Ilankai Tamil Sangam

27th Year on the Web

Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA

The Indo-LTTE War

An Anthology, Part IV

MGR’s Death and the Aftermath

“[MGR] decided to join the army. To qualify for this he learnt horse-riding and the English language through a teacher. Soon he acquired a good knowledge of spoken English with sufficient grammar including active and passive voice. When the time came MGR gave up the idea of joining the army because his chest measurements did not quite come up to the required standard! …”

What was colonial Indian army’s loss in the mid 1930s turned out to be a fortune for Tamil moviedom, Tamil Nadu politics and also to the then budding LTTE.

Part 1 of Anthology

Front Note by Sachi Sri Kantha

That the charismatic film star-turned politician M.G. Ramachandran was the only notable benefactor of the LTTE in its early stages of growth is now recognized as a historical fact. But the reasons for MGR’s patronage of Pirabhakaran and the LTTE in the aftermath of Black July 1983 have been not so crystal clear.

Many reasons, bordering on profound to political expediency, have been alluded to by journalists and analysts (including me) in the past. Here is one more psychological reason which I put forward, that has not been advanced until now. Could it be that MGR saw in Pirabhakaran’s then fledgling army a wish fulfillment which he couldn’t achieve in his illustrious life, when he was young? – that of a military adviser?

How many know the fact that before he made his name in the Tamil movie world, MGR aspired to be an army man, in the then colonial India? But, he gave up on that idea for a technical reason! In January 1981, when I was a delegate at the Fifth International Tamil Research Conference held in Madurai, sponsored by MGR’s then Tamil Nadu government, we received a souvenir entitled ‘Spotlight on Tamil Nadu: Special Publication released on the occasion of The 5th World Tamil Conference’. In this souvenir, there appeared an interview-profile about MGR (pp. 27-31), under the byline Copper Cochin, which I presume is a nom de plume of a foreign journalist. For this profile, MGR had provided some little known secrets of his life in the 1930s as a struggling, bit-part actor. To quote,

“MGR had a long period of being either out of work, or playing very small parts. When the chances of getting cinema roles were becoming bleak he learnt that young people who possess horse-riding training and who can converse in English were being recruited for the army. He decided to join the army. To qualify for this he learnt horse-riding and the English language through a teacher. Soon he acquired a good knowledge of spoken English with sufficient grammar including active and passive voice. When the time came MGR gave up the idea of joining the army because his chest measurements did not quite come up to the required standard! This proved to be his ‘lucky break’ for at this point Nandalal Jaswanthalal, the famous director and editor, offered him his first starring role at the salary of Rs. 350 per month! ‘Halfway through the shooting however, the film folded and I was out of work again,’ said MGR ruefully…”

What was colonial Indian army’s loss in the mid 1930s turned out to be a fortune for Tamil moviedom, Tamil Nadu politics and also to the then budding LTTE. MGR passed away on December 24, 1987, when the Indo-LTTE war had reached 76 days long and counting.

The 11 newsreports and commentaries that appear in this part (in chronological order) predominantly cover the multi-faceted life of MGR, the squabbling which followed his death in Tamil Nadu politics and the pontifications of analysts on how the LTTE would find it difficult to survive the post-MGR phase. That the LTTE has survived for twenty years is a tribute to the leadership of Pirabhakaran, the dedication of his followers as well as to MGR’s foresight.

As one would expect, the newsreports and commentaries that covered MGR’s legendary career were riddled with factual and interpretational errors. Indulgence on ignorance, bias and political spin are some factors which contributed to such errors. The Asiaweek (Hongkong) magazine came out with a cover story on MGR on Jan. 8, 1988. This feature also had its share of factual errors, which prompted me to submit a ‘letter to the editor’. My letter did appear in print, but in a truncated form (with truncations indicated with conventional dots). Now, I don’t have the original version that I sent to the Asiaweek magazine then; for the record, I provide the truncated version that appeared in print, following the Asiaweek’s cover story.

The 11 newsreports and commentaries that appear in this part (in chronological order) are as follows:

Anonymous: ‘Long Live MGR’. Asiaweek, Jan.8, 1988, pp.8-10, with a letter to the editor by Sachi Sri Kantha entitled ‘MGR’s movies’, Asiaweek, Jan.29, 1988.

Anonymous: More carnage. Asiaweek, Jan.8, 1988, p.15.

India correspondent: A Star is Dead. Economist, Jan.9, 1988.

Ron Moreau: Sri Lanka’s Widening War. Newsweek, Jan. 11, 1988, p. 13.

Edward Desmond: Family Affair. Time, Jan.18, 1988, p.11.

Salamat Ali: The Dravidian Factor – MGR’s death throws southern politics in a flux. Far Eastern Economic Review, Feb.4, 1988, pp. 20-21.

Salamat Ali: Across the Palk Strait. Far Eastern Economic Review, Feb.4, 1988, pp. 21-22.

Salamat Ali: Tiger-talk in Madras. Far Eastern Economic Review, Feb.4, 1988, p. 22.

Sam Rajappa: Celluloid hero who became a state’s leading man. Far Eastern Economic Review, Feb.4, 1988, pp. 70-71.

Anonymous: Carving up MGR’s Legacy. Asiaweek, Feb. 12, 1988, p.21.

William Burger: Who Will Succeed MGR? Newsweek, Feb.15, 1988, p.19.

Wherever they appear, dots and words within parenthesis or in italics are as in the originals.

‘Long Live MGR’

[Anonymous; Asiaweek, Jan.8, 1988, pp. 8-10.]

At times, the grief of the crowd seemed almost palpable. Hundreds of thousands of weeping mourners lined the 10 km route of the cortege, in some places standing 20 deep. Many had clambered onto billboards or lampposts to bid a final farewell to their dead anna (elder brother). As the funeral procession departed from the stately Rajaji Hall in Madras, a cry rang out: ‘MGR vazhga’ (‘Long live MGR’). Women beat their breasts and sobbed bitterly as their menfolk picked up the refrain: ‘MGR vazhga, MGR vazhga.’ The body of the man they worshipped as a near-god lay on a spotless white sheet, covered by the flag of India. Still attired in his customary white shirt and dhoti, dark glasses and custom-made fur cap, Maruthur Gopalamenon Ramachandran, chief minister of India’s Tamil Nadu State for more than a decade, was making his final journey.

On the pristine white sands of Marina Beach, the movie star-turned-politician who had captured the imagination of millions of Tamils was buried in a sandalwood casket with gold handles. The black marble slab that covered the grave was just a stone’s throw from the resting place of his political mentor, C.N. Annadurai. Although he had been a Hindu, MGR’s body was not cremated. Some say he was buried according to Christian custom because he died of a heart attack on Dec. 24, just a day before Christmas. Others believe it was because Annadurai, a co-religionist, had also been interred. ‘MGR didn’t leave any instructions,’ said M.P. Paramasivam, a long-time aide to the chief minister. ‘We thought it better to do it this way.’

As the smoke curled upward from a small fire of sandalwood and camphor, the crowd went out of control, pushing hard against a police cordon. Teargas canisters spewed fumes around the grave, but had little effect on the surging mob. Finally, worried about the security of assembled dignitaries, including Home Minister Buta Singh, the police levelled their rifles to restore order. At least twelve people died in rioting across the city; dozens more reportedly committed suicide in grief.

The scene had been equally violent the day before, outside the gates of Rajaji Hall, where MGR’s body had lain in state for a full day. At one point, more than 100,000 screaming, hysterical mourners tried to rush through the doors of the building, demanding to see their beloved leader. The numbers grew to an estimated 1.2 million as more wailing mourners joined the queues. Several women pulled at their hair in grief, others tore off stuck-on red dots on their foreheads in a gesture of mourning for a dead husband. ‘Why should I not weep?’ sobbed Mangayarkarasi, 45, ‘MGR was my brother. He was my father. He was my husband.’

There were few dry eyes among the members of MGR’s All-India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam party who squatted on the steps at the foot of the bier. Jayalalitha Jayaram, an MP and propaganda secretary for the AIADMK, sat at his head, occasionally wiping his face gently with the pallav of her sari. The one-time actress, for whom MGR was rumoured to nurse a secret passion, had earlier been turned away from the Ramachandran residence at the insistence of his widow, V.N. Janaki. Inevitably, some humbug was mixed with the genuine grief. Several people seized the opportunity to be filmed next to the body or to issue statements of condolence.

Though MGR had been ailing ever since a massive stroke and a kidney transplant in 1984, the end was nonetheless sudden. On Dec. 23, he had retired to bed early. At about 11 pm, he woke up feeling nauseous but asked for soup. He had just sipped the last drop when he suffered a heart attack. His personal physician managed to revive him for a short while before he collapsed again. Three specialists then tried cardiac massage; one even ignored the sick man’s bad breath to give him mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Finally in desperation they injected medication straight into the heart to kick it back to life. That, too, failed. Recalls one eyewitness: ‘Every time the doctors tried something, the monitor would start picking up signals [of MGR’s heart], but soon they would weaken. About 1:15 am [on Dec. 24] the signals stopped. It took some time for us to believe he was really dead.’

The news was promptly conveyed to Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in New Delhi. The ruling Congress (I) party is an ally of the AUADMK and is expected to play a pivotal role in deciding MGR’s successor. Besides acting chief minister V. Nedunchezhian, the top contenders are state food minister S. Ramachandran, Jayalalitha and R.M. Veerappan, whom MGR had rehabilitated from disgrace last month soon after the chief minister’s return from medical treatment in the US. Observers say Veerappan has already earned points by praising Gandhi for rushing down to share the Tamilians’ grief.

An AIADMK meeting scheduled for this week will discuss the issue, but highly placed sources told Asiaweek’s Ravi Velloor in Tamil Nadu that for the moment the party had decided to back the interim chief minister. The only problem is that Nedunchezhiyan does not have a mass base. Jayalalitha can pull the crowds, but her elevation would probably be resented by two other Tamil movie star-politicians: Congress (I) MPs Vyjayantimala and Sivaji Ganesan. New Delhi’s choice, however, would likely be S. Ramachandran, who negotiated on its behalf with Colombo for last July’s peace accord aimed at ending Tamil separatism in Sri Lanka.

Indeed, MGR’s death was a grievous blow to the island’s militant Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. MGR had been the Tiger’s godfather, supplying them with refuge and military training in Tamil Nadu. But the militants soon grew out of control in the state, acutely embarrassing their sponsor. Many place a great deal of the blame for Sri Lanka’s current troubles at the chief minister’s doorstep. Finally, Gandhi persuaded MGR to cage the Tigers. After the Indo-Sri Lankan accord was signed, MGR began distancing himself from the militants. Their top leaders were placed under house arrest in Madras. When state police turned down a Tiger leader’s request to lay a wreath at MGR’s funeral, it signalled the end of Tamil Nadu’s support for the Tigers.

Good or bad, the political impact of MGR’s decade was profound. That was something recognised even by Sri Lankan Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa, a virulent critics of the man. In a message of condolence to Janaki, he said: ‘Mr Ramachandran contributed much to South India and its people. His contributions to the people of Sri Lanka, too, cannot be forgotten.’ MGR’s concern for the poor was genuine, perhaps because he keenly remembered his own deprived childhood. Each year, for instance, he would distribute free raincoats to rickshaw pullers in Madras; later he even acted in a sympathetic movie about them, titled Rickshawkaran. The state became the benefactor of the underprivileged. Electricity was subsidised for farmers and school education was made free. In a scheme that benefited some 8.8 million children, state-run schools offered students a free midday meal. The drop-out rate fell.

Even is highly unsuccessful prohibition policy had an altruistic motive: he believed a ban on the sale of liquor would ensure that working class pay packets reached home. Prohibition failed miserably because surrounding states weren’t ‘dry’, thus encouraging liquor smuggling into Tamil Nadu. But when MGR, himself a teetotaller, reluctantly lifted the ban, it was partly to use the revenue from liquor taxes to finance his welfare schemes.

In the eyes of the common people, the chief minister became indistinguishable from the generous-hearted, larger-tan-life heroes he portrayed on screen. Few understood that his welfare schemes, however well-intentioned, were at the expense of developing the state’s infrastructure. Under MGR, Tamil Nadu slipped from second to tenth place among India’s 25 states in industrialisation. By some accounts, MGR virtually ran a police state, aided by his one-time intelligence chief, P.K. Mohandas. Overly centralised administration encouraged inefficiency and corruption. No decision could be taken without the chief minister’s go-ahead.

MGR brooked no challenge to his authority or to his eminence as a Tamil leader – a fact which was brought home firmly to Malaysian Indian Congress President S. Samy Vellu. In early 1987, the MIC chief had travelled to Madras to invite MGR to a world Tamil conference in Malaysia. But he made the mistake of also inviting MGR’s arch-rival, Muthuvel Karunanidhi, leader of the oppositionist Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam. Peeved at being equated with any other Tamil leader, MGR refused to attend the conference.

To his adoring millions, however, the human foibles of Tamil Nadu’s ‘god’ were irrelevant. A combination of his superstar image, the opposition’s blunders and his own personal charisma catapulted MGR to the status of legend. As noted Tamil journalist and playwright Cho Ramaswamy put it: ‘These aren’t days when one expects political leaders to leave a philosophy or message behind them. In MGR’s case, the man was the message.’

Profile: Tamil Nadu’s ‘God’

His Tamil fans knew him by many names: Ponmana Chemmal or ‘Golden-Hearted One’, Makkal Thilakam or ‘Darling of the Masses’, and the one he encouraged in his later years, Puratchi Thailaivar or ‘Revolutionary Leader’. To the teeming millions in Tamil Nadu, Maruthur Gopalamenon Ramachandran was not merely chief minister of the south Indian state. He remained a larger-than-life celluloid hero who never lost a fight and always protected his woman. MGR, they called him fondly.

Interestingly, he was not a Tamil himself, although he tried to obscure the fact. MGR once wrote that his father was a magistrate, but biographers say he was the fifth child of a Sri Lankan tea plantation worker who hailed from Kerala State bordering Tamil Nadu. The actor-turned-politician was born in 1917 in a squalid tea estate ‘line room’ in Kandy. When he died Dec. 24, the people who still live in those dormitories stayed away from work for two days to mourn his passing.

When MGR was only 2, his father died and the family migrated to Tamil Nadu, then known as Madras State. His mother found work as a domestic helper but could not afford to educate her son. MGR was forced to quit school to earn money in a travelling drama troupe. It turned out to be his passport to super-stardom. In the late 1930s, he joined the glittering movie world and became an instant hit as a swashbuckling hero who could expertly fly a plane with his feet while slugging a villain perched on its wing. In a state where people put a high premium on light complexions, MGR’s fair skin helped make him a megastar – he featured in some 160 films.

The Indian National Congress, then fighting against British rule, gave MGR his first taste of politics. After independence in 1947, he was attracted to the secularistic ideals of E.V. Ramaswamy ‘Periyar’ Naicker, who had founded the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam movement in Tamil Nadu. In 1967, DMK leader C.N. Annadurai recruited the film star to contest state assembly polls. When MGR asked how much he should contribute towards the campaign, Annadurai is said to have replied: ‘I don’t need money. Your face is worth millions.’

MGR won, but spent the campaign in a hospital bed after being shot by screen villain and bitter real-life rival, M.R. Radha. Though the bullet damaged his voice permanently, it also heightened his charisma. For a month, thousands kept vigil outside the Madras hospital where he was convalescing. Some 30 people, many of them women, took their own lives in grief.

Five years later, he left the DMK in a huff and formed his own party, the All-India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam. The famous face launched the AIADMK ship with a landslide win in 1977 state assembly polls. But when Indira Gandhi returned to power as prime minister three years later, she sacked the MGR government and helf fresh polls for the state. The one-time matinee idol again proved politically invincible. Yet the years were taking a toll on that million dollar face: his trademark fur cap and dark glasses, it was whispered, were to hide his balding pate and the tell-tale crow’s feet around his eyes. There were other intimations of physical mortality: a massive stroke combined with kidney failure in 1984 left him with seriously impaired speech and movement. Only his immense will power kept him going in the end.

Twice married, MGR had no children. His first wife, coincidentally named Satya like his mother, died of cancer. A few years later, in 1956, he elped with actress V.N. Janaki, who was then still married to film makeup man Ganapathy Bhat. The lovers subsequently wed. In his later years, MGR’s name was linked to one-time co-star Jayalalitha Jayaram, now 39, an MP and AIADMK propaganda secretary. It was well known in Madras, where the Ramachandrans lived, that Janaki deeply resented Jayalalitha. Perhaps not without reason – the buxom young actress is reportedly now threatening to reveal details of secret nuptials with MGR if her position in the party is challenged. Tamil Nadu’s ‘god’, it seems, was only human.

MGR’s movies

[Sachi Sri Kantha; Asiaweek, Jan.29, 1988]

Your profile of the late movie star turned politician M.G. Ramachandran (Jan. 8) is objective, but as a stickler for facts I doubt that he featured in ‘some 160 films’. If I remember correctly, one of the Gemini titles, ‘OLi Vilakku’ (The Light Lamp), billed as MGR’s 100th movie was released in 1968. To have reached 160 he would have acted in seven movies per year for the following eight years, before becoming chief minister of Tamil Nadu in 1977. Too much to expect…Political commitments from 1972 meant fewer movies…He made 120 at most.

You say MGR as ‘an instant hit as a swashbuckling hero’. On the contrary, for almost a decade after his debut in 1936 he played only subsidiary roles. In that period, actors who could sing (for instance, Tyagaraja Bhahavathar and P.U. Chinnappa) held center stage in Tamil movies.

I also question your statement that MGR ‘was not a Tamil himself’. Does identity come only with birth? If that’s so, MGR’s mentor E.V. Ramasamy Naicker wasn’t a Tamil either; he was of Kannada origin. How about Mother Teresa: can she not be identified as an Indian or a Bengali?

More Carnage

[Anonymous; Asiaweek, Jan.8, 1988, p.15.]

It was a bloody end to a bloody year in Sri Lanka. On Dec.27, in the Eastern Province town of Batticaloa, militant Tamil separatists opened fire on policemen in a crowded market, killing one and wounding two others. Coming to their rescue, a dozen officers returned fire. According to a report released by the Indian High Commission in Colombo, they then set alight shops in an angry rage. When the carnage was over, 22 civilians lay dead or dying, and several more wounded.

Four days earlier the country had been rocked by the assassination of Harsha Abeywardene, 37, chairman of the ruling United National Party. He was gunned down by a member of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, an outlawed Sinhalese terrorist group. Abeywardene had been on a tour of the southern districts with President Junius Jayewardene. The area, a hot-bed of Sinhalese nationalism, has been in turmoil since last July, when Jayewardene signed a pact with India aimed at ending the country’s civil strife. The JVP, which opposes the agreement, has been whipping up anti-government sentiment.

During the tour, Abeywardene expressed concern about a police crackdown in the south. ‘He was unhappy that police were harassing youths in the area, driving them into the JVP fold,’ says a party insider. Ironically, after listening to Jayewardene threaten to wipe out the group ‘in two months time’, Abeywardene had told Asiaweek that the president may have been ‘too harsh’ and that an avenue should be kept open for dialogue. ‘Not all these guys are die-hards,’ he insisted.

On Dec.22, the rotund, fuzzy-haired politician returned to Colombo. The following day, as his car turned on to the main road just a few hundred metres from his home, a young man stepped out and emptied a full magazine from a Chinese-made T-56 machine gun into the auto. Abeywardene, his driver, a friend and a bodyguard died at the scene.

Police believe the assassin is a navy deserter who was a crack shot. They say the aim of the murder was to expose the vulnerability of party members. ‘They proved very convincingly that they can kill anyone they want anytime they want,’ says an investigator. ‘Abeywardene was only a symbol.’ To the JVP, perhaps, but to Jayewardene he was said to be like a son. ‘He was neither corrupt, nor ambitious,’ says MP Merryl Kariyawasam. ‘He could have easily been a cabinet minister, but he kept away from such posts for the party’s sake.’

The JVP has used assassinations to try to force party members to resign. Some, however, share Abeywardene’s belief that there should be dialogue with the group. Chief among them is Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa. The president strongly disagrees. ‘It almost appears that Jayewardene is scared that Premadasa may build a power base of his own using the JVP,’ says Sarath Gunewardene, an analyst in Colombo. There are rumours of a widening rift between the two. Jayewardene is now believed to favour Land Minister Gamini Dissanayake as his successor.

In addition to the problems in the south, fighting continues in the north and east. The Indian peacekeeping force in Sri Lanka now comprises some 40,000 troops. Although Delhi claims that its forces rounded up 150 Tamil insurgents and confiscated a large haul of weapons in the northern Jaffna peninsula over the bloody Christmas weekend, peace still appears a long way off.

A Star is Dead

[India Correspondent; Economist, Jan.9, 1988]

The difficulties faced by India’s peace-keeping force in Sri Lanka have been increased by the death in Madras on December 24th of the popular chief minister of the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Mr Rajiv Gandhi’s intervention in Sri Lanka was strongly backed by Mr Marudur Gopalan Ramachandran – MGR, to his political supporters, and to the millions of fans his previous career in films had brought him.

His stalwart support had greatly strengthened Mr Gandhi’s hand last October, when India decided that its troops in the island would have to disarm or neutralise the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. Originally, the Indians hoped they could end the conflict between the Sri Lankan army and the Tigers without getting into a fight themselves. When that hope was frustrated, such was Mr Ramachandran’s personal hold on Tamil Nadu (where his death drove several mourners to suicide) that the sight of Indian soldiers killing Tamils in Sri Lanka aroused little indignation among his state’s vastly more numerous Tamils just across the strait.

With his death, however, India may well find his legacy of personalised rule an awkward one. He left his state’s ruling party, the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, completely leaderless. Within a few days this touched off a struggle that is threatening to tear the party apart. The moving spirits in its warring factions are two women: his widow, Mrs V.N. Janaki Ramachandran; and his party’s propaganda secretary, Miss Jayalalitha Jayaram (also once a popular film star), to whom MGR had been ‘her hero’ and evidently somewhat more.

Mrs Ramachandran is backed by 97 of the party’s 131 members in the state assembly, and has been asked by the state governor to show that she has a majority in the 223-seat assembly by January 24th. Her rival, has the support of some of the party’s most senior members, including the acting chief minister, Mr V.R. Nedunchezhian, and of its general council, 750 of whose 900 members attended a meeting Jayalalitha convened on January 2nd. Jayalalitha owes her strength to the fact that she was second only to Mr Ramachandran as a vote-getter for the party.

Since Mr Nedunchezhian has followed his late leader in declaring full support for India’s policy in Sri Lanka, Mr Rajiv Gandhi’s central government would undoubtedly have preferred to see the Jayalalitha faction win the contest in Tamil Nadu; but Mr Gandhi has wisely held aloof from the fray. Members of his own Congress party hold only 64 of the state assembly’s seats and if Mrs Ramachandran succeeds in establishing her leadership they will have to accept the result.

In the immediate future, there is little likelihood of any shift in the attitude of Mrs Ramachandran’s faction to the Sri Lanka question. If her faction, facing the opposition of the Jayalalitha group, also forfeited the Congress party’s support by turning against the central government’s policy, it would be unable to muster a majority in the assembly. Moreover, all the indications are that most people in Tamil Nadu’s rural areas are still indifferent to what is happening in northern Sri Lanka. In the more political cities opinion is divided, not solidly critical.

India’s problems will worsen, however, if it cannot find a way of subduing the Tigers quickly. If public opinion in Tamil Nadu begins to turn against the Indian military action in Sri Lanka, no new state government will be able to match the late chief minister’s ability to hold the line. This may embolden the Tamil Tigers to go on fighting, at least for a little longer.

Sri Lanka’s Widening War

[Ron Moreau; Newsweek, Jan. 11, 1988, p.13.]

For a while last month it seemed as though Christmas might at last bring a spell of peace to Batticaloa, a predominantly Tamil and Roman Catholic city in Sri Lanka’s strife-scarred Eastern Province. The Indian peacekeeping force, the Sri Lankan police and the Tamil guerrillas of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) were all holding to an informal 48-hour ceasefire. Townspeople packed the cathedral on Christmas Eve, carolers sang in the streets, Santa Clauses passed out presents in the local hospital and fireworks were allowed for the first time since the country’s civil war erupted in 1983.

But the festive spirit was short-lived. Two days after the holiday, gunmen thought to be from the LTTE ambushed three Sri Lankan Sinhalese policemen in the city’s main market, killing one of the officers. Terrified shoppers and merchants jumped for cover. But the dozen or more Sri Lankan police reinforcements who arrived at the scene minutes later were bent on revenge. According to eye witnesses, they indiscriminately grabbed and shot people they found hiding in shops and stalls. They then tossed grenades and firebombs into nearby shops, turning the bazaar into a smoking inferno. At least 25 civilians – many of them Tamils – died in the bloodletting, and some 35 shops were looted and destroyed.

Ethnic violence: Five months after Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Sri Lankan President Junius R. Jayewardene signed the Indo-Sri Lankan peace accord, the ethnic violence continues to flare and India’s worst fear – that its peacekeeping troops would become locked in a quagmire – is being confirmed. If anything, the war is widening. Even as the fighting continues in the north and east, Sinhalese extremists opposed to the peace pact have opened an antigovernment front in the south, assassinating scores of officials and treaty supporters.

Despite India’s best efforts, the LTTE is keeping up its ruthless separatist campaign and still refuses to disarm. Moreover, the Tigers appear to be extending their campaign of intimidation to the country’s Muslim minority. Late last week LTTE rebels killed some 35 Muslim civilians in Kathankudi in the Eastern Province, holding the town virtually captive for 36 hours before Indian troops arrived.

The accord is faring no better in the Sinhalese-dominated southern heartland. There, nationalistic students, along with disaffected and unemployed youths, have joined an outlawed, ultranationalist and violence-prone Sinhalese group, the People’s Liberation Front (JVP), which bitterly opposes the Indian military presence. They oppose the treaty as well, saying that it compromises Sri Lanka’s national soverignty by giving away too much to the Tamils. To torpedo the accord, the student-JVP alliance has launched a brutally effective assassination campaign aimed at eliminating officials and supporters of the president’s ruling United National Party (UNP). Since the agreement was signed, at least 76 government officials and UNP cadres have been killed. In their boldest attack, just before Christmas, two gunmen murdered the UNP’s chairman and key Jayewardene aide, Harsha Abeywardene, in Colombo. And on New Year’s Eve, in what appeared to be another JVP attack, four people were killed and 50 wounded when a bomb exploded during a Buddhist religious procession in the town of Kandy.

Political vacuum: But the biggest battle to save and implement the shaky accord may not be fought in Sri Lanka at all, but in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, across the narrow Palk Strait. The peace prospects suffered yet another serious setback two weeks ago with the death – by natural causes – of M.G. Ramachandran, the powerful and popular chief minister of India’s Tamil Nadu state, who was a key architect of the accord and a vital Gandhi ally.

As chief minister, Ramachandran made the accord possible by using his political prestige and powers of persuasion to convince India’s 50 million Tamils that the accord would protect and promote the rights and interests of Sri Lankan Tamils – despite the hard reality that Indian soldiers were killing scores of Tamils in the Indian offensive against the LTTE. His death not only creates a political vacuum in Tamil Nadu, but may also threaten Gandhi’s ability to maintain support for the agreement at home. There is no guarantee that the state’s new boss will be able to keep his emotional people in line behind Gandhi and the accord. ‘MGR’s death creates a degree of political vacuum in Tamil Nadu,’ says a well-placed Indian official in New Delhi. ‘In such a situation, opponents of the accord might try to stir up trouble.’ There’s little doubt that some will indeed try, but at this point there’s reason to wonder how much more they or anyone could do to undermine the peace.

Family Affair: A widow wins in Tamil Nadu

[Edward W. Desmond; Time, Jan. 18, 1988, p.11.]

In South Asia, as everywhere, family ties can be a potent ingredient of political appeal. India’s Gandhi dynasty provides the most notable example, even as Pakistan’s Benazir Bhutto and Bangladesh’s Begum Khaleda Zia and Sheik Hashina Wazed seek to regain the political heights once occupied by their families. Last week family ties came into play in a political battle in India’s Tamil Nadu state when the widow of M.G. Ramachandran, a former movie idol and for the past decade the state’s charismatic chief minister, was sworn in as his successor.

The choice of Janaki Ramachandran, 64, a onetime actress turned housewife who had previously eschewed politics, deepened a split in the state’s ruling All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam Party. One faction lined up behind Janaki, the other behind Jayalalitha Jayaram, 39, another movie actress, who had moved into politics in 1982 and in recent years was a close associate of the late chief minister. The rift threatened to inflame divisive issues in the state and no doubt troubled Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, who relied on the popular Ramachandran’s authority to cool hot heads among the state’s nearly 50 million ethnic Tamils. Some of the more militant Tamils favor all-out support for the Tamil guerrillas in Sri Lanka, who are fighting both President Junius R. Jayewardene’s troops and Indian peacekeeping forces.

For ten years Ramachandran, sporting his trademark sunglasses and white fur hat, dominated Tamil Nadu as the head of the AIADMK, but he failed to arrange for an orderly succession. After he died of a heart attack at age 70 three weeks ago, the ambitions of his lieutenants surfaced even as his body lay in state. Jayalalitha, who starred as Ramachandran’s love interest in more than 20 films before going into politics and eventually becoming his party’s propaganda secretary, staged a dramatic 21-hour vigil by the chief minister’s body while his widow was nowhere to be seen. Janaki’s family was enraged. When Jayalalitha tried to climb onto the gun carriage transporting the former chief minister’s body to the funeral, a nephew of Janaki’s actually knocked her off the bier. ‘A very small group of people,’ a bruised Jayalalitha said later, ‘was determined to see that I was nowhere near the body of my beloved leader.’

Nowhere near the seat of power either. An opposing party faction persuaded Janaki to stand for her husband’s post. Jayalalitha meantime decided to drop her own ambitions for the chief minister’s position and instead back V.R. Nedunchezhian, 67, the senior-most member of Ramachandran’s cabinet.

The key to victory would be majority backing of the 131 AIADMK state assemblymen. For several days both sides wooed, threatened and allegedly even bribed and forcibly detained legislators to secure their support. Early last week the Janaki group gained the upper hand. Three buses loaded with 97 AIADMK legislators who claimed to be supporting Janaki pulled up at the residence of S.l. Khurana, the governor of Tamil Nadu. After interviewing each one, the governor declared that he ‘was satisfied that the 97 [representatives] who had voted for Janaki did so on their own volition.’ Late last week he swore in Janaki and her cabinet.

Gandhi stayed out of the fray, although Janaki’s elevation was probably the best outcome he could hope for. In an attempt to reassure New Delhi, the new chief minister reiterated her late husband’s dedication to ‘national unity and integrity’ and ‘full implementation’ of the Indo-Sri Lankan accord to end the insurgency on the island.

Nedunchezhian’s bid for power is not dead. Within three weeks of Janaki’s swearing-in, all 223 members of the state assembly will vote on the new government; in the meantime both factions are continuing the struggle to win over their opponents. [reported by K.K. Sharma/ New Delhi]

The Dravidian Factor: MGR’s death throws southern politics in a flux

[Salamat Ali; Far Eastern Economic Review, Feb. 4, 1988, pp. 20-21]

The death of M.G. Ramachandran, the chief minister of Tamil Nadu, has unsettled the politics of this south Indian state. The film star-turned-politician who was popularly known as MGR rode to power on the back of the ethnic Dravidian movement, but became an ally of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and supported New Delhi’s policy on Sri Lanka. Thus the repercussions of his death will also be felt in India’s national and foreign policies.

Waiting in the wings to recapture power in the state is the opposition party, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) led by M. Karunanidhi. MGR split with the DMK to form his All India Anna DMK or AIADMK in 1972 and became chief minister five years later. If the factional squabbling in the ruling party precipitates a snap election, the opposition DMK could well come back to power in the state. In that event, given the DMK’s deep antagonism towards New Delhi and the Congress Party, the latter’s political hopes in southern India could well be frustrated.

DMK is a cadre-based party and its tight-knit organisation is considered as good as that of the communists and the right wing Hindu fundamentalist groups. Although it lost the last state election in December 1984, its margin of defeat in almost all seats was less than 3% of the votes polled. This performance was all the more remarkable because it was scored against a wave of ‘double sympathy’ – MGR had been paralysed by a stroke and prime minister Indira Gandhi had been assassinated a couple of months earlier.

In a state where the electorate has traditionally responded more to charismatic personalities than to party platforms, Karunanidhi is now the only political leader of any stature. Also, he is the foremost opponent of India’s policy on the ethnic Tamil crisis in Sri Lanka, as well as the strongest exponent of the Dravidian political philosophy which has strong overtones of linguistic and racial chauvinism.

In practice, the DMK’s politics hinges on opposing the national language of Hindi and the dominance of upper castes among Hindus, especially in northern India. The anti-north sentiments are usually expressed as the domineering Aryan north’s insensitivity towards the Dravidian south.

However, most of the Congress leaders and some political analysts in the state maintain that the Dravidian movement is dead. The movement was born as a reaction against the supremacy of the Tamil Brahmin caste. The prolonged agitation against the upper castes and two decades of DMK and AIADMK rule have reduced the Brahmins to underdogs who no longer pose any social or political threat.

To Ramaswamy Naicker, the spiritual mentor of the Dravidian movement, the corollary to opposing the priestly Brahmin caste was atheism. But the hold of religion is such that today most of the movement’s leaders routinely go to temples. Moreover, they have come to terms with the importance of Hindi in national life and are sending their children to elite private schools which teach Hindi, while the state-run schools Tamil Nadu continue to ban Hindi. Analysts, including Congress leaders, also maintain that the decade of MGR’s rule has brought the Tamil masses into the national mainstream and the anti-north sentiments have lost their sting.

Such an appreciation of the political situation should propel the Congress to try to wrest control in Tamil Nadu. But the Congress has chosen to wait on the sidelines for the time being. For the past decade it relied on MGR to make electoral gains in the state, primarily by bargaining for a share of the state’s seats in parliament. MGR’s critics charge that initially he needed the Congress to defeat the DMK, and later became vulnerable enough to concede to most of the Congress’ demands.

MGR hated Karunanidhi with an intensity that would have forced him to align with anyone who was against his arch foe. The antipathy was as much personal as political, and dates back to the 1960s when the late C.N. Annadurai was the party leader. MGR was already a popular film star before joining the party and Annadurai, himself a popular writer and orator, carefully built up MGR’s movie image into a political asset.

Ironically, rural electrification, which got a boost in the late 1950s and early 1960s when Congress leader K. Kamaraj was the state’s chief minister, led to more movie houses in the rural areas and MGR’s films that brought DMK propaganda to the state’s countryside.

Annadurai built MGR into the mould of a Lone Ranger ready to rescue every underdog, showering bounties on the needy and putting down all tyrants and villains. His popularity on the screen became a political crowd-puller on the streets, and all over Tamil Nadu MGR fan clubs proliferated. After Annadurai’s death in 1969, Karunanidhi succeeded him as chief minister and correctly sensed the threat to his power from the MGR fan clubs and ordered the actor to wind them up. Seeing it as an attempt to clip his wings, MGR revolted and formed his own party.

After his success in the 1977 state elections, MGR emerged as a political leader in his own right and showed an uncanny appreciation of policies which could bring him maximum popular support. The AIADMK’s ideology was called ‘Annaism,’ after Annadurai, and described as a combination of capitalism, socialism and communism – a sort of populism also dubbed ‘the dole raj’. He built public lavatories; distributed clothes to widows and found jobs for them. He provided free meals to poor schoolchildren who otherwise would have gone hungry and provided raincoats to all pedicab drivers in Madras and elsewhere.

Basically, his style was to give the needy more than they expected – he often dug into his own pockets but always made sure that his philanthrophy became widely known. Therefore, no charge of corruption against himself or his regime could ever stick. His fans argued that he was taking from the rich to give to the poor – an action in line with the heroes he played in the films.

His political inheritance is contested between two factions both headed by women. One faction is led by 38 year-old Jayalalitha Jayaram, a movie heroine who became the party propaganda chief and was close to MGR both on screen and off. A second faction is headed by MGR’s widow, Janaki. Soon after MGR’s death, the senior most cabinet minister, V.R. Nedunchezhian, was sworn in as acting chief minister.

When Janaki’s followers paraded 97 of the 131 AIADMK legislators before the state’s governor, she was allowed to form the government and prove her majority in the legislature when it is convened. While the show of strength between the two rivals was looming, the Jayalalitha group herded its 47 legislators together and took them out of the state to prevent any defections to the opposite camp. On its part, the Janaki group, in order to encourage such defections, threatened the seven ministers in the rival camp with expulsion from the party and the legislature.

Janaki needs the support of 112 of the 223 state legislators to prove her majority. She needs the backing of defectors from the Jayalalitha faction or from the 64 members the Congress party commands. More worrisome for both Congress and the AIADMK, however, is the strategy of the DMK which has been patiently watching the political wrangle in the expectation that the two factions would destroy one another.

On 19 January, DMK chief Karunanidhi predicted that the Janaki government would collapse, leading to direct central rule over the state and followed by fresh elections by the end of the year.

Across the Palk Strait

[Salamat Ali; Far Eastern Economic Review, Feb. 4, 1988, pp. 21-22]

For the first time since India’s independence, the internal politics of one of its states – Tamil Nadu – has become inextricably entangled with the country’s foreign relations. One of the major concerns facing New Delhi is whether the tacit acceptance in Tamil Nadu of Indian military operations in Sri Lanka will continue amid the war of succession ranging in the state after the death of chief minister M.G. Ramachandran.

The ethnic Tamil conflict in Sri Lanka has been a matter of abiding concern in Tamil Nadu, where the people share linguistic and religious ties with their brethren on the island nation. In recent years, as the conflict escalated, a large number of refugees fled to Tamil Nadu, which had also given sanctuary to militant Sri Lankan groups. Under the July 1987 Indo-Sri Lankan peace accord, Indian troops were sent to Sri Lanka to enforce peace in the Tamil regions there and became involved in clashes with armed militants.

The charismatic Ramachandran, popularly known as MGR, had managed to contain the disaffection in his state, in the wake of allegations of the army’s excesses against Sri Lankan Tamils. It is widely accepted that but for MGR’s efforts New Delhi would have gound it extremely difficult to sell its Sri Lanka policy to Tamil Nadu. However, while supporting New Delhi’s policies, MGR continued to back the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), the largest Sri Lankan militant group, much to the dismay of the Indian Government. Understandably, New Delhi wants the next administration in Tamil Nadu to support its policy on Sri Lanka.

A significant section of opinion among intellectuals and Congress leaders in Tamil Nadu favours a more aggressive espousal of the Sri Lankan policy. Cho Ramaswamy, editor of the Tughlak weekly and a widely read commentator on the state’s politics, argues that opposition to the Sri Lanka policy is ‘a played-out card’ in the state’s electoral politics. K. Ramamurthy, a Congress MP from the state, also expressed similar views to the REVIEW.

However, there is continuing concern in India over Tamil Nadu’s feelings about Sri Lanka. In a message on the eve of Army Day in mid-January, Gen. K. Sundarji, India’s chief of the army staff, called for a national consensus on the Indian army’s operations in Sri Lanka. Regretting doubts and reservations in quarters he did not identify, the general pointed out that these could affect the morale of his men.

C. Aranganayagam, a leader of the Jayalalitha faction of the ruling AIADMK – MGR’s party – and Tamil Nadu education minister until MGR’s death concedes that feelings ran high in the state over the reports of the Indian army’s killings in Jaffna, but he adds that this was primarily because the army was assigned a law-and-order role which should have been played by the police. According to him, public opinion in Tamil Nadu strongly favours a fair deal for fellow Tamils in Sri Lanka but does not like a division of that country. He does not believe that the Tamils in India could be alienated from the national mainstream over this issue.

But the rival faction controlled by MGR’s widow, Janaki, and the opposition DMK dismiss the Jayalalitha group as a ‘pet poodle’ of New Delhi. Valampuri John, an MP from Tamil Nadu and an influential leader of the Janaki faction, told the REVIEW that the Indo-Sri Lankan accord was an ineffectual agreement for it lacked the participation of the two key elements to the ethnic conflict: the majority Sinhalese and the minority Tamils or their representatives. On the feelings in Tamil Nadu, John said that the psyche of the Dravidians – the people who ethnically dominate in the south – was deeply wounded by the Indian army’s actions, and the seeds of resentment could sprout at the next opportunity.

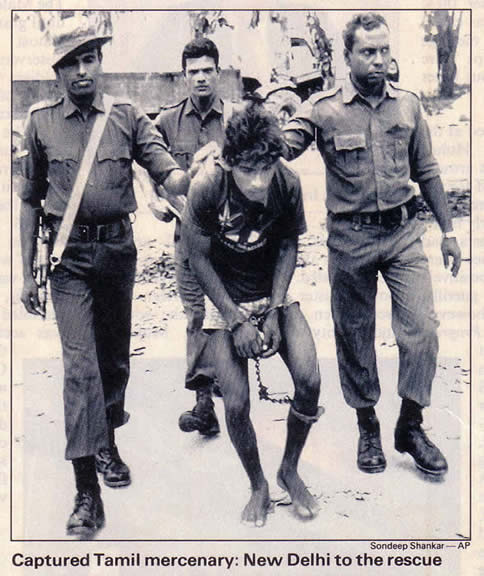

There was an upsurge of sympathy for the plight of Sri Lankan Tamils after the ethnic riots in Colombo in 1983, following which large numbers of refugees moved across the Palk Strait into Tamil Nadu, as did all the armed separatist groups of Sri Lankan Tamils. Among the several militant groups, the Tamil Eelam Liberation Organisation (TELO) headed by Sri Sabaratnam was the principal beneficiary of New Delhi’s patronage, including military training and supplies. However, the largest and the best organised of the groups was the LTTE, which was not actively backed by the Indian Government. In early 1986, the LTTE killed Sabaratnam and nearly decimated the TELO leadership. After that, New Delhi began supporting other smaller guerilla groups also.

Because the TELO was supported by Karunanidhi and was hostile to the LTTE, the latter was chosen by MGR for his patronage. As a result the LTTE acquired a special status in Tamil Nadu, freely importing arms and building up weapons’ stockpiles. The LTTE also threw in its lot fully with MGR and his party. When the DMK workers collected some money on Karunanidhi’s birthday for distribution among the militant groups, the LTTE refused to receive its share and instead bagged a gift from MGR which was five times as big. This was taken as an affront to Karunanidhi and more so to the entire DMK organisation.

MGR also persuaded New Delhi that because of its size the LTTE should not be totally ignored. In carrying out New Delhi’s instructions on the militant groups, MGR went far beyond his brief in the local handling of the LTTE. However, the central government did not consider it prudent to antagonise MGR over the issue of his special favours to the LTTE.

When Sri Lankan President Junius Jayewardene made Colombo’s participation in the 1986 Bangalore summit of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation conditional upon the disarming of Tamil militants sheltering in India, MGR helped New Delhi in seizing all the rebels’ weapons. But what has remained unpublicised is that he later returned all the seized arms, including those belonging to other groups, to the LTTE.

When MGR learned that the July 1987 Indo-Sri Lankan peace accord was nearing completion, he tipped off the LTTE which moved most of its arsenal to secret hideouts in northern Sri Lanka. MGR also told the LTTE that all militant groups would be disarmed by the Indian Peace-Keeping Force, so they too hid their arms, which later had to be searched out by the Indian troops after a prolonged campaign.

Although the LTTE has been engaged in combat with Indian troops since October, MGR kept his close links with it. His statements on India’s Sri Lanka policy were deliberately vague enough to yield differing interpretations by the LTTE and New Delhi. Until MGR’s death, the LTTE’s speedboats used to shuttle between Tamil Nadu and Jaffna’s northern coast with impunity almost every night.

New Delhi might now try to break the LTTE’s special links with the Tamil Nadu regime. But the LTTE has learned to play politics with the major parties in the state and is striving to retain the close ties with MGR’s successor and widow, Janaki, while opening up their channels with the opposition DMK as well.

Six months after Indian troops landed in Sri Lanka, the conflict has continued to fester with no sign of an early end to the military campaign. In addition, the insurgency in southern Sri Lanka by Sinhalese extremists has frustrated Colombo’s plan to restore normalcy to the country. If the LTTE and the southern subversives combine their efforts, Colombo would be under greater pressure and this would make a political solution almost impossible. The impact of these events will further unsettle Tamil Nadu’s politics.

Tiger-talk in Madras: The LTTE stick to its guns

[Salamat Ali; Far Eastern Economic Review, Feb. 4, 1988, p.22.]

For the past six months the Indian Peace-Keeping Force (IPKF) has been trying hard to restore normalcy to the strife-torn northern and eastern regions of Sri Lanka under an accord signed with Colombo in July last year. The Indian troops went in to protect the interests of the ethnic Tamil minority of Sri Lanka and have been locked in heavy clashes with the largest separatist group, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), which has not accepted the peace accord.

But the murky politics of the Subcontinent is such that despite the heavy Indian casualties at the hands of the LTTE, the latter continues to be politically active in the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu, where it has sought shelter for the past several years. The LTTE headquarters in the Tamil Nadu capital of Madras, though surrounded by police and inaccessible to reporters, continues to function.

The LTTE, which had been heavily patronised by Tamil Nadu chief minister M.G. Ramachandran – popularly called MGR – adopted a low profile after his death on 24 December last year. But soon after MGR’s widow, Janaki, succeeded him in early January, the Madras headquarters of the LTTE issued a statement in the name of its political department denouncing Sri Lankan President Junius Jayewardene’s government as a racist regime and the Indian Government as its collaborator.

Further, it described India as ‘a colonial power out to suppress the aspirations of the Tamils.’ The statement also threatened the Sri Lankan civil servants, who reported for duty in the Tamil regions of the country to help restore normalcy under Indian aegis, with ‘dire consequences’ as they were deemed to be traitors to the Tamil cause.

Through some local intermediaries, this correspondent managed to get an interview with a spokesman of the LTTE in Madras. Identified only as Mr Rao, a common surname in Tamil Nadu, he explained his group’s views on the Sri Lankan situation:

There is ample popular support for the LTTE in the northern and eastern regions of Sri Lanka – the majority Tamil areas – contrary to the assertions of the IPKF.

The Indian strategy of choking off guerilla supply lines will not succeed, because the LTTE has other sources of replenishment. The arms caches seized by the IPKF are treated by the LTTE as normal losses in a war and the group has provided for such contingencies.

The LTTE is not a party to the Indo-Sri Lankan peace accord. The LTTE leaders were taken to New Delhi from Madras for consultations only after the accord was finalised. In their consultation with Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, they were shown the accord, but not even a copy of it was given to them.

The Northern and Eastern provinces are the traditional homeland of the Tamils in Sri Lanka and the LTTE will not surrender any part of this homeland.

The LTTE stands for Eelam – an independent Tamil homeland – as well as peace. For the sake of peace the LTTE can accept an interim settlement short of Eelam. But after such a settlement, it will continue to struggle for its own state, though peacefully.

*

Celluloid Hero who Became a State’s Leading Man

[Sam Rajappa; Far Eastern Economic Review, Feb. 4, 1988, p. 70-71.]

Marudur Gopalamenon Ramachandran, a non-Tamil who ruled Tamil Nadu for 10 years like a medieval potentate until he died on 24 December at the age of 70, was one of the most extraordinary phenomena in modern Indian history. More than 2.5 million people from all over the state turned up in Madras to pay homage to a person whom they had come to regard as a Superman.

The people seemed pulled more by some gravitational force than by any compelling sense of grief. More than 50 people, including a 12 year-old school girl, committed suicide either by self-immolation, hanging or consuming poison. A few died of heart attacks as a pall of gloom enveloped the state on that Christmas Eve when news spread of the death of MGR.

For the 4 million-odd people of the metropolitan city of Madras, it was a terrifying experience. Law and order seemed to have died with MGR, at least until his body, encased in a sandalwood coffin, was lowered into his grave on the Marina Beach, next to that of his mentor, C.N. Annadurai, on Christmas Day. As mourners filed past his body, laid out at Rajaji Hall, which during the British Raj had served as a gubernatorial banquet hall, the situation in the city deteriorated with thugs and vandals ransacking shops, looting whatever they could lay their hands on, and breaking everything that was breakable.

A bronze statue of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) leader, M. Karunanidhi, on the busy Mount Road barely 200 m from Rajaji Hall, was smashed. There were more instances of drunkenness in Madras on that Christmas Eve than ever before in this 300 year-old city. Liquor shops became the prime target of vandals. Although the situation in New Delhi was much worse when Indira Gandhi was assassinated, at least her funeral was conducted with great dignity and decorum. MGR’s funeral turned into a festival.

MGR came from very humble origins. Born in Kandy, Sri Lanka, in 1917 (officially at least), he had to quit school after the third form in order to support his family – by taking bit parts in productions by a touring theatrical troupe. A sense of the dramatic was probably inculcated in him early on, as was shown in later years. His efforts brought him to the glamorous world of films where he worked hard to maintain the hero image he had created.

In 1967 MGR entered politics when he was recruited into the DMK by Annadurai. But while he was hailing the latter as his mentor, he was saying the late Kamaraj of the Congress Party was his ultimate leader. This duality found expression in all he had said and done. He proclaimed himself a staunch nationalist even while being the leading player in the Dravidian movement which set in a trend of separatism unmatched until the Sikhs raised their heads for Khalistan. His histrionics and antics on screen swayed an uncritical public.

Having tasted the heady sense of adulation, MGR slowly built up his personal stock while in the DMK. He created the image of an action hero who used his fists more than his tongue. He showed the masses through his films the importance of fighting to help themselves. When he became chief minister of Tamil Nadu, he asked his party men to carry knives for self-protection.

On screen MGR was the typical man of the Tamil Nadu lower classes. He took the parts of rickshaw-puller, taxi driver, fisherman, farmer and so on. And in all these films, the moral character of the hero remained unchanged. Always facing social opposition, he was honest and hardworking. Thus, he invited the masses to identify with him. And when people found the hero overcoming the same social problems they faced in real life, their attachment to MGR became very real and personal.

MGR never championed any cause in his films that could hurt the feelings of any social group or community. He did not, however, hesitate to use the medium to attack Karunanidhi, who became his political enemy after the DMK split in 1972. He devoted a whole film, Namnadu, to castigating Karunanidhi’s DMK government. But he never sought to mobilise public opinion against social injustices. Nevertheless, people began to think the person they wanted as their leader was not someone like MGR, but MGR himself.

Having endured hunger, poverty and squalor in his boyhood, MGR knew how to identify with the have-nots. When he parted company with the DMK and launched his All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) in 1972, the established politicians failed to grasp the implications of the move. Within five years, the party was voted to power in the state, solely on the popularity and personal image of MGR.

He soon proved that he was as shrewd a politician as he was a successful film star by winning the subsequent state assembly elections in 1980 and 1984, the last one from his hospital bed in Brooklyn, New York, where he was undergoing a kidney transplant. As chief minister, he tried to bring his film image to life. Feeding poor school children and the aged, distributing clothes and caring for the destitute, he earned from the masses an affection bordering on worship. But in terms of economic development, Tamil Nadu slid down a slippery slope under his decade of stewardship.

As MGR became ever more popular, he began distancing himself from the public. He considered himself a repository of all that was good and consolidated his following by publicised philanthrophy. In the people’s eyes he was a god, and consequently he became more autocratic. Increasingly, he receded behind his dark glasses and makeup, hiding his age. He shunned the press and prevented his ministers and officials from meeting journalists.

Although his speech was seriously impaired following a stroke three years ago, and his health was deteriorating, MGR never thought of stepping down or nominating a successor. It had been his long-cherished wish to die in office. But his legacy could not endure. Cracks appeared in the structure of the AIADMK even as his body was being placed on a gun carriage for its final journey. Jayalalitha, who had co-starred with him in several films, and whom he had groomed as his political heir, was abused and kicked in full view of the public. The monolith the AIADMK had been during the past 15 years, crumbled with the death of MGR, its founder-leader, the likes of whom we may never see again.

Carving Up MGR’s Legacy

[Anonymous; Asiaweek, Feb. 12, 1988, p.21]

India’s Tamil Nadu State had never seen anything like it. A month after late chief minister and movie idol Maruthur Gopalamenon Ramachandran, popularly known as MGR, was buried, politicians were literally at each other’s throats. Chairs, microphones, pedestal fans and paperweights were hurtled across the room during a state assembly session in Madras on Jan. 28, leaving about 30 legislators injured. Police were called in to break up the fight. ‘If the police had not come in,’ said Speaker Paul Hector Pandian, ‘even murder would have taken place.’ Two days later, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi sacked the 24 day-old government and placed the state under president’s rule.

The fracas was the result of factionalism within MGR’s All-India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK). Competing for power are two women close to the late leader: his widow V.N. Janaki, 62, and party propaganda secretary Jayalalitha Jayaram, 39, for whom MGR was rumoured to have nursed a secret passion. Convinced that Janaki had majority backing, Governor S.L. Khurana appointed her chief minister on Jan. 3. When the house met for a vote of confidence on the new government, tensions were high. Speaker Pandian aggravated the situation by disqualifying six Jayalalitha supporters from voting. The free-for-all broke out when rebellious legislators tried to oust him. The 234-member house reconvened fifteen minutes later with substantially reduced numbers and passed the confidence motion 99-8. Then came New Delhi’s action.

Fresh polls to the state assembly are to be held as soon as possible. Although India’s ruling Congress (I) party, which supports AIADMK, sought to remain neutral in the dispute, observers reckon it is now likely to side with Jayalalitha’s faction. But by backing her, Congress (I) has lost a superstar within its own ranks: Sivaji Ganesan. The party stalwart, whose popularity is second only to MGR’s in Tamil Nadu, was clearly nettled by the prospect of Jayalalitha ascending to power. He may now support the Janaki faction, setting the stage for growing anti-Delhi sentiment.

There is already evidence of such a trend. Unlike other opposition groups, AIADMK’s chief opponent, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam led by former chief minister Muthuvel Karunanidhi, did not boycott the legislative assembly session after the punch-up. Although its members voted against the Janaki government, their presence drew praise from Pandian, who said only those with a Dravidian, or southern ethnic, background could rule the state. His words could foreshadow an ironic future alignment between MGR’s bitter rival Karunanidhi and his widow Janaki.

Until polls are held in Tamil Nadu, the state will be administered by President Ramaswamy Venkataraman. A Tamil, Venkataraman has been accused of meddling in his home state’s politics. Critics claim he helped Janaki form her government even though her rival appeared to have a larger grassroots following. Analysts say he may be in danger of falling out of favour with the prime minister.

Who Will Succeed MGR?

[William Burger, Newsweek, Feb. 15, 1988, p.19.]

When M.G. Ramachandran died in his sleep last Christmas Eve, the Indian state of Tamil Nadu lost more than a chief minister – it lost all semblance of order. For 10 years the man Indians knew simply as MGR had run the volatile southern state of 50 million with an air of independence and a close political rapport with the Gandhis and their ruling Congress Party. What MGR didn’t do was provide for his succession, and his death at age 70 set off a bizarre power struggle that has already spread to New Delhi and that ultimately may threaten India’s efforts to bring peace to nearby Sri Lanka.

It is a battle more of personalities than of politics. MGR had been a film star in India before he turned politician, and his death set off a furious row between two women who were close to him: his widow, retired actress Janaki Ramachandran, 64, and Jayalalitha Jayaram, 38, another actress who starred opposite MGR in several hit films and whose name has been linked to his off-screen as well. The carping between them began even as MGR’s body was lying in state in Madras. Jayalalitha, whom MGR had appointed as his party’s propaganda secretary and who represented the party in India’s Parliament, insisted that she stand next to the body of her ‘beloved leader,’ after which Janaki’s supporters tried to eject her from the building.

Soon Janaki and a candidate backed by Jayalalitha began campaigning to succeed MGR as chief minister, and at first it appeared that Janaki might win handily. She had the endorsement of 97 of the 131 members of the assembly from MGR’s dominant All-India Elder Brother Dravidian Progressive Party, and Rajiv Gandhi sent out signals that he backed the widow’s bid for power. But late last month Gandhi suddenly switched sides, apparently believing that Jayalalitha’s camp would be more willing to include his Congress Party in a coalition government. When the leadership vote came, the rancorous mood on the floor of the state assembly spawned an all-out brawl. Legislators began fighting and throwing ashtrays at one another. Some wrenched microphones from their desks to use as clubs. In the end, helmeted police had to be called in to restore order. At least 30 assembly members were hurt in the embarrassing fracas. Somehow amid the confusion a vote was taken, and though Janaki captured only 99 votes – 13 short of the majority needed – one of her supporters, declared her the winner.

‘Great betrayal’: That was too much for Gandhi. Two days later the prime minister dissolved the state government and put New Delhi in charge of Tamil Nadu’s affairs – at least until a new election can be held within six months. Janaki’s camp called Gandhi’s takeover a ‘great betrayal’ that, according to one of her aides, ‘Tamils will never forgive.’

Gandhi’s handling of the affair may well backfire. Though he can now spend the next six months trying to team up with Janaki, Jayalalitha or another Tamil leader, his sacking of the state government is rekindling Tamil chauvinism, and it may give courage to opposition parties that have strongly opposed India’s Sri Lanka policy, which has pitted 40,000 Indian troops against ethnic Tamil rebels in that country. Now even Janaki, whose husband strongly supported the Indo-Sri Lanka peace accord, is asking Gandhi to ‘restrain’ the Indian troops from ‘attacking innocent Tamils’ in Sri Lanka. Gandhi runs the clear risk that his domestic political machinations will undercut his most admired diplomatic initiative.

Continued…Part V

The Indo-LTTE War

An Anthology, Part V

Brewing Discontent with Rajiv and Sonia Gandhi

January 8, 2008

The first item in this part 5 authored by Saeed Naqvi…provides a background-summary to the Rajiv – V.P. Singh split in 1987. The wheel of political fortune would turn towards Singh, who would eventually succeed Rajiv as the Indian prime minister in late 1989. As Naqvi concluded his commentary, by the end of 1987, “With the Left and the Right vying for [V.P.]Singh’s support and Gandhi’s grip on the middle ground rapidly weakening, India’s political future promises some interesting twists.” When 1988 dawned, what Rajiv and his Congress Party panderers yearned for was a quick victory for the Indian army against the LTTE in Eelam.

Part 1 of series

Front Note by Sachi Sri Kantha

The 9 news reports, commentaries and interviews that appear in this part (in chronological order) predominantly cover two themes; (1) brewing discontent on Rajiv and Sonia Gandhi in early 1988, and (2) the tug of war for Jayewardene succession among the four UNP contenders amidst the ascent of JVP terrorism in the southern Sri Lanka. These were the sub-plots which exerted influences on the progress of the Indo-LTTE war. In chronological order, these 9 news reports, commentaries and interviews are as follows:

Saeed Naqvi: The Many Faces of V P Singh. South (London), Nov.,1987.

Marguerite Johnson: Caught in the Bloody Middle. Time, Jan. 11, 1988, p. 25.

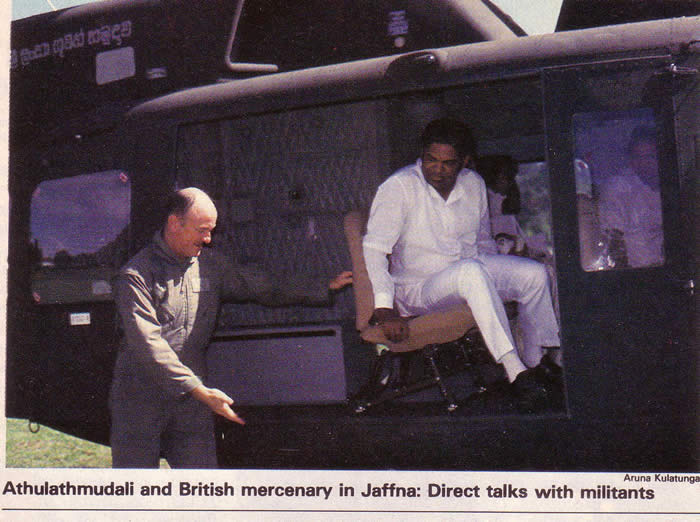

Manik de Silva: Militants and Ministers. Far Eastern Economic Review, Jan. 14, 1988, p. 34.

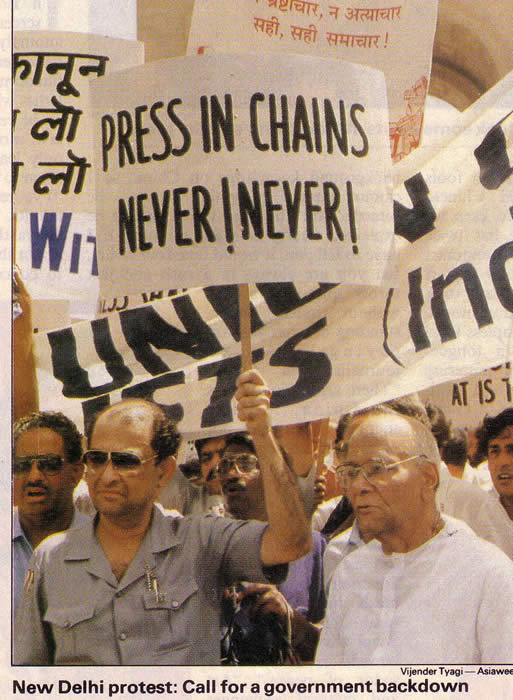

Anonymous: The Italian Connection. Asiaweek, Jan.15, 1988, pp. 12-18.

Anonymous: Now, Terror in the South. Asiaweek, Jan.22, 1988, pp. 12-14.

Mathews K. George and Valli Dharmarajah: The Bloody Trail to the South. South (London), Jan.1988, pp.66-67.

Pran Chopra: Colombos Policies Strike a Chord. South (London), Jan.1988, p. 74.

Sri Lanka correspondent: Bad day at Batticaloa. Economist, Jan.23, 1988, p.20 & 22.

Power-Sharing in Sri Lanka [Views of Gamini Dissanayake and Neelan Tiruchelvam]. Asiaweek, Jan. 29, 1988, p. 58.

That Rajiv Gandhi suffered from vanity, ignorance and pomposity (conveniently abbreviated as VIP) syndrome became exposed in how he handled the post-MGR political equations in the Tamil Nadu. And as a modus operandi to this politicking in the Tamil Nadu, he was promised a knock-out victory against the LTTE by the handlers of the Indian army. Rajiv’s then plight had been anticipated by the English poet Thomas Gray (1716-1771), in his Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College (1742). Here are those lines:

‘Yet ah! Why should they know their fate?

Since sorrow never comes too late,

And happiness too swiftly flies

Thought would destroy their paradise.

No more; where ignorance is bliss,

Tis folly to be wise.’

The first item in this part 5 authored by Saeed Naqvi (though Nov.1987 was its cover date) really appeared in December 1987 and provides a background-summary to the Rajiv – V.P. Singh split in 1987. The wheel of political fortune would turn towards Singh, who would eventually succeed Rajiv as the Indian prime minister in late 1989. As Naqvi concluded his commentary, by the end of 1987, “With the Left and the Right vying for [V.P.]Singh’s support and Gandhi’s grip on the middle ground rapidly weakening, India’s political future promises some interesting twists.” When 1988 dawned, what Rajiv and his Congress Party panderers yearned for was a quick victory for the Indian army against the LTTE in Eelam. But the Indian troops couldn’t grasp the battle plans of the LTTE.

Asiaweek Jan 15 1988 Sonia GandhiCompared to New Delhi-based Pran Chopra’s pom-pom swinging spin that “The Indian army is disarming Tamil militants faster than Sri Lankan troops could have managed…”, Colombo-based Mervyn de Silva (contributing under the by-line ‘Sri Lanka correspondent’) assessed the failure of the Rajiv-Jayewardene Accord within six months perceptively; “If the Indians want the agreement to work, they will have to offer the Tamils something more positive than mere suppression of the guerrillas. That means the resettlement of refugees, and provincial elections. But elections are hardly possible so long as the guerrillas can stroll in and do what they did in Batticaloa. India’s credibility is at risk.”

For obvious reasons, I also reproduce a cover story on Sonia Gandhi, which appeared in the Asiaweek of Jan. 15, 1988. Since Sonia Gandhi currently represents the real power in the debased and decadent Congress Party, it is not irrelevant to learn the then status and the hidden power Sonia Gandhi wielded in New Delhi 20 years ago.

Wherever they appear, words within parenthesis, in italics and in bold fonts are as in the originals.

The Many Faces of V.P. Singh

[Saeed Naqvi; South (London), Nov. 1987.]

Vishwanath Pratap Singh is a political player cast in many conflicting roles. The former minister is known both as a crusader against corruption and as a shrewd strategist seeking to oust Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. Some see him as a friend of the right-wing Hindu party, the Bharatiya Janata; others, including Singh himself, say he is an ally of the Left.

What is clear, however, is that Singh has raised the issues and unleashed the forces which may determine the outcome of the 1989 general election. Six months ago, when the government was buckling under the weight of allegations about illegal defence deals, it was even being suggested that the then President, Giani Zail Singh, was preparing to use his extraordinary powers to sack Gandhi and elevate V.P. Singh to the prime minstership. When Gandhi took over in December 1984, Singh was his favourite minister and confidante. Then a crackdown by Singh’s finance ministry on tax evasion, including foreign exchange fraud by leading industrialists, backfired on the special relationship between the two.

It was the start of a spectacular fall from power by Singh. He was shunted aside to the defence ministry in January, from where he resigned in April after launching an investigation into defence contracts. In July, Gandhi sacked him from the ruling Congress (I) party, though Singh had earlier offered to resign in anticipation of such a move.

The split between Singh and Gandhi can be traced to the era when the late Indira Gandhi was in power. Her most senior colleague, finance minister Pranab Mukherjee, proved a strong patron of Dhirubhai Ambani, a textile merchant who turned his small company into the country’s third largest in the space of 10 years. In the process, he ended the 100-year domination of textiles by Bombay Dyeing, controlled by Nusli Wadia. Mukherjee was tipped to take over after Mrs Gandhi’s assassination. But when the ruling party opted for Rajiv Gandhi instead, Mukherjee was eased out, and Ambani lost a key political ally.

Wadia, a descendant of Mohammed Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s founder, fitted in better with the educated elite surrounding India’s new Prime Minister. And when Singh took over the finance portfolio and began his campaign against tax evasion, Wadia called on the finance ministry to hire a US-based agency, Fairfax, to investigate Ambani. Having pulled strings with the Prime Minister, Singh and the finance ministry, all Wadia needed was a press campaign to bring Ambani to heel.

Ramnath Goenka, owner of the Indian Express chain, knew Wadia and Ambani equally well. Because of his own rags-to-riches career, Goenka had much more in common with Ambani, who suffered a massive stroke early in 1986. But Goenka’s political sympathies have always been with the Bharatiya Janata Party. Vije Raje Scindia, an influential BJP leader, and her son Madhorao Scindia, the minister of railways, held majority shares in Bombay Dyeing. They are said to have pressured Goenka into publishing a series of articles in March 1986 on Ambani’s allegedly irregular dealing abroad.

Asiaweek Jan 22 1988Then, in December 1986, a letter from the Fairfax agency, now generally believed to be a forgery, fell into government hands. It indicated that Fairfax was investigating the foreign exchange dealings of Ajitabh Bachchan, brother of India’s most popular film star, Amitabh Bachchan. Both were among Rajiv Gandhi’s closest friends. At about the same time, two unidentified sleuths turned up in Switzerland to question Ajitabh about his purchase of property in Geneva. A panic-stricken Ahitabh turned to Gandhi, who became alarmed at the way foreign agencies were investigating his friends on behalf of Singh’s finance ministry.

There was a raid on Goenka’s premises to search for more so-called Fairfax documents. In one stroke, the enemies of Ambani had also become the enemies of the Prime Minister. Ambani’s role in all this is unclear. But Singh was shifted to the defence ministry on the grounds that there was tension on the Pakistan border. Even at the defence ministry, though, Singh maintained his offensive against corruption. He continued to call Gandhi his leader, while winning more plaudits from the opposition.

Singh ordered an inquiry into alleged kickbacks in a submarine deal signed with West Germany when Indira Gandhi was in power – a move which brought him under heavy fire from ruling party members. He was accused of politicking, and in April he resigned both his portfolio and his seat in parliament. Within days India was shaken by a new story about a US$ 1.4 billion contract Rajiv Gandhi’s government had negotiated with Bofors of Sweden for 400 field guns. Swedish radio reported that millions of dollars had been paid to Indian middlemen in kickbacks.

Then Goenka and his young editor, Arun Shourie, another BJP sympathiser, turned the guns of the Indian Express on the Prime Minister. All the opposition backed Singh’s crusade against corruption, and for an entire session of parliament the government was under fire. The opposition and the Indian Express have been highly effective, with Gandhi’s leadership taking a battering. The irony is that nothing has been proved.

There is a parallel with 1974, when the Indian Express and the precursor of the BJP, the Jana Sangh, orchestrated a campaign for clean government against Indira Gandhi. At the fore was the Bihar movement, launched under the leadership of the late Jaya Prakash Narayan, a follower of Mahatma Gandhi. Pressure from this movement was largely responsible for the introduction of a state of emergency in 1975 – which prepared the ground for Mrs Gandhi’s defeat in 1977. On this occasion, the Indian Express, like-minded newspapers and the BJP are casting Singh in the role of Narayan, who also renounced power. However, important political changes have taken place in India since the 1970s. And these present obstacles to the creation of a united opposition front capable of taking on the ruling party. For example, the Left is more of a force than it was in the mid-1970s. The Communist Party Marxist and the Communist Party of India are not only united, but also effectively in power in West Bengal, Kerala and Tripura.