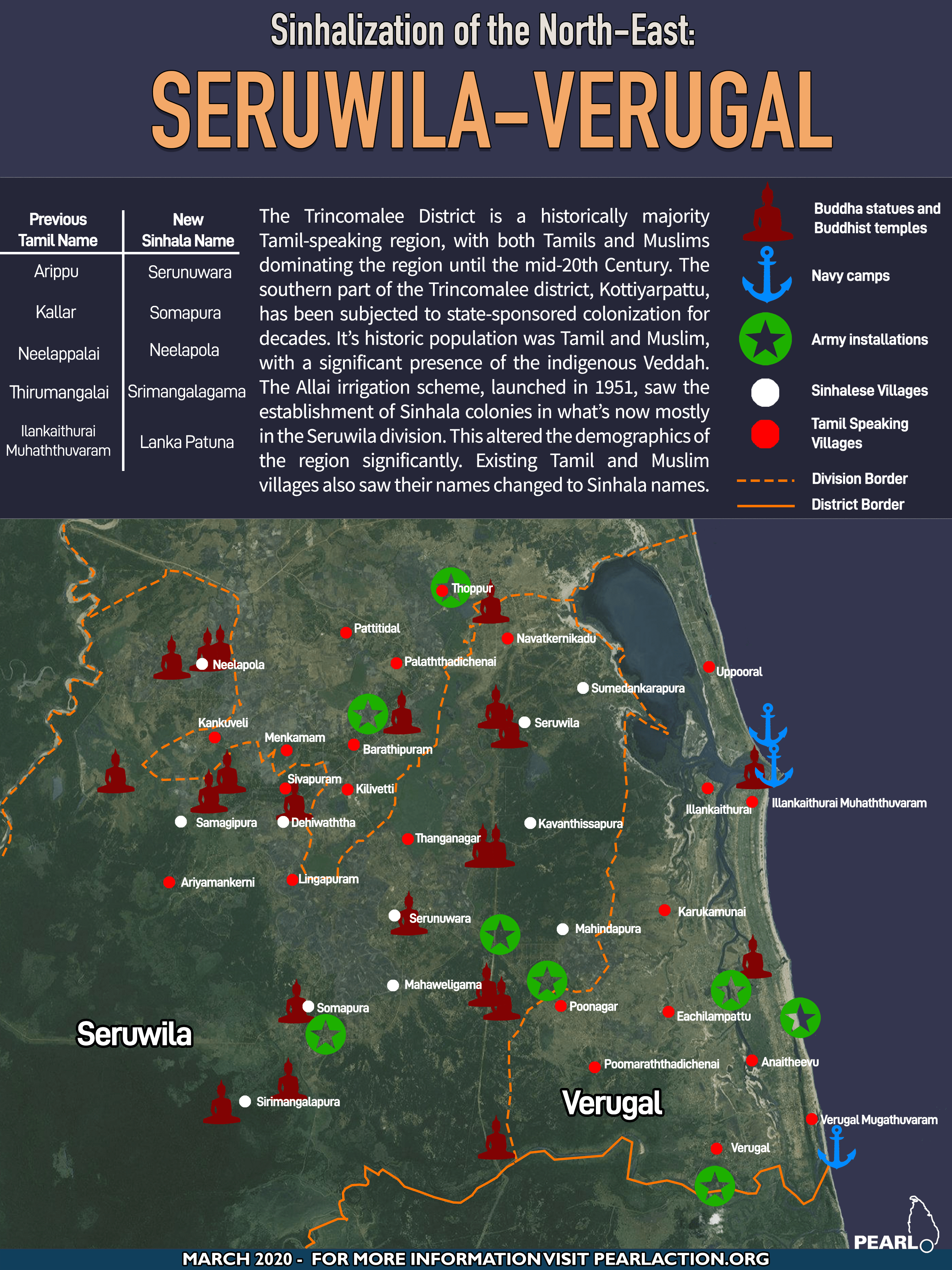

Sinhalization of the North-East -Seruwila-Verugal

The Trincomalee District has been subject to the government’s colonization efforts dating back to independence from British rule in 1948. The district’s geography gives it added significance, as the link to the northern part of the traditional Tamil homeland, and its natural and strategic resources, including its natural deep-sea harbour.1 Trincomalee was a historically majority Tamil-speaking region, with both Tamils and Muslims dominating the district until the mid-20th Century. But land settlement and development policies of successive governments have been “a major factor in altering the demography of the eastern province in favor of the Sinhalese”.2

The establishment of irrigation and development schemes is thought to be a pretext to state-sponsored colonization and a deliberate re-engineering of the demographics of the region. The settlement of Sinhalese in Trincomalee is seen as a strategic way to “weaken the ethnic balance of minorities and sabotage their territorial-based autonomy claims”.3 Trincomalee’s location between key war-time battlegrounds in the Vanni and Batticaloa made it a key supply route for the LTTE. This made it even more important for the government to take control in this area and “block these routes through a combined strategy of settling Sinhalese in buffer zones and subsequently militarising these zones”.4

The southern part of the Trincomalee district, Kottiyarpattu, which lies north of the border to the Batticaloa district and south of Koddiyar Bay has also been subjected to state-sponsored colonization. It’s historic population was Tamil and Muslim, with a significant presence of the indigenous Veddah population. The Coastal Veddah of the Eastern Provinces reside along coastal regions of Batticaloa and Trincomalee and now speak the Tamil language.5 Irrigation schemes have resulted in the forced displacement of these communities to government reservations, resulting in a population decline.6

Presently, the Kottiyarpattu area is divided into three divisional secretariats (DS), the Muttur DS, Seruwila DS and Verugal DS. This report will focus on the latter two, which were both administered together as the Seruwila DS until 1988 when the Tamil area was separated as the Verugal DS. This created a majority Sinhala Seruwila DS and a majority Tamil Verugal DS.

Department of Census and Statistics, (2012), Population by Ethnicity and DS Division Trincomalee District, 2012, Retrieved from Statistics website.

SINHALA SETTLEMENTS

The Allai irrigation scheme was launched by then-president D.S.Senanayake in the south of the Trincomalee District in 1951. The scheme eventually altered the demographics of the region significantly7,8. The scheme saw the construction of an anicut through the Verugal river, providing irrigation to the region, which at the time fell under the Kottiyar Assistant Government Agent’s Division (AGA). Colonies, most of them Sinhalese, were then established in the area, falling now largely in the Seruwila division.

Virtually all Sinhalese in this region are relatively recent arrivals and their descendants, with most of them originally from Kurunegala, Hambantota and elsewhere on the south coast.9 Although two colonies, Sivapuram and Lingapuram, were settled with Tamils, these were people settled from within Kottiyarpattu, including from Muttur, the neighboring DS.

Tissa Devendra’s contribution to the Island titled “Settling Pioneers in Allai in 1953” narrates the colonial project coordinated by the government of Sri Lanka. In his historical recollection of his voyage as a young Land Officer in 1953, he writes10:

“Massive irrigation reservoirs had been restored and the cultivable land distributed to “colonists” hopefully expected to develop into a “sturdy, land-owning peasantry”. These ‘colonies’ were in uninhabited or thinly populated regions and the few local farmers Were the first settlers. Most colonists, however, came from the densely populated villages of the south-west region and the central hills. Colonists were settled in government-built houses round brand-new village centres of co-operative stores, schools, dispensaries, post-offices, bazaars and other utilities. Resident Colonization Officers represented the administration, serving all the colonists’ needs, as the Headmen of the old villages had little jurisdiction over them.”

In addition to the formation of new settlements, there was also Sinhalization of existing Tamil and Muslim villages, resulting in many traditional villages to be officially renamed in Sinhala. Violence and massacres by Sinhala colonists against Tamil villagers were rare before the 1980s, however, this escalated as anti-Tamil pogroms occurred across the country. The most serious violence occurred in May-June 1985, when “every Tamil village in walking distance to Sinhala colonies” was burnt to the ground.11 Earlier that year the Sinhala settlers were given weapons and training while the army increased and solidified their presence in the area. 12

“The villages of Kilivetti, Menkamam, Sivapuram, Kankuveli, Pattitidal, Palaththadichenai, Arippu, Poonagar, Mallikaithivu, Peruveli, Munnampodivattai, Manalchenai, Bharatipuram, Lingapuram, Eechchilampattai, Karukkamunai, Mavadichchenai, Muttuchenai and Valaithottam were razed to the ground by a looting and plundering mob of Sinhala soldiers, policemen, home guards, and ordinary civilians. Over 80 people were reportedly killed, and 200 disappeared.”13

Tamil retaliation became regular, with periodic attacks against settlers, designed to force their return to the South. From the late 80s, the LTTE controlled much of the Tamil parts of this area, administering the population while maintaining a line of control against the Sri Lankan military. During the ceasefire in the early 2000s, violence erupted between Tamils and Muslims in the area. In 2006 the LTTE retreated as the Sri Lankan military advanced, with most of the population of Kottiyarpattu displaced by the fighting.

Seruwila Division

The Seruwila Divisional Secretariat is a division today inhabited largely by Sinhala settlers and their descendents. Historically this region was home to Tamil and Muslim villages. It now encompasses 16 Grama Niladhari Divisions (GNs), the majority of which are Sinhala dominated. The total population of the DS according to the 2012 census is 13,546, out of which 9,293 are Sinhalese, 1,819 Tamil and 2,426 Muslim.

The Tamil-speaking people are largely in the areas of Ariyamankerni, Lingapuram, Navatkernikaadu, Sivapuram and Thanganagar.14 However many previously Tamil villages were officially given Sinhala names, as the Sinhala settler population increased.

For example, Neelappalai was a Tamil village, which was also scheduled for development as a colony under the Allai Scheme. However in 1958, “rough elements” from Polonnaruwa were settled overnight.15 The village had a mixed population, with Tamils slowly being driven out, until the island-wide 1983 anti-Tamil pogroms, when the remaining Tamil villagers were chased out. The village is now completely Sinhala and known as Neelapola.

Verugal Division

The Verugal division is virtually all Tamil-speaking, with Tamils and Veddah making up the entire population. Wedged between the Indian Ocean and the Seruwila division, with the Verugal river forming its southern border, it includes 10 GN divisions. It was virtually under complete LTTE control until 2006 and saw heavy fighting as the LTTE pulled out. This region is renowned for its rich cultural history, including its Hindu temples and Veddah traditions.

The newly built Buddhist temple on top of the cliff in Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram

The original Neeliyamman temple, photographed over 30 years ago

BUDDHISIZATION

Some of the new Sinhala villages were formed around archaeological sites, which have been developed into Buddhist temples in recent times. The Seruwila Mangala Viharaya was opened in 2009, after initially being built-in 1930. A Sinhala monk had “re-discovered” the ruins in 1922.16 At the time, the area was inhabited by Tamils, Muslims and the Veddah population.17 Sinhalese mythology claims an ancient temple, built in Seruwila over 2000 years ago, was abandoned after “the pressure of Tamil invasions from the north”. The stupa and its surroundings, including several monuments, cover approximately 85 acres and it was declared as an Archaeological Reserve in 1962.18

Like in Seruwila, each of the Sinhala settlements had a Buddhist temple built within it, with the resident monks the most important leaders in the community. They often encouraged Sinhala claims to the land on an ethno-religious basis. The resident monk at the Neelapola temple, for example, stayed in the area throughout the war and encouraged his followers not to abandon their role as “frontiersmen”.19

While many of the Buddhist temples in the Seruwila division were built as the Sinhala population increased, in Verugal, without a Sinhala population, the military and Buddhist monks from the south grabbed land to build their temples.

The village of Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram lies on the coast, where the Ullakkale Lagoon opens into the Indian Ocean. A rocky outcrop on a hill overlooking the inlet was the site of the ancient Kunjumappa Periyasamy Temple, worshipped by Tamil-speaking Veddah and Tamils since ancient times.

According to Sinhala folklore, the area is sacred as it was the spot where Indian royalty arrived with the tooth of the Buddha in the 4th Century AD.20 With the beginning of the ceasefire in 2002, a group of Sinhala Buddhists came to the area and planned for a Buddhist shrine, as Tamil villagers watched in concern. Supposedly the arrogance of the visitors offended the villagers, who smashed the statues they had left behind.

When the local population was displaced by fighting in 2006, the Sri Lankan military took over the area from the LTTE. Former Chief Justice Sarath Silva, who was also a member of a group responsible for the development of the Buddhist complex in Seruwila, was taken on a tour by the military after they captured the area, when he ‘discovered’ the ‘Lanka Patuna Samudragiri Vihara’. The Archaeology Department designated the area as a historic Buddhist site. When the villagers returned in 2008, they found several Hindu temples destroyed, including the Veddah’s traditional place of worship on the hill. A large Buddha statue, and a new temple, constructed by the army, was found in its place. The Buddhist temple was formally opened on March 26th, 2007 by Major General Parakirama Pannipitiyawal, leader of Sri Lanka’s Eastern Security Force. The village was also officially renamed to the Sinhala “Lanka Patuna”.21 A new bridge was built, crossing the inlet, making access easy for hundreds of Sinhala devotees, who come to worship at the temple every day.

Tamil villagers say the name change of the village to Lanka Patuna has also been made in new birth certificates, causing more anger in the community. The neighbouring Tamil village of Vaalaithottam, which means banana garden, has also been identified as the Sinhala for banana garden ‘Kisalkedowatha’, in official documentation, with a phonetic English translation of the Sinhala name.

To this day, there is a heavy navy presence in the village. Locals told PEARL researchers in February 2020 that they must disclose any visitors from outside the village to navy officials. Due to the fear of retaliation, there was reluctance by villagers to openly talk to our researchers. The securitization of the area has resulted in a climate of fear for the population.

The Buddha statue constructed on top of the Ilankai Muhaththuvaram cliff

The Archaeological Department’s sign is often the dreaded first indication that the government is about to take over the land.

Around 7km south of Ilankaiththurai lies the village of Kallady. The Sri Malai Neeliyamman temple, belonging to Tamil people, was located on a rocky hill on the side of a road. This temple was demolished and replaced by a Buddhist temple after the area was taken over by the military.

Prior to 2006, a communications tower was established for telecasting the LTTE’s Voice of the Tigers radio station, within temple premises. As the fighting escalated, the Sri Lankan Air Force destroyed the temple through airstrikes. Following the designation of the area as a historic Buddhist site by the Archaeology Department, Pashana Pabbatha Rajamaha Vihara, a Buddhist temple was established.

In July 2007, the displaced Tamils returning to their village were prohibited from entering or reconstructing their place of worship, both by the army and Buddhist monks, according to members of the temple committee.22

In 2008, the University Teachers for Human Rights (Jaffna) [UTHRJ] stated:

“The people are unable to protest for fear of the consequences. The Government’s intentions in this connection are clearly seen under its plan for Eastern Revival, under the Ministry for Nation Building. Its plan under Cultural Heritage lists several conservation projects.” 23

The Tamil people have subsequently moved their place of worship to the road, on the periphery of the new Buddhist compound. Two Sri Lankan police officials have been assigned to the location on a 24/7 basis, for the ‘protection’ of the site. Dozens of Sinhala Buddhists come to the site every day according to members of the temple committee. Tamils are prevented from entering the compound. When PEARL researchers visited the compound in 2020, the police officials questioned where we came from, asked for national IDs and allowed entry only following approval from the Buddhist monk at the site.

The monk, Ratnapura Devananda Thero, is notorious for his hardline views and frequent threats to the Tamil population. He has shared with Sinhala media that he has been given security by police officials and food was being provided by the navy. He has been described as “a tough character fighting a lone battle with the Tamil political parties in the east…without a single Buddhist in the area”.24 For several years now, a radio interview in Sinhala with the former medical doctor turned monk, is blared through loudspeakers throughout the day, audible from a distance. In the interview, he speaks of the ‘proud defeat of terrorism’ and claims the site to be a Buddhist heritage site.

On September 26th, 2016 the new Neeliyamman temple was burnt to the ground, allegedly by Buddhist temple officials. A Sinhalese individual was subsequently detained following this incident and was released on bail. In January 2019 the court case was dropped.

Buddhist monk Ratnapura Devananda, who took over the site of the Neeliyamman temple in Kallady.

The new Kallady Buddhist temple perimeter wall, with the Tamil temple in the background

MILITARIZATION

There are at least seven military installations in the Seruwila-Verugal area, with at least three navy camps and four army installations. The Civil Security Department also has at least one camp. There do not appear to be any military camps in the Sinhala settlements, apart from the Seruwila Civil Security Department camp in Somapura. As of February 2020, there were several military checkpoints along the A15 road, the main thoroughfare that bifurcates this region.

Seven acres of land belonging to Tamils have been taken and turned into a naval camp near Verugal Muhaththuvaram. Although the landowners have the necessary documentation, their land has not been returned. The landowners told PEARL researchers that they have been prevented by the navy from even retrieving coconuts from the trees on their land. They also said that since the new government took power in November, navy officials have prevented the landowners from entering their land.

Two acres of land belonging to Tamils in Anaitivu, Vallaithottam have been used to establish an army camp and the people have been denied access.

A large navy camp, called SLNS Lankapatuna, is located just north of the new Buddhist temple at Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram.

A satellite camp is also located closer to the bridge leading to the temple.

The headquarters of the Sri Lanka National Guard’s 24 Battalion is located in Eachchilampattu.

The region covering what is now called Seruwila and Verugal has seen much change since Sri Lanka’s Independence. While the initial settlements of Sinhala colonizers in the 1950s faced some resistance from Tamil politicians, who argued it went against the Land Settlement Ordinance as preference was given to settlers from outside the province, incidents of confrontation and violence was rare until the 1980s. Once anti-Tamil pogroms erupted on a larger scale, Tamils in some areas were subjected to ethnic cleansing. In some villages the demographics shifted permanently, turning previously Tamil-speaking villages into entirely Sinhala ones. From the forced expulsion and massacres by the Sri Lankan armed forces against Tamils in the 1980s to the current occupation of religious sites, particularly in Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram and Kallady, the Sri Lankan state is continuing its project of Sinhalising the Trincomalee district in this area.25 The local population, which includes a Tamil-speaking Veddah minority, often themselves neglected by the Tamil community, feels the pressure of Sinhalization and continues to resist it. While the Seruwila Division has effectively been Sinhalised, in the Verugal Division, fear of Sinhalization and anger at the military occupation of land and the Buddhist occupation of traditionally Tamil places of worship is increasing.

Tamil Version of Infographic available here

Footnotes

1 Refugee Review Tribunal. (2005). Rrt Research Response.

2 Yusoff, Mohammad Agus & Sarjoon, Athambawa & Awang, Azmi & Hamdi, Izham. (2015). Land Policies, Land-based Development Programs and the Question of Minority Rights in Eastern Sri Lanka. Journal of Sustainable Development. 8. 10.5539/jsd.v8n8p223.

3Yusoff, M.A. & Sarjoon, A. & Awang, A. & Hamdi, I. (2015). Land Policies, Land-based Development Programs and the Question of Minority Rights in Eastern Sri Lanka. Journal of Sustainable Development. 8. 10.5539/jsd.v8n8p223.

4Gaasbeek, T. (2010). Bridging troubled waters? : everyday inter-ethnic interaction in a content of violent conflict in Kottiyar Patty, Trincomalee, Sri Lanka.

5Bartholomeusz, D., Farisz, H., & Kotagama, S. (2012). Indigenous communities in Sri Lanka: the Veddahs. Peliyagoda, Sri Lanka: Ceylon Tea Service.

6 Childs, K. (2017, July 5). The Last Veddas of Sri Lanka. Retrieved from https://newint.org/features/web-exclusive/2017/01/10/the-last-veddas-of-sri-lanka

7 UTHRJ. (n.d.). Colonization & Demographic Changes in the Trincomalee District and Its Effects on the Tamil Speaking People. Retrieved from http://www.uthr.org/Reports/Report11/appendix2.htm

8LTTE Peace Secretariat. (2005). Demographic changes in the Tamil Homeland in the Island of Sri Lanka Over the Last Century.

9 Gaasbeek, T. (2010). Bridging troubled waters? : everyday inter-ethnic interaction in a content of violent conflict in Kottiyar Patty, Trincomalee, Sri Lanka.

10Devendra, T. (2006, August 6). Stuck in the Mud: Settling pioneers in Allai in 1953. Sunday Island. Retrieved from http://www.island.lk/2006/08/06/features4.html

11 Gaasbeek, T. (2010). Bridging troubled waters? : everyday inter-ethnic interaction in a content of violent conflict in Kottiyar Patty, Trincomalee, Sri Lanka.

12Hoole, R., 2001. Myth, decadence and murder: Sri Lanka – the arrogance of power.

13 Gaasbeek, T. (2010). Bridging troubled waters? : everyday inter-ethnic interaction in a content of violent conflict in Kottiyar Patty, Trincomalee, Sri Lanka.

14Admin, S. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved from http://seruwila.ds.gov.lk/index.php/en/common-details/population.html#population-by-ethnic

15 UTHRJ. (1996, March 5). Trincomalee District in February 1996: Focusing on the Killiveddy Massacre. Retrieved from http://www.uthr.org/bulletins/bul10.htm

16Gaasbeek, T. (2010). Bridging troubled waters? : everyday inter-ethnic interaction in a content of violent conflict in Kottiyar Patty, Trincomalee, Sri Lanka.

17 Jayasekera, K. D. (2003, September 8). The saga of Seruwila Mangala Viharaya. The Saga of Seruwila Mangala Viharaya. Retrieved from http://lankabhumi.org/seruwila.htm

18Centre, UNESCO. W.H. (n.d.). Seruwila Mangala Raja Maha Vihara. Retrieved from https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5083/

19 Gaasbeek, T. (2010). Bridging troubled waters? : everyday inter-ethnic interaction in a content of violent conflict in Kottiyar Patty, Trincomalee, Sri Lanka.

20 Tamil Guardian. (2016, August 16). From Ilankaiththurai to Lanka Patuna. Retrieved from https://www.tamilguardian.com/content/ilankaiththurai-lanka-patuna-0

22 PEARL Interviews 2020

24 Amazing Lanka. (2016, December 28). Pashana Pabbatha Rajamaha Viharaya. Retrieved from https://amazinglanka.com/wp/pashana-pabbatha-rajamaha-viharaya/

25LTTE Peace Secretariat (April 2008). Demographic changes in the Tamil homeland in the island of Sri Lanka over the last century.

Sinhalization of the North-East: Verugal

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.