctrine too, he departed thence, content therewith no longer.”

He realised that his spiritual aspirations were far higher than those under whom he chose to learn. He realised that there was none capable enough to teach him what he yearned for—the highest truth. He also realised that the highest truth is to be found within oneself and ceased to seek external aid.

——

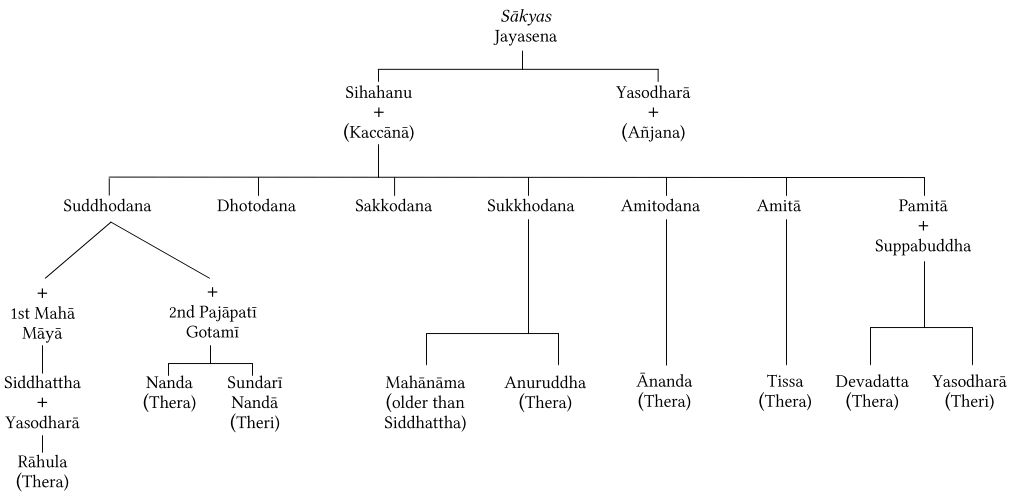

Diagram 1. Prince Siddhattha’s Genealogical Table (Father’s Side)

——

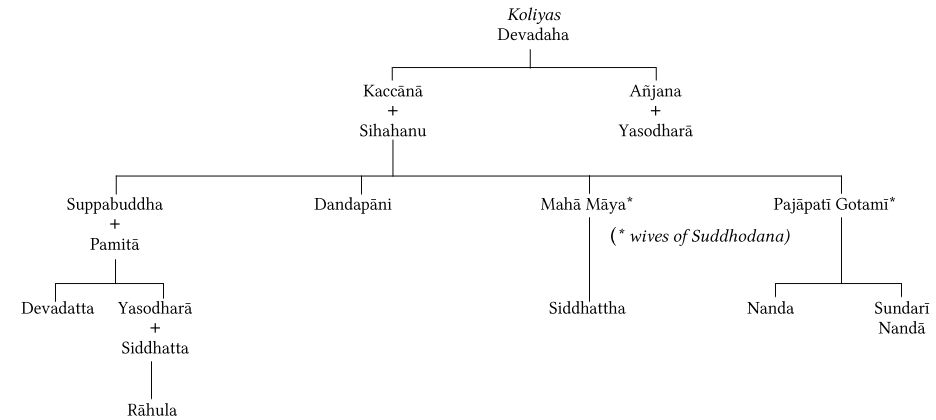

Diagram 2. Prince Siddhattha’s Genealogical Table (Mother’s Side)

II.

His Struggle for Enlightenment

Easy to do are things that are bad

and not beneficial to self,

But very, very hard to do indeed

is that which is beneficial and good.—Dhp 163

Struggle

Meeting with disappointment, but not discouraged, the Ascetic Gotama seeking for the incomparable peace, the highest truth, wandered through the district of Magadha and arrived in due course at Uruvelā, the market town of Senāni. There he spied a lovely spot of ground, a charming forest grove, a flowing river with pleasant sandy fords, and hard by was a village where he could obtain his food. Then he thought thus:

Lovely, indeed, O Venerable One, is this spot of ground, charming is the forest grove, pleasant is the flowing river with sandy fords, and hard by is the village where I could obtain food. Suitable indeed is this place for spiritual exertion for those noble scions who desire to strive. (Ariyapariyesana Sutta, MN 26)

The place was congenial for his meditation. The atmosphere was peaceful. The surroundings were pleasant. The scenery was charming. Alone, he resolved to settle down there to achieve his desired object.

Hearing of his renunciation, Kondañña, the youngest brahmin who predicted his future, and four sons of the other sages—Bhaddiya, Vappa, Mahānāma, and Assaji—also renounced the world and joined his company.

In the ancient days in India, great importance was attached to rites, ceremonies, penances and sacrifices. It was then a popular belief that no deliverance could be gained unless one leads a life of strict asceticism. Accordingly, for six long years the Ascetic Gotama made a superhuman struggle practising all forms of severest austerity. His delicate body was reduced to almost a skeleton. The more he tormented his body the farther his goal receded from him.

How strenuously he struggled, the various methods he employed, and how he eventually succeeded are graphically described in his own words in various suttas.

Mahā Saccaka Sutta (MN 36) describes his preliminary efforts thus:

Then the following thought occurred to me:

“How if I were to clench my teeth, press my tongue against the palate, and with (moral) thoughts hold down, subdue and destroy my (immoral) thoughts!’

So I clenched my teeth, pressed my tongue against the palate and strove to hold down, subdue, destroy my (immoral) thoughts with (moral) thoughts. As I struggled thus, perspiration streamed forth from my armpits.

Like unto a strong man who might seize a weaker man by head or shoulders and hold him down, force him down, and bring into subjection, even so did I struggle.

Strenuous and indomitable was my energy. My mindfulness was established and unperturbed. My body was, however, fatigued and was not calmed as a result of that painful endeavour—being overpowered by exertion. Even though such painful sensations arose in me, they did not at all affect my mind.

Then I thought thus: ‘How if I were to cultivate the non-breathing ecstasy!’

Accordingly, I checked inhalation and exhalation from my mouth and nostrils. As I checked inhalation and exhalation from mouth and nostrils, the air issuing from my ears created an exceedingly great noise. Just as a blacksmith’s bellows being blown make an exceedingly great noise, even so was the noise created by the air issuing from my ears when I stopped breathing.

Nevertheless, my energy was strenuous and indomitable. Established and unperturbed was my mindfulness. Yet my body was fatigued and was not calmed as a result of that painful endeavour—being over-powered by exertion.

Even though such painful sensations arose in me, they did not at all affect my mind.

Then I thought to myself: ‘How if I were to cultivate that non-breathing exercise!’

Accordingly, I checked inhalation and exhalation from mouth, nostrils, and ears. And as I stopped breathing from mouth, nostrils and ears, the (imprisoned) airs beat upon my skull with great violence. Just as if a strong man were to bore one’s skull with a sharp drill, even so did the airs beat my skull with great violence as I stopped breathing. Even though such painful sensations arose in me, they did not at all affect my mind.

Then I thought to myself: ‘How if I were to cultivate that non-breathing ecstasy again!’

Accordingly, I checked inhalation and exhalation from mouth, nostrils, and ears. And as I stopped breathing thus, terrible pains arose in my head. As would be the pains if a strong man were to bind one’s head tightly with a hard leather thong, even so were the terrible pains that arose in my head. Nevertheless, my energy was strenuous. Such painful sensations did not affect my mind.

Then I thought to myself: ‘How if I were to cultivate that non-breathing ecstasy again!’

Accordingly, I stopped breathing from mouth, nostrils, and ears. As I checked breathing thus, plentiful airs pierced my belly. Just as if a skilful butcher or a butcher’s apprentice were to rip up the belly with a sharp butcher’s knife, even so plentiful airs pierced my belly.

Nevertheless, my energy was strenuous. Such painful sensations did not affect my mind.

Again I thought to myself: ‘How if I were to cultivate that non-breathing ecstasy again!’

Accordingly, I checked inhalation and exhalation from mouth, nostrils, and ears. As I suppressed my breathing thus, a tremendous burning pervaded my body. Just as if two strong men were each to seize a weaker man by his arms and scorch and thoroughly burn him in a pit of glowing charcoal, even so did a severe burning pervade my body.

Nevertheless, my energy was strenuous. Such painful sensations did not affect my mind.

Thereupon the deities who saw me thus said: ‘The ascetic Gotama is dead.’ Some remarked: ‘The ascetic Gotama is not dead yet, but is dying.” While some others said: “The ascetic Gotama is neither dead nor is dying but an arahant is the ascetic Gotama. Such is the way in which an arahant abides.”

Change of Method: Abstinence from Food

“Then I thought to myself: ‘How if I were to practise complete abstinence from food!’

Then deities approached me and said: ‘Do not, good sir, practise total abstinence from food. If you do practise it, we will pour celestial essence through your body’s pores; with that you will be sustained.’

And I thought: ‘If I claim to be practising starvation, and if these deities pour celestial essence through my body’s pores and I am sustained thereby, it would be a fraud on my part.’ So I refused them, saying ‘There is no need.’

Then the following thought occurred to me: ‘How if I take food little by little, a small quantity of the juice of green gram, or vetch, or lentils, or peas!’

As I took such small quantity of solid and liquid food, my body became extremely emaciated. Just as are the joints of knot-grasses or bulrushes, even so were the major and minor parts of my body, owing to lack of food. Just as is the camel’s hoof, even so were my hips for want of food. Just as is a string of beads, even so did my backbone stand out and bend in, for lack of food. Just as the rafters of a dilapidated hall fall this way and that, even so appeared my ribs through lack of sustenance. Just as in a deep well may be seen stars sunk deep in the water, even so did my eye-balls appear deep sunk in their sockets, being devoid of food. Just as a bitter pumpkin, when cut while raw, will by wind and sun get shrivelled and withered, even so did the skin of my head get shrivelled and withered, due to lack of sustenance.

And I, intending to touch my belly’s skin, would instead seize my backbone. When I intended to touch my backbone, I would seize my belly’s skin. So was I that, owing to lack of sufficient food, my belly’s skin clung to the backbone, and I, on going to pass excreta or urine, would in that very spot stumble and fall down, for want of food. And I stroked my limbs in order to revive my body. Lo, as I did so, the rotten roots of my body’s hairs fell from my body owing to lack of sustenance. The people who saw me said: ‘The ascetic Gotama is black.’ Some said, ‘The ascetic Gotama is not black but blue.’ Some others said: ‘The ascetic Gotama is neither black nor blue but tawny.’ To such an extent was the pure colour of my skin impaired owing to lack of food.

Then the following thought occurred to me: ‘Whatsoever ascetics or brahmins of the past have experienced acute, painful, sharp and piercing sensations, they must have experienced them to such a high degree as this and not beyond. Whatsoever ascetics and brahmins of the future will experience acute, painful, sharp and piercing sensations, they too will experience them to such a high degree and not beyond. Yet by all these bitter and difficult austerities I shall not attain to excellence, worthy of supreme knowledge and insight, transcending those of human states. Might there be another path for enlightenment!'”

Temptation of Māra the Evil One

His prolonged painful austerities proved utterly futile. They only resulted in the exhaustion of his valuable energy. Though physically a superman his delicately nurtured body could not possibly stand the great strain. His graceful form completely faded almost beyond recognition. His golden coloured skin turned pale, his blood dried up, his sinews and muscles shrivelled up, his eyes were sunk and blurred. To all appearance he was a living skeleton. He was almost on the verge of death.

At this critical stage, while he was still intent on the highest (padhāna), abiding on the banks of the Nerañjarā river, striving and contemplating in order to attain to that state of perfect security, came Namuci, 22 uttering kind words thus: 23

“You are lean and deformed. Near to you is death.

A thousand parts (of you belong) to death; to life (there remains) but one. Live, O good sir! Life is better. Living, you could perform merit.

By leading a life of celibacy and making fire sacrifices, much merit could be acquired. What will you do with this striving? Hard is the path of striving, difficult and not easily accomplished.”

Māra reciting these words stood in the presence of the Exalted One.

To Māra who spoke thus, the Exalted One replied:

“O Evil One, kinsman of the heedless! You have come here for your own sake.

Even an iota of merit is of no avail. To them who are in need of merit it behoves you, Māra, to speak thus.

Confidence (saddhā), self-control (tapa), perseverance (viriya), and wisdom (paññā) are mine. Me who am thus intent, why do you question about life?

Even the streams of rivers will this wind dry up. Why should not the blood of me who am thus striving dry up?

When blood dries up, the bile and phlegm also dry up. When my flesh wastes away, more and more does my mind get clarified. Still more do my mindfulness, wisdom, and concentration become firm.

While I live thus, experiencing the utmost pain, my mind does not long for lust! Behold the purity of a being!

Sense-desires (kāmā) are your first army. The second is called aversion for the holy life (arati). The third is hunger and thirst 24 (khuppipāsā). The fourth is called craving (taṇhā). The fifth is sloth and torpor (thīna-middha). The sixth is called fear (bhīru). The seventh is doubt 25 (vicikicchā), and the eighth is detraction and obstinacy (makkha-thambha). The ninth is gain (lobha), praise (siloka) and honour (sakkāra), and that ill-gotten fame (yasa). The tenth is the extolling of oneself and contempt for others (attukkaṃsana-paravambhana).

This, Namuci, is your army, the opposing host of the Evil One. That army the coward does not overcome, but he who overcomes obtains happiness.

This Muñja 26 do I display! What boots life in this world! Better for me is death in the battle than that one should live on, vanquished! 27

Some ascetics and brahmins are not seen plunged in this battle. They know not nor do they tread the path of the virtuous.

Seeing the army on all sides with Māra arrayed on elephant, I go forward to battle. Māra shall not drive me from my position. That army of yours, which the world together with gods conquers not, by my wisdom I go to destroy as I would an unbaked bowl with a stone.

Controlling my thoughts, and with mindfulness well-established, I shall wander from country to country, training many a disciple.

Diligent, intent, and practising my teaching, they, disregarding you, will go where having gone they grieve not.”

The Middle Path

The ascetic Gotama was now fully convinced from personal experience of the utter futility of self-mortification which, though considered indispensable for deliverance by the ascetic philosophers of the day, actually weakened one’s intellect, and resulted in lassitude of spirit. He abandoned for ever this painful extreme as did he the other extreme of self-indulgence which tends to retard moral progress. He conceived the idea of adopting the Golden Mean which later became one of the salient features of his teaching.

He recalled how when his father was engaged in ploughing, he sat in the cool shade of the rose-apple tree, absorbed in the contemplation of his own breath, which resulted in the attainment of the first jhāna (ecstasy). 28 Thereupon he thought: “Well, this is the path to enlightenment.”

He realised that enlightenment could not be gained with such an utterly exhausted body: Physical fitness was essential for spiritual progress. So he decided to nourish the body sparingly and took some coarse food both hard and soft.

The five favourite disciples who were attending on him with great hopes thinking that whatever truth the Ascetic Gotama would comprehend, that would he impart to them, felt disappointed at this unexpected change of method and leaving him and the place too, went to Isipatana, saying that “the Ascetic Gotama had become luxurious, had ceased from striving, and had returned to a life of comfort.”

At a crucial time when help was most welcome his companions deserted him leaving him alone. He was not discouraged, but their voluntary separation was advantageous to him though their presence during his great struggle was helpful to him. Alone, in sylvan solitudes, great men often realise deep truths and solve intricate problems.

Dawn of Truth

Regaining his lost strength with some coarse food, he easily developed the first jhāna which he gained in his youth. By degrees he developed the second, third and fourth jhānas as well.

By developing the jhānas he gained perfect one-pointedness of the mind. His mind was now like a polished mirror where everything is reflected in its true perspective.

Thus with thoughts tranquillised, purified, cleansed, free from lust and impurity, pliable, alert, steady, and unshakable, he directed his mind to the knowledge as regards “the reminiscence of past births” (pubbenivāsānussati-ñāṇa).

He recalled his varied lots in former existences as follows: first one life, then two lives, then three, four, five, ten, twenty, up to fifty lives; then a hundred, a thousand, a hundred thousand; then the dissolution of many world cycles, then the evolution of many world cycles, then both the dissolution and evolution of many world cycles. In that place he was of such a name, such a family, such a caste, such a dietary, such the pleasure and pain he experienced, such his life’s end. Departing from there, he came into existence elsewhere. Then such was his name, such his family, such his caste, such his dietary, such the pleasure and pain he did experience, such life’s end. Thence departing, he came into existence here.

Thus he recalled the mode and details of his varied lots in his former births.

This, indeed, was the first knowledge that he realised in the first watch of the night.

Dispelling thus the ignorance with regard to the past, he directed his purified mind to “the perception of the disappearing and reappearing of beings” (cutūpapāta-ñāṇa). With clairvoyant vision, purified and supernormal, he perceived beings disappearing from one state of existence and reappearing in another; he beheld the base and the noble, the beautiful and the ugly, the happy and the miserable, all passing according to their deeds. He knew that these good individuals, by evil deeds, words, and thoughts, by reviling the Noble Ones, by being misbelievers, and by conforming themselves to the actions of the misbelievers, after the dissolution of their bodies and after death, had been born in sorrowful states. He knew that these good individuals, by good deeds, words, and thoughts, by not reviling the Noble Ones, by being right believers, and by conforming themselves to the actions of the right believers, after the dissolution of their bodies and after death, had been born in happy celestial worlds.

Thus with clairvoyant supernormal vision he beheld the disappearing and the reappearing of beings.

This, indeed, was the second knowledge that he realised in the middle watch of the night.

Dispelling thus the ignorance with regard to the future, he directed his purified mind to “the comprehension of the cessation of corruptions” 29 (āsavakkhaya ñāṇa).

He realised in accordance with fact: “this is sorrow,” “this, the arising of sorrow,” “this, the cessation of sorrow,” “this, the path leading to the cessation of sorrow.” Likewise in accordance with the fact he realised, “These are the corruptions,” “this, the arising of corruptions,” “this, the cessation of corruptions,” “this, the path leading to the cessation of corruptions.” Thus cognising, thus perceiving, his mind was delivered from the corruption of sensual craving; from the corruption of craving for existence; from the corruption of ignorance.

Being delivered, he knew, “Delivered am I,” 30 and he realised, “rebirth is ended; fulfilled the holy life; done what was to be done; there is no more of this state again.” 31

This was the third knowledge that he realised in the last watch of the night.

Ignorance was dispelled, and wisdom arose; darkness vanished, and light arose.

III.

Buddhahood

The Tathāgatas are only teachers.

After a stupendous struggle of six strenuous years, in his 35th year the Ascetic Gotama, unaided and unguided by any supernatural agency, and solely relying on his own efforts and wisdom, eradicated all defilements, ended the process of grasping, and, realising things as they truly are by his own intuitive knowledge, became a Buddha—an enlightened or awakened one.

Thereafter he was known as Buddha Gotama, 32 one of a long series of Buddhas that appeared in the past and will appear in the future.

He was not born a Buddha, but became a Buddha by his own efforts.

Characteristics of the Buddha

The Pali term Buddha is derived from “budh,” to understand, or to be awakened. As he fully comprehended the four noble truths and as he arose from the slumbers of ignorance he is called a Buddha. Since he not only comprehends but also expounds the doctrine and enlightens others, he is called a Sammā Sambuddha—a fully enlightened One—to distinguish him from paccekabuddhas 33 who only comprehend the doctrine but are incapable of enlightening others.

Before his enlightenment he was called bodhisatta 34 which means one who is aspiring to attain buddhahood.

Every aspirant to Buddhahood passes through the bodhisatta period—a period of intensive exercise and development of the qualities of generosity, discipline, renunciation, wisdom, energy, endurance, truthfulness, determination, benevolence and perfect equanimity.

In a particular era there arises only one Sammā Sambuddha. Just as certain plants and trees can bear only one flower even so one world-system (lokadhātu) can bear only one Sammā Sambuddha.

The Buddha was a unique being. Such a being arises but rarely in this world, and is born out of compassion for the world, for the good, benefit, and happiness of gods and men. The Buddha is called acchariya manussa as he was a wonderful man. He is called amatassa dātā as he is the giver of deathlessness. He is called varado as he is the giver of the purest love, the profoundest wisdom, and the highest truth. He is also called dhammassāmi as he is the Lord of the Dhamma (doctrine).

As the Buddha himself says, “he is the accomplished one (tathāgata), the worthy one (arahaṃ), the fully enlightened one (sammā sambuddha), the creator of the un-arisen way, the producer of the un-produced way, the proclaimer of the un-proclaimed way, the knower of the way, the beholder of the way, the cogniser of the way.” 35

The Buddha had no teacher for his enlightenment. “Na me ācariyo atthi” 36 — A teacher have I not—are his own words. He did receive his mundane knowledge from his lay teachers, 37 but teachers he had none for his supramundane knowledge which he himself realised by his own intuitive wisdom.

If he had received his knowledge from another teacher or from another religious system such as Hinduism in which he was nurtured, he could not have said of himself as being the incomparable teacher (ahaṃ satthā anuttaro). 38 In his first discourse, he declared that light arose in things not heard before.

During the early period of his renunciation, he sought the advice of the distinguished religious teachers of the day, but he could not find what he sought in their teachings. Circumstances compelled him to think for himself and seek the truth. He sought the truth within himself. He plunged into the deepest profundities of thought, and he realised the ultimate truth which he had not heard or known before. Illumination came from within and shed light on things which he had never seen before.

As he knew everything that ought to be known and as he obtained the key to all knowledge, he is called sabbaññū (omniscient one). This supernormal knowledge he acquired by his own efforts continued through a countless series of births.

Who is the Buddha?

Once a certain brahmin named Dona, noticing the characteristic marks of the footprint of the Buddha approached him and questioned him.

“Your Reverence will be a deva?” 39

“No, indeed, brahmin, a deva am I not,” replied the Buddha.

“Then Your Reverence will be a gandhabba?” 40

“No, indeed, brahmin, a Gandhabba am I not.”

“A Yakkha then?” 41

“No, indeed, brahmin, not a Yakkha.”

“Then Your Reverence will be a human being?”

“No, indeed, brahmin, a human being am I not.”

“Who, then, pray, will Your Reverence be?”

The Buddha replied that he had destroyed defilements which condition rebirth as a deva, gandhabba, yakkha, or a human being and added:

As a lotus, fair and lovely,

By the water is not soiled,

By the world am I not soiled;

Therefore, brahmin, am I Buddha. 42

The Buddha does not claim to be an incarnation (avatāra) of the Hindu god Vishnu, who, as the Bhagavad Gītā 43 charmingly sings, is born again and again in different periods to protect the righteous, to destroy the wicked, and to establish the Dharma (right).

According to the Buddha countless are the gods (devas) who are also a class of beings subject to birth and death; but there is no one supreme god, who controls the destinies of human beings and who possesses a divine power to appear on earth at different intervals, employing a human form as a vehicle. 44

Nor does the Buddha call himself a “saviour” who freely saves others by his personal salvation. The Buddha exhorts his followers to depend on themselves for their deliverance, since both defilement and purity depend on oneself. One cannot directly purify or defile another. 45 Clarifying his relationship with his followers and emphasizing the importance of self-reliance and individual striving, the Buddha plainly states:

“You yourselves should make an exertion.

The tathāgatas are only teachers.” 46

The Buddha only indicates the path and method whereby he delivered himself from suffering and death and achieved his ultimate goal. It is left for his faithful adherents who wish their release from the ills of life to follow the path.

“To depend on others for salvation is negative, but to depend on oneself is positive.” Dependence on others means a surrender of one’s effort.

“Be you isles unto yourselves; be you a refuge unto yourselves; seek no refuge in others.” 47

These significant words uttered by the Buddha in his last days are very striking and inspiring. They reveal how vital is self-exertion to accomplish one’s ends, and how superficial and futile it is to seek redemption through benign saviours, and crave for illusory happiness in an afterlife through the propitiation of imaginary gods by fruitless prayers and meaningless sacrifices.

The Buddha was a human being. As a man he was born, as a Buddha, he lived, and as a Buddha, his life came to an end. Though human, he became an extraordinary man owing to his unique characteristics. The Buddha laid stress on this important point and left no room for anyone to fall into the error of thinking that he was an immortal being. It has been said of him that there was no religious teacher who was “ever so godless as the Buddha, yet none was so god-like.” 48 In his own time, the Buddha was no doubt highly venerated by his followers, but he never arrogated to himself any divinity.

The Buddha’s Greatness

Born a man, living as a mortal, by his own exertion he attained that supreme state of perfection called Buddhahood, and without keeping his enlightenment to himself, he proclaimed to the world the latent possibilities and the invincible power of the human mind. Instead of placing an unseen Almighty God over man, and giving the man a subservient position in relation to such a conception of divine power, he demonstrated how the man could attain the highest knowledge and supreme enlightenment by his own efforts. He thus raised the worth of man. He taught that man can gain his deliverance from the ills of life and realise the eternal bliss of tathāgata without depending on an external God or mediating priests. He taught the egocentric, power-seeking world the noble ideal of selfless service. He protested against the evils of the caste-system that hampered the progress of mankind and advocated equal opportunities for all. He declared that the gates of deliverance were open to all, in every condition of life, high or low, saint or sinner, who would care to turn a new leaf and aspire to perfection. He raised the status of downtrodden women, and not only brought them to a realisation of their importance to society but also founded the first religious order for women. For the first time in the history of the world, he attempted to abolish slavery. He banned the sacrifice of unfortunate animals and brought them within his compass of loving-kindness. He did not force his followers to be slaves either to his teachings or to himself, but granted complete freedom of thought and admonished his followers to accept his words not merely out of regard for him but after subjecting them to a thorough examination “even as the wise would test gold by burning, cutting, and rubbing it on a piece of touchstone.” He comforted the bereaved mothers like Paācārā and Kisāgotamī by his consoling words. He ministered to the deserted sick like Putigatta Tissa Thera with his own hands. He helped the poor and the neglected like Rajjumālā and Sopāka and saved them from an untimely and tragic death. He ennobled the lives of criminals like Aṇgulimāla and courtesans like Ambapāli. He encouraged the feeble, united the divided, enlightened the ignorant, clarified the mystic, guided the deluded, elevated the base, and dignified the noble. The rich and the poor, the saint and the criminal, loved him alike. His noble example was a source of inspiration to all. He was the most compassionate and tolerant of teachers.

His will, wisdom, compassion, service, renunciation, perfect purity, exemplary personal life, the blameless methods that were employed to propagate the Dhamma and his final success—all these factors have compelled about one fifth of the population of the world to hail the Buddha as the greatest religious teacher that ever lived on earth.

Paying a glowing tribute to the Buddha, Sri Radhakrishnan writes:

In Gautama the Buddha we have a master mind from the East second to none so far as the influence on the thought and life of the human race is concerned, and sacred to all as the founder of a religious tradition whose hold is hardly less wide and deep than any other. He belongs to the history of the world’s thought, to the general inheritance of all cultivated men, for, judged by intellectual integrity, moral earnestness, and spiritual insight, he is undoubtedly one of the greatest figures in history. 49

In the Three Greatest Men in History H. G. Wells states:

In the Buddha you see clearly a man, simple, devout, lonely, battling for light, a vivid human personality, not a myth. He too gave a message to mankind universal in character. Many of our best modern ideas are in closest harmony with it. All the miseries and discontents of life are due, he taught, to selfishness. Before a man can become serene he must cease to live for his senses or himself. Then he merges into a greater being. Buddhism in different language called men to self-forgetfulness 500 years before Christ. In some ways he was nearer to us and our needs. He was more lucid upon our individual importance in service than Christ and less ambiguous upon the question of personal immortality.

The Poet Tagore calls him the greatest man ever born.

In admiration of the Buddha, Fausböll, a Danish scholar says, “The more I know him, the more I love him.”

A humble follower of the Buddha would modestly say: “The more I know him, the more I love him; the more I love him, the more I know him.”

IV.

After the Enlightenment

“Happy in this world is non-attachment.”

In the memorable forenoon, immediately preceding the morn of his enlightenment, as the Bodhisatta was seated under the Ajapāla banyan tree in close proximity to the bodhi tree, 50 a generous lady, named Sujātā, unexpectedly offered him some rich milk rice, specially prepared by her with great care.

This substantial meal he ate, and after his enlightenment, the Buddha fasted for seven weeks, and spent a quiet time, in deep contemplation, under the bodhi tree and in its neighbourhood.

The Seven Weeks

First Week

Throughout the first week, the Buddha sat under the bodhi tree in one posture, experiencing the bliss of emancipation (vimutti-sukha, i.e., the fruit of arahantship).

After those seven days had elapsed, the Buddha emerged from the state of concentration, and in the first watch of the night, thoroughly reflected on “the dependent arising” (paṭicca samuppāda) in direct order thus: “When this (cause) exists, this (effect) is; with the arising of this (cause), this effect arises.” 51

Dependent on ignorance (avijjā) arise moral and immoral conditioning activities (saṇkhārā).

Dependent on conditioning activities arises (relinking) consciousness (viññāṇa).

Dependent on (relinking) consciousness arise mind and matter (nāma-rūpa).

Dependent on mind and matter arise the six spheres of sense (saḷāyatana).

Dependent on the six spheres of sense arises contact (phassa).

Dependent on contact arises feeling (vedanā).

Dependent on feeling arises craving (taṇhā).

Dependent on craving arises grasping (upādāna).

Dependent on grasping arises becoming (bhava).

Dependent on becoming arises birth (jāti).

Dependent on birth arise decay (jarā), death (maraṇa), sorrow (soka), lamentation (parideva), pain (dukkha), grief (domanassa), and despair (upāyāsa).

Thus does this whole mass of suffering originate.

Thereupon the Exalted One, knowing the meaning of this, uttered, at that time, this paean of joy:

“When, indeed, the truths become manifest unto the strenuous, meditative brāhmaṇa, 52 then do all his doubts vanish away, since he knows the truth together with its cause.”

In the middle watch of the night the Exalted One thoroughly reflected on “the dependent arising” in reverse order thus: “When this cause does not exist, this effect is not; with the cessation of this cause, this effect ceases.

With the cessation of ignorance, conditioning activities cease.

With the cessation of conditioning activities (relinking) consciousness ceases.

With the cessation of (relinking) consciousness, mind and matter cease.

With the cessation of mind and matter, the six spheres of sense cease.

With the cessation of the six spheres of sense, contact ceases.

With the cessation of contact, feeling ceases.

With the cessation of feeling, craving ceases.

With the cessation of craving, grasping ceases.

With the cessation of grasping, becoming ceases.

With the cessation of becoming, birth ceases.

With the cessation of birth, decay, death, sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, and despair cease.

Thus does this whole mass of suffering cease.

Thereupon the Exalted One, knowing the meaning of this, uttered, at that time, this paean of joy (udāna):

“When, indeed, the truths become manifest unto the strenuous and meditative brāhmaṇa, then all his doubts vanish away since he has understood the destruction of the causes.”

In the third watch of the night, the Exalted One reflected on “dependent arising” in direct and reverse order thus. “When this cause exists, this effect is; with the arising of this cause, this effect arises. When this cause does not exist, this effect is not; with the cessation of this cause, this effect ceases.”

Dependent on ignorance arise conditioning activities … and so forth.

Thus does this whole mass of suffering arise.

With the cessation of ignorance, conditioning activities cease … and so forth.

Thus does this whole mass of suffering cease.

Thereupon the Blessed One, knowing the meaning of this, uttered, at that time, this paean of joy:

“When indeed the truths become manifest unto the strenuous and meditative brāhmaṇa, then he stands routing the hosts of the Evil One even as the sun illumines the sky.”

Second Week

The second week was uneventful, but he silently taught a great moral lesson to the world. As a mark of profound gratitude to the inanimate bodhi tree that sheltered him during his struggle for enlightenment, he stood at a certain distance gazing at the tree with motionless eyes for one whole week. 53

Following his noble example, his followers, in memory of his enlightenment, still venerate not only the original bodhi tree but also its descendants. 54

Third week

As the Buddha had not given up his temporary residence at the bodhi tree the devas doubted his attainment to buddhahood. The Buddha read their thoughts, and in order to clear their doubts he created by his psychic powers a jewelled ambulatory (ratana-caṇkamana) and paced up and down for another week.

Fourth Week

The fourth week he spent in a jewelled chamber (ratana-ghara) 55 contemplating the intricacies of the Abhidhamma (Higher Teaching). Books state that his mind and body were so purified when he pondered on the Book of Relations (Pahāna), the seventh treatise of the Abhidhamma, that six coloured rays emitted from his body. 56

Fifth week

During the fifth week the Buddha enjoyed the bliss of emancipation (vimutti-sukha), seated in one posture under the famous Ajapāla banyan tree in the vicinity of the bodhi tree. When he arose from that transcendental state a conceited (huhunkajātika) brahmin approached him and after the customary salutations and friendly greetings, questioned him thus: “In what respect, O Venerable Gotama, does one become a brāhmaṇa and what are the conditions that make a brāhmaṇa?”

The Buddha uttered this paean of joy in reply:

“That brahmin who has discarded evil, is without conceit (huhunka), free from defilements, self-controlled, versed in knowledge and who has led the holy life rightly, would call himself a brāhmaṇa. For him there is no elation anywhere in this world.” 57

According to the Jātaka commentary, it was during this week that the daughters of Māra—Taṇhā, Arati and Rāga 58 —made a vain attempt to tempt the Buddha by their charms.

Sixth week

From the Ajapāla banyan tree, the Buddha proceeded to the Mucalinda tree, where he spent the sixth week, again enjoying the bliss of emancipation. At that time there arose an unexpected great shower. Rain clouds and gloomy weather with cold winds prevailed for several days.

Thereupon Mucalinda, the serpent-king, 59 came out of his abode, and coiling round the body of the Buddha seven times, remained keeping his large hood over the head of the Buddha so that he was not affected by the elements.

At the close of seven days Mucalinda, seeing the clear, cloudless sky, uncoiled himself from around the body of the Buddha, and, leaving his own form, took the guise of a young man, and stood in front of the Exalted One with clasped hands.

Thereupon the Buddha uttered this paean of joy:

“Happy is seclusion to him who is contented, to him who has heard the truth, and to him who sees. Happy is goodwill in this world, and so is restraint towards all beings. Happy in this world is non-attachment, the passing beyond of sense desires. The suppression of the ‘I am’ conceit is indeed the highest happiness. 60

Seventh week

The seventh week the Buddha peacefully passed at the Rājāyatana tree, experiencing the bliss of emancipation.

One of the first utterances of the Buddha:

Through many a birth in existence, I wandered,

Seeking, but not finding, the builder of this house.

Sorrowful is repeated birth.

O house-builder, you are seen!

You shall build no house again.

All your rafters are broken. Your ridgepole is shattered.

Mind attains the Unconditioned.

Achieved is the end of craving. 61

At dawn on the very day of his enlightenment, the Buddha uttered this paean of joy which vividly describes his transcendental moral victory and his inner spiritual experience.

The Buddha admits to his past wanderings in existence which entailed suffering, a fact that evidently proves the belief in rebirth. He was compelled to wander and consequently to suffer, as he could not discover the architect that built this house, the body. In his final birth, while engaged in solitary meditation which he had highly developed in the course of his wanderings, after a relentless search he discovered by his own intuitive wisdom the elusive architect, residing not outside but within the recesses of his own heart. It was craving or attachment, a self-creation, a mental element latent in all. How and when this craving originated is incomprehensible. What is created by oneself can be destroyed by oneself? The discovery of the architect is the eradication of craving by attaining arahantship, which in these verses is alluded to as “end of craving.”

The rafters of this self-created house are the passions (kilesa) such as attachment (lobha), aversion (dosa), illusion (moha), conceit (māna), false views (diṭṭhi), doubt (vicikicchā), sloth (thīna), restlessness (uddhacca), moral shamelessness and (ahirika), and moral fearlessness (anottappa). The ridgepole that supports the rafters represents ignorance, the root cause of all passions. The shattering of the ridge-pole of ignorance by wisdom results in the complete demolition of the house. The ridge-pole and rafters are the material with which the architect builds this undesired house. With their destruction the architect is deprived of the material to rebuild the house which is not wanted.

With the demolition of the house the mind, for which there is no place in the analogy, attains the unconditioned state, which is Nibbāna. Whatever that is mundane is left behind, and only the supramundane state, Nibbāna, remains.

V.

The Invitation to Expound the Dhamma

“He who imbibes the Dhamma abides in happiness

with mind pacified.

The wise man ever delights in the Dhamma

revealed by the Ariyas.”—Dhp v. 79

The Dhamma as the Teacher

On one occasion soon after the enlightenment, the Buddha was dwelling at the foot of the Ajapāla banyan tree by the bank of the Nerañjarā river. As he was engaged in solitary meditation the following thought arose in his mind:

Painful indeed is it to live without someone to pay reverence and show deference. How if I should live near an ascetic or brahmin respecting and reverencing him?” 62

Then it occurred to him:

Should I live near another ascetic or brahmin, respecting and reverencing him, in order to bring morality (sīlakkhandha) to perfection? But I do not see in this world including gods, Māras, and Brahmās, and amongst beings including ascetics, brahmins, gods and men, another ascetic or brahmin who is superior to me in morality and with whom I could associate, respecting and reverencing him.

Should I live near another ascetic or brahmin, respecting and reverencing him, in order to bring concentration (samādhikkhandha) to perfection? But I do not see in this world any ascetic or brahmin who is superior to me in concentration and with whom I should associate, respecting and reverencing him.

Should I live near another ascetic or brahmin, respecting and reverencing him, in order to bring wisdom to perfection? But I do not see in this world any ascetic or brahmin who is superior to me in wisdom and with whom I should associate, respecting and reverencing him.

Should I live near another ascetic or brahmin, respecting and reverencing him, in order to bring emancipation (vimuttikkhandha) to perfection? But I do not see in this world any ascetic or brahmin who is superior to me in emancipation and with whom I should associate, respecting and reverencing him.

Then it occurred to him: “How if I should live respecting and reverencing this very Dhamma which I myself have realised?”

Thereupon Brahmā Sahampati, understanding with his own mind the Buddha’s thought, just as a strong man would stretch his bent arm or bend his stretched arm even so did he vanish from the Brahmā realm and appeared before the Buddha. And, covering one shoulder with his upper robe and placing his right knee on the ground, he saluted the Buddha with clasped hands and said thus:

It is so, O Exalted One! It is so, O Accomplished One! O Lord, the worthy, supremely Enlightened Ones, who were in the past, did live respecting and reverencing this very Dhamma.

The worthy, supremely Enlightened Ones, who will be in the future, will also live respecting and reverencing this very Dhamma.

O Lord, may the Exalted One, the worthy, supremely Enlightened One of the present age also live respecting and reverencing this very Dhamma!”

This the Brahmā Sahampati said, and uttering which, furthermore he spoke as follows:

“Those Enlightened Ones of the past, those of the future, and those of the present age, who dispel the grief of many—all of them lived, will live, and are living respecting the noble Dhamma. This is the characteristic of the Buddhas.

“Therefore he who desires his welfare and expects his greatness should certainly respect the noble Dhamma, remembering the message of the Buddhas.”

This the Brahmā Sahampati said, and after which he respectfully saluted the Buddha and passing round him to the right, disappeared immediately.

As the Sangha is also endowed with greatness there is also his reverence towards the Sangha. 63

The Invitation to Expound the Dhamma

From the foot of the Rājāyatana tree the Buddha proceeded to the Ajapāla banyan tree and as he was absorbed in solitary meditation the following thought occurred to him.

“This Dhamma which I have realised is indeed profound, difficult to perceive, difficult to comprehend, tranquil, exalted, not within the sphere of logic, subtle, and is to be understood by the wise. These beings are attached to material pleasures. This causally connected ‘Dependent Arising’ is a subject which is difficult to comprehend. And this Nibbāna—the cessation of the conditioned, the abandoning of all passions, the destruction of craving, the non-attachment, and the cessation—is also a matter not easily comprehensible. If I too were to teach this Dhamma, the others would not understand me. That will be wearisome to me; that will be tiresome to me.”

Then these wonderful verses unheard of before occurred to the Buddha:

“With difficulty have I comprehended the Dhamma. There is no need to proclaim it now. This Dhamma is not easily understood by those who are dominated by lust and hatred. The lust-ridden, shrouded in darkness, do not see this Dhamma, which goes against the stream, which is abstruse, profound, difficult to perceive and subtle.”

As the Buddha reflected thus, he was not disposed to expound the Dhamma.

Thereupon Brahmā Sahampati read the thoughts of the Buddha, and, fearing that the world might perish through not hearing the Dhamma, approached him and invited him to teach the Dhamma thus:

“O Lord, may the Exalted One expound the Dhamma! May the Accomplished One expound the Dhamma! There are beings with little dust in their eyes, who, not hearing the Dhamma, will fall away. There will be those who understand the Dhamma.”

Furthermore he remarked:

“In ancient times there arose in Magadha a Dhamma, impure, thought out by the corrupted. Open this door to the Deathless State. May they hear the Dhamma understood by the stainless one! Just as one standing on the summit of a rocky mountain would behold the people around, even so may the All-Seeing, Wise One ascend this palace of Dhamma! May the Sorrowless One look upon the people who are plunged in grief and are overcome by birth and decay!

“Rise, O Hero, victor in battle, caravan leader, debt-free One, and wander in the World! May the Exalted One teach the Dhamma! There will be those who will understand the Dhamma.”

When he said so the Exalted One spoke to him thus:

“The following thought, O Brahmā, occurred to me: ‘This Dhamma which I have comprehended is not easily understood by those who are dominated by lust and hatred. The lust-ridden, shrouded in darkness, do not see this Dhamma, which goes against the stream, which is abstruse, profound, difficult to perceive, and subtle.’ As I reflected thus, my mind turned into inaction and not to the teaching of the Dhamma.”

Brahmā Sahampati appealed to the Buddha for the second time and he made the same reply.

When he appealed to the Buddha for the third time, the Exalted One, out of pity for beings, surveyed the world with his Buddha-Vision.

As he surveyed thus he saw beings with little and much dust in their eyes, with keen and dull intellect, with good and bad characteristics, beings who are easy and beings who are difficult to be taught, and few others who, with fear, view evil and a life beyond.

As in the case of a blue, red or white lotus pond, some lotuses are born in the water, grow in the water, remain immersed in the water, and thrive plunged in the water; some are born in the water, grow in the water and remain on the surface of the water; some others are born in the water, grow in the water and remain emerging out of the water, unstained by the water. Even so, as the Exalted One surveyed the world with his Buddha-Vision, he saw beings with little and much dust in their eyes, with keen and dull intellect, with good and bad characteristics, beings who are easy and difficult to be taught, and few others who, with fear, view evil and a life beyond. And he addressed the Brahmā Sahampati in a verse thus:

Opened to them are the Doors to the Deathless State.

Let those who have ears repose confidence.64

Being aware of the weariness, O Brahmā,

I did not teach amongst men this glorious and excellent Dhamma.

The delighted Brahmā, thinking that he made himself the occasion for the Exalted One to expound the Dhamma respectfully saluted him and, passing round him to the right, disappeared immediately.65

The First Two Converts

After his memorable fast for forty-nine days, as the Buddha sat under the Rājāyatana tree, two merchants, Tapassu and Bhallika, from Ukkala (Orissa) happened to pass that way. Then a certain deity, 66 who was a blood relative of theirs in a past birth, spoke to them as follows:

The Exalted One, good sirs, is dwelling at the foot of the Rājāyatana tree, soon after his enlightenment. Go and serve the Exalted One with flour and honeycomb. 67 It will conduce to your well-being and happiness for a long time.

Availing themselves of this golden opportunity, the two delighted merchants went to the Exalted One, and, respectfully saluting him, implored him to accept their humble alms so that it may resound to their happiness and well-being.

Then it occurred to the Exalted One: “The tathāgatas do not accept food with their hands. How shall I accept this flour and honeycomb?”

Then the four Great Kings 68 understood the thoughts of the Exalted One with their minds and from the four directions offered him four granite bowls, 69 saying, “O Lord, may the Exalted One accept herewith this flour and honeycomb!”

The Buddha graciously accepted the timely gift with which he received the humble offering of the merchants, and ate his food after his long fast.

After the meal was over the merchants prostrated themselves before the feet of the Buddha and said, “We, O Lord, seek refuge in the Exalted One and the Dhamma. May the Exalted One treat us as lay disciples who have sought refuge from today till death.” 70

These were the first lay disciples 71 of the Buddha who embraced Buddhism by seeking refuge in the Buddha and the Dhamma, reciting the twofold formula.

On the Way to Benares to Teach the Dhamma

On accepting the invitation to teach the Dhamma, the first thought that occurred to the Buddha before he embarked on his great mission was: “To whom shall I teach the Dhamma first? Who will understand the Dhamma quickly? Well, there is Álāra Kālāma 72 who is learned, clever, wise and has for long been with little dust in his eyes. How if I were to teach the Dhamma to him first? He will understand the Dhamma quickly.”

Then a deity appeared before the Buddha and said: “Lord! Álāra Kālāma died a week ago.”

With his supernormal vision he perceived that it was so.

Then he thought of Uddaka Rāmaputta. 73 Instantly a deity informed him that he died the evening before.

With his supernormal vision he perceived this to be so.

Ultimately, the Buddha thought of the five energetic ascetics who attended on him during his struggle for enlightenment. With his supernormal vision he perceived that they were residing in the Deer Park at Isipatana near Benares. So the Buddha stayed at Uruvelā till such time as he was pleased to set out for Benares.

The Buddha was travelling on the highway, when between Gayā and the bodhi tree, beneath whose shade he attained enlightenment, a wandering ascetic named Upaka saw him and addressed him thus: “Extremely clear are your senses, friend! Pure and clean is your complexion. On account of whom has your renunciation been made, friend? Who is your teacher? Whose doctrine do you profess?”

The Buddha replied:

“All have I overcome, all do I know.

From all am I detached, all have I renounced.

Wholly absorbed am I in the destruction of craving (arahantship).

Having comprehended all by myself whom shall I call my teacher?

No teacher have I. 74 An equal to me there is not.

In the world including gods there is no rival to me.

Indeed an arahant am I in this world.

An unsurpassed teacher am I.

Alone am I the All-Enlightened.

Cool and appeased am I.

To establish the wheel of Dhamma to the city of Kāsi I go.

In this blind world I shall beat the drum of Deathlessness. 75

“Then, friend, do you admit that you are an arahant, a limitless Conqueror?” queried Upaka.

“Like me are conquerors who have attained to the destruction of defilements. All the evil conditions have I conquered. Hence, Upaka, I am called a conqueror,” replied the Buddha.

“It may be so, friend!” Upaka curtly remarked, and, nodding his head, turned into a by-road and departed.

Unperturbed by the first rebuff, the Buddha journeyed from place to place, and arrived in due course at the Deer Park in Benares.

Meeting the Five Monks

The five ascetics who saw him coming from afar decided not to pay him due respect as they misconstrued his discontinuance of rigid ascetic practices which proved absolutely futile during his struggle for enlightenment.

They remarked, “Friends, this ascetic Gotama is coming. He is luxurious. He has given up striving and has turned into a life of abundance. He should not be greeted and waited upon. His bowl and robe should not be taken. Nevertheless, a seat should be prepared. If he wishes, let him sit down.”

However, as the Buddha continued to draw near, his august personality was such that they were compelled to receive him with due honour. One came forward and took his bowl and robe, another prepared a seat, and yet another kept water for his feet. Nevertheless, they addressed him by name and called him friend (āvuso), a form of address applied generally to juniors and equals.

At this the Buddha addressed them thus:

Do not, O bhikkhus, address the Tathāgata by name or by the title ‘āvuso.’ An exalted one, O bhikkhus, is the Tathāgata. A fully enlightened one is he. Give ear, O bhikkhus! Deathlessness (amata) has been attained. I shall instruct and teach the Dhamma. If you act according to my instructions, you will before long realise, by your own intuitive wisdom, and live, attaining in this life itself, that supreme consummation of the holy life, for the sake of which sons of noble families rightly leave the household for homelessness.

Thereupon the five ascetics replied:

By that demeanour of yours, friend Gotama, by that discipline, by those painful austerities, you did not attain to any superhuman specific knowledge and insight worthy of an ariya (noble one). How will you, when you have become luxurious, have given up striving, and have turned into a life of abundance, gain any such superhuman specific knowledge and insight worthy of an ariya?

In explanation the Buddha said:

The Tathāgata, O bhikkhus, is not luxurious, has not given up striving, and has not turned into a life of abundance. An exalted one is the Tathāgata. A fully enlightened one is he. Give ear, O bhikkhus! Deathlessness has been attained. I shall instruct and teach the Dhamma. If you act according to my instructions, you will before long realise, by your own intuitive wisdom, and live, attaining in this life itself, that supreme consummation of the holy life, for the sake of which sons of noble families rightly leave the household for homelessness.

For the second time, the prejudiced ascetics expressed their disappointment in the same manner.

For the second time, the Buddha reassured them of his attainment to enlightenment.

When the adamant ascetics refusing to believe him, expressed their view for the third time, the Buddha questioned them thus: “Do you know, O bhikkhus, of an occasion when I ever spoke to you thus before?”

“Certainly not, Lord!”

The Buddha repeated for the third time that he had gained enlightenment and that they also could realise the truth if they would act according to his instructions.

It was indeed a frank utterance, issuing from the sacred lips of the Buddha. The cultured ascetics, though adamant in their views, were then fully convinced of the great achievement of the Buddha and of his competence to act as their moral guide and teacher.

They believed his word and sat in silence to listen to his Noble teaching.

Two of the ascetics the Buddha instructed, while three went out for alms. With what the three ascetics brought from their alms-round the six maintained themselves. Three of the ascetics he instructed, while two ascetics went out for alms. With what the two brought six sustained themselves.

And those five ascetics thus admonished and instructed by the Buddha, being themselves subject to birth, decay, death, sorrow, and passions, realised the real nature of life and, seeking out the birthless, decayless, diseaseless, deathless, sorrowless, passionless, incomparable supreme peace, Nibbāna, attained the incomparable security, Nibbāna, which is free from birth, decay, disease, death, sorrow, and passions. The knowledge arose in them that their deliverance was unshakable, that it was their last birth and that there would be no more of this state again.

The Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, 76 which deals with the four noble truths, was the first discourse delivered by the Buddha to them. Hearing it, Kondañña, the eldest, attained the first stage of sainthood. After receiving further instructions, the other four attained sotāpatti (“stream-winner”) later. On hearing the Anattalakkhaṇa Sutta, 77 which deals with soullessness, all the five attained arahantship, the final stage of sainthood.

The First Five Disciples

The five learned monks who thus attained arahantship and became the Buddha’s first disciples were Kondañña, Bhaddiya, Vappa, Mahānāma, and Assaji of the brahmin clan.

Kondañña was the youngest and the cleverest of the eight brahmins who were summoned by King Suddhodana to name the infant prince. The other four were the sons of those older brahmins. All these five retired to the forest as ascetics in anticipation of the Bodhisatta while he was endeavouring to attain Buddhahood. When he gave up his useless penances and severe austerities and began to nourish the body sparingly to regain his lost strength, these favourite followers, disappointed at his change of method, deserted him and went to Isipatana. Soon after their departure, the Bodhisatta attained Buddhahood.

The Venerable Kondañña became the first arahant and the most senior member of the Sangha. It was Assaji, one of the five, who converted the great Sāriputta, the chief disciple of the Buddha.

VI.

Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta — The First Discourse

“The best of paths is the Eightfold Path.

The best of truths are the four Sayings.

Non-attachment is the best of states.

The best of bipeds is the Seeing One.”—Dhp 273

Ancient India was noted for distinguished philosophers and religious teachers who held diverse views with regard to life and its goal. Brahmajāla Sutta (DN 1) mentions sixty-two varieties of philosophical theories that prevailed in the time of the Buddha.

One extreme view that was diametrically opposed to all current religious beliefs was the nihilistic teaching of the materialists who were also termed cārvākas after the name of the founder.

According to ancient materialism which, in Pali and Sanskrit, was known as lokāyata, man is annihilated after death, leaving behind him whatever force generated by him. In their opinion death is the end of all. This present world alone is real. “Eat, drink, and be merry, for death comes to all,” appears to be the ideal of their system. “Virtue,” they say, “is a delusion and enjoyment is the only reality. Religion is a foolish aberration, a mental disease. There was a distrust of everything good, high, pure and compassionate. Their theory stands for sensualism and selfishness and the gross affirmation of the loud will. There is no need to control passion and instinct since they are the nature’s legacy to men. 78

Another extreme view was that emancipation was possible only by leading a life of strict asceticism. This was purely a religious doctrine firmly held by the ascetics of the highest order. The five monks who attended on the Bodhisatta during his struggle for enlightenment tenaciously adhered to this belief.

In accordance with this view the Buddha, too, before his enlightenment subjected himself to all forms of austerity. After an extraordinary struggle for six years he realised the utter futility of self-mortification. Consequently, he changed his unsuccessful hard course and adopted a middle way. His favourite disciples thus lost confidence in him and deserted him, saying, “The ascetic Gotama has become luxurious, had ceased from striving, and has returned to a life of comfort.”

Their unexpected desertion was definitely a material loss to him as they ministered to all his needs. Nevertheless, he was not discouraged. The iron-willed Bodhisatta must have probably felt happy for being left alone. With unabated enthusiasm and with restored energy he persistently strove until he attained enlightenment, the object of his life.

Precisely two months after his enlightenment on the Ásāḷha (July) full moon day the Buddha delivered his first discourse to the five monks that attended on him.

The First Discourse of the Buddha

Dhammacakka is the name given to this first discourse of the Buddha. It is frequently represented as meaning “the kingdom of truth,” “the kingdom of righteousness,” or “the wheel of truth.” According to the commentators dhamma here means wisdom or knowledge, and cakka means founding or establishment. Dhammacakka therefore means the founding or establishment of wisdom. Dhammacakkappavattana means The Exposition of the Establishment of Wisdom. Dhamma may also be interpreted as truth, and cakka as wheel. Dhammacakkappavattana would therefore mean The Turning or The Establishment of the Wheel of Truth.