Sinhalization of the North-East:

Seruwila-Verugal

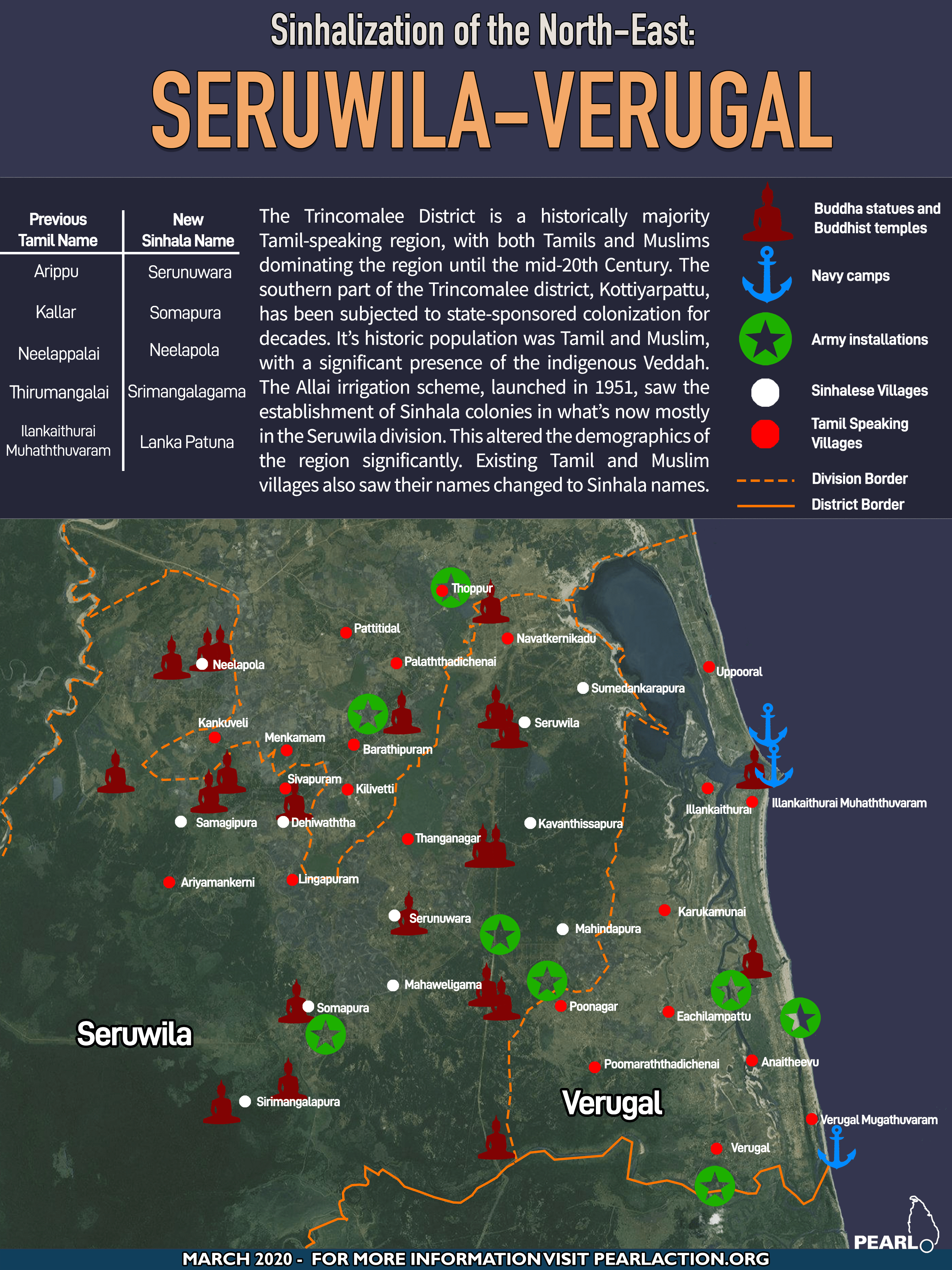

The Trincomalee District has been subject to the government’s colonization efforts dating back to independence from British rule in 1948. The district’s geography gives it added significance, as the link to the northern part of the traditional Tamil homeland, and its natural and strategic resources, including its natural deep-sea harbour.1 Trincomalee was a historically majority Tamil-speaking region, with both Tamils and Muslims dominating the district until the mid-20th Century. But land settlement and development policies of successive governments have been “a major factor in altering the demography of the eastern province in favour of the Sinhalese”.2 The establishment of irrigation and development schemes is thought to be a pretext to state-sponsored colonization and a deliberate re-engineering of the demographics of the region. The settlement of Sinhalese in Trincomalee is seen as a strategic way to “weaken the ethnic balance of minorities and sabotage their territorial-based autonomy claims”.3 Trincomalee’s location between key war-time battlegrounds in the Vanni and Batticaloa made it a key supply route for the LTTE. This made it even more important for the government to take control in this area and “block these routes through a combined strategy of settling Sinhalese in buffer zones and subsequently militarising these zones”.4

The southern part of the Trincomalee district, Kottiyarpattu, which lies north of the border to the Batticaloa district and south of Koddiyar Bay has also been subjected to state-sponsored colonization. It’s historic population was Tamil and Muslim, with a significant presence of the indigenous Veddah population. The Coastal Veddah of the Eastern Provinces reside along coastal regions of Batticaloa and Trincomalee and now speak the Tamil language.5 Irrigation schemes have resulted in the forced displacement of these communities to government reservations, resulting in a population decline.6

Presently, the Kottiyarpattu area is divided into three divisional secretariats (DS), the Muttur DS, Seruwila DS and Verugal DS. This report will focus on the latter two, which were both administered together as the Seruwila DS until 1988 when the Tamil area was separated as the Verugal DS. This created a majority Sinhala Seruwila DS and a majority Tamil Verugal DS.

Department of Census and Statistics, (2012), Population by Ethnicity and DS Division Trincomalee District, 2012, Retrieved from Statistics website

.

SINHALA SETTLEMENTS

The Allai irrigation scheme was launched by then-president D.S.Senanayake in the south of the Trincomalee District in 1951. The scheme eventually altered the demographics of the region significantly7,8. The scheme saw the construction of an anicut through the Verugal river, providing irrigation to the region, which at the time fell under the Kottiyar Assistant Government Agent’s Division (AGA). Colonies, most of them Sinhalese, were then established in the area, falling now largely in the Seruwila division. Virtually all Sinhalese in this region are relatively recent arrivals and their descendants, with most of them originally from Kurunegala, Hambantota and elsewhere on the south coast.9 Although two colonies, Sivapuram and Lingapuram, were settled with Tamils, these were people settled from within Kottiyarpattu, including from Muttur, the neighbouring DS.

Tissa Devendra’s contribution to the Island titled “Settling Pioneers in Allai in 1953” narrates the colonial project coordinated by the government of Sri Lanka. In his historical recollection of his voyage as a young Land Officer in 1953, he writes10:

“Massive irrigation reservoirs had been restored and the cultivable land distributed to “colonists” hopefully expected to develop into a “sturdy, land-owning peasantry”. These ‘colonies’ were in uninhabited or thinly populated regions and the few local farmers Were the first settlers. Most colonists, however, came from the densely populated villages of the south-west region and the central hills. Colonists were settled in government built houses round brand-new village centres of co-operative stores, schools, dispensaries, post-offices, bazaars and other utilities. Resident Colonization Officers represented the administration, serving all the colonists’ needs, as the Headmen of the old villages had little jurisdiction over them.”

In addition to the formation of new settlements, there was also Sinhalization of existing Tamil and Muslim villages, resulting in many traditional villages to be officially renamed in Sinhala. Violence and massacres by Sinhala colonists against Tamil villagers were rare before the 1980s, however, this escalated as anti-Tamil pogroms occurred across the country. The most serious violence occurred in May-June 1985, when “every Tamil village in walking distance to Sinhala colonies” was burnt to the ground.11 Earlier that year the Sinhala settlers were given weapons and training while the army increased and solidified their presence in the area. 12

“The villages of Kilivetti, Menkamam, Sivapuram, Kankuveli, Pattitidal, Palaththadichenai, Arippu, Poonagar, Mallikaithivu, Peruveli, Munnampodivattai, Manalchenai, Bharatipuram, Lingapuram, Eechchilampattai, Karukkamunai, Mavadichchenai, Muttuchenai and Valaithottam were razed to the ground by a looting and plundering mob of Sinhala soldiers, policemen, home guards, and ordinary civilians. Over 80 people were reportedly killed, and 200 disappeared.”13

Tamil retaliation became regular, with periodic attacks against settlers, designed to force their return to the South. From the late 80s the LTTE controlled much of the Tamil parts of this area, administering the population, while maintaining a line of control against the Sri Lankan military. During the ceasefire in the early 2000s, violence erupted between Tamils and Muslims in the area. In 2006 the LTTE retreated as the Sri Lankan military advanced, with most of the population of Kottiyarpattu displaced by the fighting.

Seruwila Division

The Seruwila Divisional Secretariat is a division today inhabited largely by Sinhala settlers and their descendents. Historically this region was home to Tamil and Muslim villages. It now encompasses 16 Grama Niladhari Divisions (GNs), the majority of which are Sinhala dominated. The total population of the DS according to the 2012 census is 13,546, out of which 9,293 are Sinhalese, 1,819 Tamil and 2,426 Muslim. The Tamil-speaking people are largely in the areas of Ariyamankerni, Lingapuram, Navatkernikaadu, Sivapuram and Thanganagar.14 However many previously Tamil villages were officially given Sinhala names, as the Sinhala settler population increased.

For example, Neelappalai was a Tamil village, which was also scheduled for development as a colony under the Allai Scheme. However in 1958, “rough elements” from Polonnaruwa were settled overnight.15 The village had a mixed population, with Tamils slowly being driven out, until the island-wide 1983 anti-Tamil pogroms, when the remaining Tamil villagers were chased out. The village is now completely Sinhala and known as Neelapola.

Verugal Division

The Verugal division is virtually all Tamil-speaking, with Tamils and Veddah making up the entire population. Wedged between the Indian Ocean and the Seruwila division, with the Verugal river forming its southern border, it includes 10 GN divisions. It was virtually under complete LTTE control until 2006 and saw heavy fighting as the LTTE pulled out. This region is renowned for its rich cultural history, including its Hindu temples and Veddah traditions.

The newly built Buddhist temple on top of the cliff in Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram

The original Neeliyamman temple, photographed over 30 years ago

The current Neeliyamman temple, moved outside its original premises

The newly built Buddhist temple on top of the cliff in Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram

The newly built Buddhist temple on top of the cliff in Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram

Sign in Sinhala only and Buddhist flag in the Tamil village of Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram

The capture of Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram by the Sri Lankan Army in 2006. The Tamil temple can be seen behind the troops.

Kallady Buddhist temple, on the site of the Neeliyamman temple

The newly built Buddhist temple on top of the cliff in Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram

The original Neeliyamman temple, photographed over 30 years ago

The current Neeliyamman temple, moved outside its original premises

The newly built Buddhist temple on top of the cliff in Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram

The newly built Buddhist temple on top of the cliff in Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram

Sign in Sinhala only and Buddhist flag in the Tamil village of Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram

The capture of Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram by the Sri Lankan Army in 2006. The Tamil temple can be seen behind the troops.

Kallady Buddhist temple, on the site of the Neeliyamman temple

The newly built Buddhist temple on top of the cliff in Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

BUDDHISIZATION

Some of the new Sinhala villages were formed around archaeological sites, which have been developed into Buddhist temples in recent times. The Seruwila Mangala Viharaya was opened in 2009, after initially being built-in 1930. A Sinhala monk had “re-discovered” the ruins in 1922.16 At the time, the area was inhabited by Tamils, Muslims and the Veddah population.17 Sinhalese mythology claims an ancient temple, built in Seruwila over 2000 years ago, was abandoned after “the pressure of Tamil invasions from the north”. The stupa and its surroundings, including several monuments, cover approximately 85 acres and it was declared as an Archaeological Reserve in 1962.18

Like in Seruwila, each of the Sinhala settlements had a Buddhist temple built within it, with the resident monks the most important leaders in the community. They often encouraged Sinhala claims to the land on an ethno-religious basis. The resident monk at the Neelapola temple for example, stayed in the area throughout the war and encouraged his followers not to abandon their role as “frontiersmen”.19

While many of the Buddhist temples in the Seruwila division were built as the Sinhala population increased, in Verugal, without a Sinhala population, the military and Buddhist monks from the south grabbed land to build their temples.

The village of Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram lies on the coast, where the Ullakkale Lagoon opens into the Indian Ocean. A rocky outcrop on a hill overlooking the inlet was the site of the ancient Kunjumappa Periyasamy Temple, worshipped by Tamil-speaking Veddah and Tamils since ancient times.

According to Sinhala folklore, the area is sacred as it was the spot where Indian royalty arrived with the tooth of the Buddha in the 4th Century AD.20 With the beginning of the ceasefire in 2002, a group of Sinhala Buddhists came to the area and planned for a Buddhist shrine, as Tamil villagers watched in concern. Supposedly the arrogance of the visitors offended the villagers, who smashed the statues they had left behind.

When the local population was displaced by fighting in 2006, the Sri Lankan military took over the area from the LTTE. Former Chief Justice Sarath Silva, who was also a member of a group responsible for the development of the Buddhist complex in Seruwila, was taken on a tour by the military after they captured the area, when he ‘discovered’ the ‘Lanka Patuna Samudragiri Vihara’. The Archaeology Department designated the area as a historic Buddhist site. When the villagers returned in 2008, they found several Hindu temples destroyed, including the Veddah’s traditional place of worship on the hill. A large Buddha statue, and a new temple, constructed by the army, was found in its place. The Buddhist temple was formally opened on March 26th, 2007 by Major General Parakirama Pannipitiyawal, leader of Sri Lanka’s Eastern Security Force. The village was also officially renamed to the Sinhala “Lanka Patuna”.21 A new bridge was built, crossing the inlet, making access easy for hundreds of Sinhala devotees, who come to worship at the temple every day.

Tamil villagers say the name change of the village to Lanka Patuna has also been made in new birth certificates, causing more anger in the community. The neighbouring Tamil village of Vaalaithottam, which means banana garden, has also been identified as the Sinhala for banana garden ‘Kisalkedowatha’, in official documentation, with a phonetic English translation of the Sinhala name.

To this day, there is a heavy navy presence in the village. Locals told PEARL researchers in February 2020 that they must disclose any visitors from outside the village to navy officials. Due to the fear of retaliation, there was reluctance by villagers to openly talk to our researchers. The securitization of the area has resulted in a climate of fear for the population.

The Buddha statue constructed on top of the Ilankai Muhaththuvaram cliff

The Archaeological Department’s sign is often the dreaded first indication that the government is about to take over land.

Around 7km south of Ilankaiththurai lies the village of Kallady. The Sri Malai Neeliyamman temple, belonging to Tamil people, was located on a rocky hill on the side of a road. This temple was demolished and replaced by a Buddhist temple, after the area was taken over by the military.

Prior to 2006 a communications tower was established for telecasting the LTTE’s Voice of the Tigers radio station, within temple premises. As the fighting escalated, the Sri Lankan Air Force destroyed the temple through air strikes. Following the designation of the area as a historic Buddhist site by the Archaeology Department, Pashana Pabbatha Rajamaha Vihara, a Buddhist temple was established.

In July 2007, the displaced Tamils returning to their village were prohibited from entering or reconstructing their place of worship, both by the army and Buddhist monks, according to members of the temple committee.22

In 2008, the University Teachers for Human Rights (Jaffna) [UTHRJ] stated:

“The people are unable to protest for fear of the consequences. The Government’s intentions in this connection are clearly seen under its plan for Eastern Revival, under the Ministry for Nation Building. Its plan under Cultural Heritage lists several conservation projects.” 23

The Tamil people have subsequently moved their place of worship to the road, on the periphery of the new Buddhist compound. Two Sri Lankan police officials have been assigned to the location on a 24/7 basis, for the ‘protection’ of the site. Dozens of Sinhala Buddhist come to the site every day according to members of the temple committee. Tamils are prevented from entering the compound. When PEARL researchers visited the compound in 2020, the police officials questioned where we came from, asked for national IDs and allowed entry only following approval from the Buddhist monk at the site.

The monk, Ratnapura Devananda Thero, is notorious for his hardline views and frequent threats to the Tamil population. He has shared to Sinhala media that he has been given security by police officials and food was being provided by the navy. He has been described as “a tough character fighting a lone battle with the Tamil political parties in the east…without a single Buddhist in the area”.24 For several years now, a radio interview in Sinhala with the former medical doctor turned monk, is blared through loudspeakers throughout the day, audible from a distance. In the interview he speaks of the ‘proud defeat of terrorism’ and claims the site to be a Buddhist heritage site.

On September 26th, 2016 the new Neeliyamman temple was burnt to the ground, allegedly by Buddhist temple officials. A Sinhalese individual was subsequently detained following this incident and was released on bail. In January 2019 the court case was dropped.

Buddhist monk Ratnapura Devananda, who took over the site of the Neeliyamman temple in Kallady.

The new Kallady Buddhist temple perimeter wall, with the Tamil temple in the background

MILITARIZATION

There are at least seven military installations in the Seruwila-Verugal area, with at least three navy camps and four army installations. The Civil Security Department also has at least one camp. There do not appear to be any military camps in the Sinhala settlements, apart from the Seruwila Civil Security Department camp in Somapura. As of February 2020, there were several military checkpoints along the A15 road, the main thoroughfare that bifurcates this region.

Seven acres of land belonging to Tamils have been taken and turned into a naval camp near Verugal Muhaththuvaram. Although the landowners have the necessary documentation, their land has not been returned. The landowners told PEARL researchers that they have been prevented by the navy from even retrieving coconuts from the trees on their land. They also said that since the new government took power in November, navy officials have prevented the landowners from entering their land.

Two acres of land belonging to Tamils in Anaitivu, Vallaithottam have been used to establish an army camp and the people have been denied access.

A large navy camp, called SLNS Lankapatuna, is located just north of the new Buddhist temple at Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram.

A satellite camp is also located closer to the bridge leading to the temple.

The headquarters of the Sri Lanka National Guard’s 24 Battalion is located in Eachchilampattu.

The region covering what is now called Seruwila and Verugal has seen much change since Sri Lanka’s Independence. While the initial settlements of Sinhala colonizers in the 1950s faced some resistance from Tamil politicians, who argued it went against the Land Settlement Ordinance as preference was given to settlers from outside the province, incidents of confrontation and violence was rare until the 1980s. Once anti-Tamil pogroms erupted on a larger scale, Tamils in some areas were subjected to ethnic cleansing. In some villages the demographics shifted permanently, turning previously Tamil-speaking villages into entirely Sinhala ones. From the forced expulsion and massacres by the Sri Lankan armed forces against Tamils in the 1980s to the current occupation of religious sites, particularly in Ilankaithurai Muhaththuvaram and Kallady, the Sri Lankan state is continuing its project of Sinhalising the Trincomalee district in this area.25 The local population, which includes a Tamil-speaking Veddah minority, often themselves neglected by the Tamil community, feels the pressure of Sinhalization and continues to resist it. While the Seruwila Division has effectively been Sinhalised, in the Verugal Division, fear of Sinhalization and anger at the military occupation of land and the Buddhist occupation of traditionally Tamil places of worship is increasing.

Tamil Version of Infographic available here

Footnotes

1 Refugee Review Tribunal. (2005). Rrt Research Response.

3Yusoff, M.A. & Sarjoon, A. & Awang, A. & Hamdi, I. (2015). Land Policies, Land-based Development Programs and the Question of Minority Rights in Eastern Sri Lanka. Journal of Sustainable Development. 8. 10.5539/jsd.v8n8p223.

4Gaasbeek, T. (2010). Bridging troubled waters? : everyday inter-ethnic interaction in a content of violent conflict in Kottiyar Patty, Trincomalee, Sri Lanka.

7 UTHRJ. (n.d.). Colonisation & Demographic Changes in the Trincomalee District and Its Effects on the Tamil Speaking People. Retrieved from http://www.uthr.org/Reports/Report11/appendix2.htm

8LTTE Peace Secretariat. (2005). Demographic changes in the Tamil Homeland in the Island of Sri Lanka Over the Last Century.

9 Gaasbeek, T. (2010). Bridging troubled waters? : everyday inter-ethnic interaction in a content of violent conflict in Kottiyar Patty, Trincomalee, Sri Lanka.

10Devendra, T. (2006, August 6). Stuck in the Mud: Settling pioneers in Allai in 1953. Sunday Island. Retrieved from http://www.island.lk/2006/08/06/features4.html

11 Gaasbeek, T. (2010). Bridging troubled waters? : everyday inter-ethnic interaction in a content of violent conflict in Kottiyar Patty, Trincomalee, Sri Lanka.

12Hoole, R., 2001. Myth, decadence and murder: Sri Lanka – the arrogance of power.

13 Gaasbeek, T. (2010). Bridging troubled waters? : everyday inter-ethnic interaction in a content of violent conflict in Kottiyar Patty, Trincomalee, Sri Lanka.

14Admin, S. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved from http://seruwila.ds.gov.lk/index.php/en/common-details/population.html#population-by-ethnic

15 UTHRJ. (1996, March 5). Trincomalee District in February 1996: Focusing on the Killiveddy Massacre. Retrieved from http://www.uthr.org/bulletins/bul10.htm

16Gaasbeek, T. (2010). Bridging troubled waters? : everyday inter-ethnic interaction in a content of violent conflict in Kottiyar Patty, Trincomalee, Sri Lanka.

17 Jayasekera, K. D. (2003, September 8). The saga of Seruwila Mangala Viharaya. The Saga of Seruwila Mangala Viharaya. Retrieved from http://lankabhumi.org/seruwila.htm

18Centre, UNESCO. W.H. (n.d.). Seruwila Mangala Raja Maha Vihara. Retrieved from https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5083/

19 Gaasbeek, T. (2010). Bridging troubled waters? : everyday inter-ethnic interaction in a content of violent conflict in Kottiyar Patty, Trincomalee, Sri Lanka.

20 Tamil Guardian. (2016, August 16). From Ilankaiththurai to Lanka Patuna. Retrieved from https://www.tamilguardian.com/content/ilankaiththurai-lanka-patuna-0

22 PEARL Interviews 2020

24 Amazing Lanka. (2016, December 28). Pashana Pabbatha Rajamaha Viharaya. Retrieved from https://amazinglanka.com/wp/pashana-pabbatha-rajamaha-viharaya/

25LTTE Peace Secretariat (April 2008). Demographic changes in the Tamil homeland in the island of Sri Lanka over the last century.

—————————————————————————————————————–

Sinhalization of the North-East: Kokkilai

The Tamil villages of Alampil, Chemmalai, Nayaaru, Kanukerni, Kokkuthoduvaai, Karunaaddukerny and Kokkilai sit on a narrow strip of land, between the Indian Ocean and the lagoons of Kokkilai and Nayaaru, making up the Kokkilai region. The region saw seasonal Sinhala migration from the west coast of the island for decades.² In the past, a few Sinhala families would come and work with and alongside Tamil fishers and return to their west coast villages.³ This occurred without issues for many decades – the migratory practices were accepted by the Tamil community in the early years following independence.⁴

However, from the 1970s, the government encouraged the Sinhala migrants to settle permanently, promising them land and support.⁵ Furthermore, Sinhalese fishermen from other areas of the country, including owners of larger fleets, also arrived, putting the local Tamil fishermen under pressure and rising tensions between the communities.⁶

Although President Jayawardene in the 80s “pledged not to disturb the ethnic composition of the traditional Tamil homelands”, the structural realities differed.⁷ National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali announced in 1984 that the government would solve the “terrorist” problem by settling 200,000 Sinhalese in the North, drawn from groups such as convicted criminals.⁸ In December 1984, in what is termed an act of ethnic cleansing and genocide by the local population,⁹ the government forced all Tamils living in the old Tamil villages of Kokkilai, Kokkuthoduvaai, Karunaaddukerny, Nayaaru, Chemmalai, Kumulamunai and Alampil to leave their homes.¹⁰ The military used their vehicles to make announcements, demanding the Tamils leave within 24 hours.¹¹

Regular attacks on Tamils by the military followed over the months and years of war, resulting in hundreds of deaths. Tamils were also attacked when they returned to tend to their fields, preventing their resettlement.¹² Tamil militants attacked the Sri Lankan military and Sinhala settlers in response, killing dozens and displacing many more. As of February 1985, 10,000 Tamil and Muslim refugees from the villages of Kokkilai, Karunaaddukerny, Kokkuthoduvaai, Alampil, Nayaaru, Chemmalai, Kumulamunai, Aandankulam, Arumuganthankulam, Murippu and Thennaimaravadi, were in camps in Mullaithivu.¹³ Newspaper reports from the time say they were evicted in order to make room for Sinhala settlers, particularly in Kokkilai and Nayaaru.¹⁴

Buddhist Shrine in Kokkilai

Tamil pilgrims at the Neeraviyadi Pillayar Temple, destroyed and moved into the wall of the larger Buddhist temple.

Buddha Shrine in Koddaikerny

“The Government is determined that the Sinhalese presence in the northern and eastern provinces, claimed by the Tamils as their historic homelands, shall not be diminished. Indeed they are proposing to increase the proportion of Sinhalese in the area by establishing new settlements of southerners. The new settlers also will be armed and given weapons training. They are also likely to be recruited from prisons. The Tamils, recognizing this as a threat to the integrity of those areas they would like to make independent under the name of Eelam, are determined to fight the proposals.” The Times, 13 February 1985

“December 28, 29, 1984: Six Tamil women from Kokuthudavai and Kokilai reached a refugee camp in Mullaitivu complaining that they had been raped by army personnel. There are 21 Tamil refugee camps in the Mullaitivu area […] all chased away from their homes by the security forces.” Tamil Times, February 1985

As southern fishermen and their families were settled on the coast, some of the Sinhala fishermen were given guns used by Tamil farmers for agricultural purposes in the past. This happened on the instructions of the Ministry of Fisheries and the security forces, according to Minister Thondaman’s letter to President Jayawardene in early 1985.¹⁵ Furthermore, the Sinhala fishermen in Nayaaru and Kokkilai were given arms training by the security forces in Negombo. Minister Lalith Athulathmudali visited these settlements on January 15, 1985 and paved the way for further financial and material incentives for those who colonised these regions.¹⁶

Since the end of the armed conflict in 2009, the region has seen increasing tensions between Tamils who returned after displacement and Sinhala settlers, some of whom had by then lived in the area for many years and had solidified their presence. Local Tamils mainly complain about the proliferation of Buddhist structures, the heavy military presence, and the permanent settlement of Sinhalese fisher families by the state on their land. The often illegal occupation of Tamil lands has effectively rendered the social fabric of the space to substantial change. Those Tamils who were resettled back onto their respective lands found themselves having little to no access to basic facilities housing, sanitation, health care and education.¹⁷ Furthermore, religious repression by Sinhala Buddhist monks, with the support of the military, has also fueled anger amidst the population.

Signboard for the Guru Kanda Rajamaha Vihara, built on the site of a Hindu shrine.

Guru Kanda Rajamaha Vihara, with a signboard for the Neeraviyadi Pillayar Hindu temple.

MILITARISATION

1

2

3

There are at least seven army camps and five navy camps between Alampil and Kokkilai.

In Alampil, the site of an LTTE cemetery is now being used by the army. It was bulldozed after the loss of the LTTE in 2009. Today the site is occupied by the headquarters of the 24th Battalion of the Sinha Regiment and a “multi-shop”, open to the public, operated by the troops. On the coast not far from the camp, the battalion runs a holiday resort named “Green Jackets Resort”.

Further along the coast, in the village of Nayaaru, the 19th Battalion of the Gemunu Watch, has two camps, one built adjacent to a Buddhist temple site, disputed by the local Tamil population (See Buddhisization). The 593 Brigade occupies a large area here too, with a Buddha statue on its premises.

In Kokkuthoduvaai North, a large army complex occupies the junction where the roads leading to Manal Aaru/Weli Oya and Mullaithivu/Kokkilai meet. Here the 19th Battalion of the Gemunu Watch has their headquarters and operates a canteen and a fuel station. The 2nd Battalion of the Special Forces also have their headquarters nearby and operate a training school.

In Karunaaddukerny, the 19th Battalion of the Gemunu Watch operates a camp. Military barracks are also located on the main road in the village. The navy has at least five naval detachments in the area, including at Chemmalai, Nayaaru, Kokkuthoduvaai, and two in Kokkilai.

Army Canteen run by the 593 Brigade

Green Jackets Multishop – military-run business built on the site of an LTTE cemetery destroyed by the army.

BUDDHISIZATION

Guru Kanda Rajamaha Vihara, which was built on the site of a Hindu temple. A military camp is located opposite the new Buddhist complex.

Neeraveeyadi Pillaiyar shrine was a free-standing site of worship frequented by Tamils in the region. Tamils travelling to and from Chemmalai would stop and offer a prayer at the shrine before travelling on.¹⁸ Following the end of the armed conflict, an army camp was established on the site in Neeraveeyadi, Chemmalai, with the subsequent addition of a Buddhist statue. When the displaced Tamils returned to Chemmalai in 2012, they discovered that the Hindu shrine had been occupied. Efforts were made by army leaders to begin the building of the Buddhist temple. The commander of the 593 Brigade authorized the establishment of the Buddhist temple and it named Guru Kanda Rajamaha Vihara.

A Buddhist monk, Kolamba Medhalankara Thero, now resides in the facility originally occupied by the Tamil Hindu shrine.¹⁹ The monk claims that the site was originally home to a large Buddhist complex and that the Tamil shrine was built on top of it. However, a response from the Maritime Pattu Divisional Secretariat to a Right to Information request in 2018 shows that there was no Buddhist temple at the location and no Buddhists lived in this area. The Divisional Secretariat further said that no permission was requested prior to the construction of the Buddhist temple.²⁰

Court proceedings were initiated and in May 2019 it was held that both religious shrines should equally partake in faith-based activities.²¹ However, this decision was not accepted by the Sinhala Buddhist monk, who brought in Sinhala Buddhist worshippers to protest against this decision in June. In response, hundreds of Tamils gathered from across the Tamil homeland to attend Neerayaavedi’s temple’s “Festival of Resistance” in July this year.²²

Currently the Pillayar shrine occupies a small site on the outside of the Buddhist complex. While Tamils are able to access the location, tensions with the Buddhist monk and the military continue. The local community continues to demand the return of the land.²³

A Buddhist temple under construction on the site of a destroyed Hindu temple, on private Tamil land in Kokkilai.

The Arasadi Pillayar Hindu temple, located in Kokkilai, was destroyed during the war. Its site – on land situated between the local hospital and post office – was used to erect a Buddhist temple.²⁴ The owner of the land, T Mannivanathasan, filed a case against the illegal construction, which was upheld in 2015. In a letter to the Buddhist monk behind the illegal construction, the Divisional Secretary called for an end to all construction until the case was resolved. Despite this, construction of the Buddhist temple has continued intermittently.²⁵

SINHALA SETTLEMENTS

Sinhala fishing settlement in Kokkilai

After the forced expulsion of Tamils from Kokkilai in the 80s, Sinhala settlers from the south established further permanent settlements. When the Tamil population returned in 2011, two years after the end of the armed conflict, they found Mukaththuvaram, the area right on the tip of Kokkilai, to be settled entirely by Sinhalese. The Tamil fishermen faced harassment, including the destruction of their equipment, by Sinhala fishermen, monks and the police, when they attempted to engage in their trade.²⁶

In 2018 a court ruled that the land belonging to Tamils must be returned and defeated a claim by Sinhala fishermen for the coastal area in Kokkilai.²⁷ Despite the court order, the Mahaweli Authority and the Housing Development Authority, which both have more power than the local authorities, continued to issue permits and allocate housing schemes to Sinhala fisher families. Local Tamil politicians, including TNA MP Shanthi Sriskandarajah and former NPC Councillor T Ravikaran have vehemently opposed these moves.²⁸ Meanwhile, Sinhala Buddhist monks continue to call for the Sinhalisation of the area, as Tamils continue to block government moves to grab further land for settlements.²⁹

According to local officials, around 500 Sinhala families are now settled in this area. While Kokkilai Muhaththuvaram is the largest Sinhala settlement, further permanent settlements exist along the coast, including at Naayaru and Kokkuthoduvaai. However seasonal migration also still occurs.³⁰

“If there is no intervention, the damage… will be irreversible and irreparable,” TNA leader R Sampanthan, speaking in Chennai in 2014.³¹

The Kokkilai region has been contested for decades. While the seasonal migration of Sinhala fisher families seems to have occurred without many problems pre- and post-independence, the increasingly oppressive policies by the state, including colonisation schemes and violence against Tamils have made this area one of the most disputed regions in the North-East. The Sinhala fisher families are largely recent arrivals but also include those who have engaged in fisheries in this area for decades. From forced expulsion and massacres by the Sri Lankan armed forces against Tamils in the 80s to the current occupation of religious sites, the Buddhisization of the area and ongoing land grabs, the Sri Lankan state has maintained its project of Sinhalising this region – which, if successful, would drive a wedge between the contiguous Tamil-speaking areas, traditionally claimed as the Tamil homeland. However, the local Tamil community has repeatedly demonstrated their readiness to resist and protest these actions. The urgency of their call to halt Sinhalisation efforts must be heeded. Together with neighbouring Pulmoaddai, this region is arguably the most strategically important and economically viable area for the Tamil-speaking people. The pressure of Sinhalisation is felt acutely here. Without a meaningful resolution to Tamil grievances, one that also considers the future of those Sinhala settler families, the potential for further conflict continues to grow.

View the full report as a PDF here.

Footnotes

The Breakup of Sri Lanka: Tamil-Sinhalese-Tamil conflict; A Jeyaratnam Wilson, 1989 (p 37)

PEARL Interview with K Ravikaran, September 2019

PEARL Interview with K Ravikaran, September 2019

“Land in the Northern Province”; B Fonseka, M Rahim; Centre for Policy Alternatives; 2011

“Genocide against the Tamil People: STATE AIDED SINHALA COLONISATION”; International Human Rights Association Bremen – People’s Tribunal Sri Lanka, 2013; (accessed at http://www.ptsrilanka.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/state_aided_sinhala_colonisation_en.pdf

);

);Tamil Times, December 1984

The Breakup of Sri Lanka: Tamil-Sinhalese-Tamil conflict; A Jeyaratnam Wilson, 1989

“Mahaveli System L: The Weli Oya Project And The Declaration Of War Against Tamil Civilians”; Rajan Hoole, Colombo Telegraph, 2014; (accessed at https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/mahaveli-system-l-the-weli-oya-project-and-the-declaration-of-war-against-tamil-civilians/)

PEARL Interview, July 2019

“Mahaveli System L: The Weli Oya Project And The Declaration Of War Against Tamil Civilians”; Rajan Hoole, Colombo Telegraph, 2014; (accessed at https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/mahaveli-system-l-the-weli-oya-project-and-the-declaration-of-war-against-tamil-civilians/)

“Special Report 5”; UTHR-J, 1993 (accessed at http://www.uthr.org/SpecialReports/spreport5.htm); https://jaffnazone.com/news/2684

S Thondaman – March 1985

Tamil Times, March 1985; The Times (UK), 13 February 1985;

Ibid

S Thondaman – March 1985

Tamil Times, March 1985

“Situation in North-Eastern Sri Lanka: A series of serious concerns”; MA Sumanthiran, 2011 (accessed at http://dbsjeyaraj.com/dbsj/archives/2759);

“நீராவியடி பிள்ளையார்” [Video]; IBC Tamil, 2019 (accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2dpI2bFzq84)

“Occupying Colombo schemes Sinhala Buddhist settlement in Chemmalai-East, Vanni”; TamilNet, 2019 (accessed at https://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=79&artid=39477);

“Occupying Colombo schemes Sinhala Buddhist settlement in Chemmalai-East, Vanni”; TamilNet, 2019 (accessed at https://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=79&artid=39477);

‘Buddhist monk files High Court appeal against Mullaitivu Tamil temple”; Tamil Guardian, 2019 (accessed at https://www.tamilguardian.com/content/buddhist-monk-files-high-court-appeal-against-mullaitivu-tamil-temple)

“Hundreds attend Neeraviyadi temple’s Pongal ‘festival of resistance’”; Tamil Guardian, 2019 (accessed at https://www.tamilguardian.com/content/hundreds-attend-neeraviyadi-temples-pongal-festival-resistance);

PEARL Interviews, July-September 2019;

“Situation in North-Eastern Sri Lanka: A series of serious concerns”; MA Sumanthiran, 2011 (accessed at http://dbsjeyaraj.com/dbsj/archives/2759);

“Buddhist monks oversee vihara construction in Mullaitivu”, Tamil Guardian, 2016; (accesssed at https://www.tamilguardian.com/content/buddhist-monks-oversee-vihara-construction-mullaitivu); “Kokkilai Buddhist temple issue”, IBC Tamil , 2016; (accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9IBCv5chFrs);

“Sinhala Buddhist monks and Sri Lankan police threaten Tamil fishermen”, Tamil Guardian, 2016; (accessed at https://www.tamilguardian.com/content/sinhala-buddhist-monks-and-sri-lankan-police-threaten-tamil-fishermen?articleid=22326); “Braving threats, Tamil fishermen return to Kokkilai”, Tamil Guardian, 2016; (accessed at https://www.tamilguardian.com/content/braving-threats-tamil-fishermen-return-kokkilai);

“Mullaitivu court rules against Fisheries Department and declares contested coastal land belongs to Tamil fishermen”, Tamil Guardian, 2018; (accessed at https://www.tamilguardian.com/content/mullaitivu-court-rules-against-fisheries-department-and-declares-contested-coastal-land)

“Tamil politicians object to Sinhalese housing scheme in Kokkilai”, Tamil Guardian, May 2019; (accessed at https://www.tamilguardian.com/content/tamil-politicians-object-sinhalese-housing-scheme-kokkilai); “Mullai GA gives in to pressure from top, allocates lands to Sinhala colonists”, TamilNet, May 2019; (accessed at https://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=13&artid=39446); “Mahaweli Authority issues land permits to Sinhalese settlers in Mullaitivu, defying court order”, Tamil Guardian, July 2018; (accessed at https://www.tamilguardian.com/content/mahaweli-authority-issues-land-permits-sinhalese-settlers-mullaitivu-defying-court-order);

“Sinhala Buddhist monk calls for continued militarisation and Sinhalisation in Mullaitivu”, Tamil Guardian, January 2019; (accessed at https://www.tamilguardian.com/content/sinhala-buddhist-monk-calls-continued-militarisation-and-sinhalisa

https://pearlaction.org/2019/09/21/sinhalization-of-kokkilai/

Sinhalization Of The North East: Pulmoaddai

by People for Equality & Relief in Lanka, March 11, 2019

Pulmoaddai is a majority Tamil-speaking, Muslim town in the Trincomalee District. The town, part of the Kuchchaveli Divisional Secretariat, is located on the border to the Mullaithivu District, occupying the strategically important region which links the traditional Tamil homeland’s northern and eastern regions. The area is known for its valuable mineral deposits, including ilmenite, rutile and zircon, which are mined by a state-owned company. According to locals the vast majority of employees in this company are from the south. Mining was halted during the war after the LTTE attacked ships carrying the deposits, saying it was an important natural resource of the Tamil homeland. Local activists have expressed concerns that the region is not benefiting from the exploitation of its resources.

The Muslim population in Pulmoaddai has complained of Sinhala colonisation in surrounding areas, particularly since the end of the armed conflict in 2009. The expansion of Sinhala settlements, including along the B60 road and on land owned by Muslims, has alarmed the local population and increased tensions. The proliferation of military camps and Buddhist temples, on top of the settlements, are perceived by locals to be part of a wider effort to Sinhalise the region – dividing the previously contiguous Tamil-speaking populations on the Mullai-Trinco border.

The area is home to the Buddhist monk Thilakawansa Nayaka, a native of Hambantota currently based in Arisimalai, just south of Pulmoaddai town. According to Muslim and Tamil residents, the monk is behind the establishment of the Buddhist temples and Sinhala settlements in the region. He is currently engaged in appropriating land in Pulmoaddai and Thennaimaravaadi for the purpose of constructing Buddhist structures.

A Right to Information request reveals that these settlements were constructed with the consent of the National Housing Development Authority. However, the Kuchchaveli Divisional Secretariat confirmed that they did not give permission and that they had given notice to vacate to those who intruded on the land. See full RTI response here

. This confirms suspicion by locals that the state acts in contravention of the local authority.Militarization

The security forces have large camps in the area, including those belonging to the Army, Navy and the Special Task Force. A map of the area shows the encirclement of Pulmoaddai by the Sri Lankan security forces, in all three directions.

To the north, the Navy camp SLNS Ranweli occupies one of the few roads leading to the coast. The camp was built after the end of the armed conflict on land originally owned by civilians. Another small navy outpost is located right on the coast, across Kokkilai town on the other side of the lagoon.

Further east on the B70, closer to the 13th Milepost, the 27 Battalion of the Gajaba Regiment is deployed in a camp.

South of Pulmoaddai, the STF occupies a large camp, while the Gajaba Regiment’s 27th Battalion B Company also has a camp in the area.

On the southeastern boundary of Pulmoaddai town lies Arisimalai, the location of a Buddhist complex, that can only be accessed with permission from the Naval Subdetachment Arisimalai. Another larger Navy camp is located around 200m further down the road.Buddhisization

Many of the military camps are located close to or even adjacent to Buddhist structures. In at least one case, the Navy camp Ranweli, the Buddhist Vihara has been constructed by navy personnel, on the land opposite their camp. Like the camp, this Vihara is also constructed on private land.

The 27th Battalion of the Gajaba Regiment’s camp is also located a short distance away from the temple constructed near the “Shanthipura” Sinhala settlement. Satellite imagery shows how the Buddhist pansala at “Shanthipura” in 2011 preceded the settlement of Sinhala civilians in the vicinity.

Arisimalai has seen a special focus by Buddhists, due to the presence of ancient ruins. Located in a majority-Muslim and entirely Tamil speaking area, it has seen the construction of a Buddhist temple and adjoining retreat, called Asiri Kanda Purana Rajamaha Viharaya on top of a hillock overlooking the beach. Access to the site is controlled by a Navy camp. The temple was constructed after claims that Buddhist artefacts were found, resulting in the government giving 500 acres for the temple in the early 80s. The aforementioned monk Thilakawanse Nayaka is the chief incumbent of the temple. In 2018 the monk complained about local people encroaching on temple land, and demanded more protection for the area. An official from the Archaeological Department, responsible for the region, also complained about Hindu temples being built and visited by locals. District Secretary Pushpakumara Nissanka said that the Arisimalai Temple has been requesting 500 more acres to be given to the temple premises, and that they decided to grant 25 acres under the religious lands act, while declaring 500 acres as an Archaeological Forest Reserve.

Several Buddhist shrines are dotted around the area. On a cliff, overlooking Pulmoaddai town and the Indian ocean, foundations have been laid for a large stupa.

Arisimalai is a fishing village, renowned for its beach’s large-grained sand (Arisi – rice in Tamil). PEARL researchers visited the area in December 2018 and January 2019. A sign by the Department of Coastal Conservation at the entrance of the path leading to the hill and the beach, warns visitors to abide by rules for the “ancient, sacred area”, including entering the jungle as it “disturbs monks who are meditating”. The path is only accessible with permission by the navy camp. The navy personnel stationed at the checkpoint prohibited us from taking our car up the path, saying that all vehicles had to be parked near the entrance. However, as we walked, a group of Sinhala pilgrims passed us in their van. Buddhist shrines were dotted along the path, which lead to a clearing on an elevation overlooking the Indian Ocean, where the construction of a stupa commenced recently.

Climbing down from the cliff, we reached Arisi Malai beach. The sand really was like rice. As we walked around, we could see the Buddhist temple in the forest, south-west of the beach. We climbed up towards it, passing a meditation bench overlooking the beach and a monk’s rest house. Here the paths were well-demarcated and clean. Signs in Sinhala and English warned against following some paths, saying they are only open to “venerable monks”. Walking further, we reached the temple. The Sinhala pilgrims we saw earlier were giving offerings to a monk, giving us uneasy looks. We hurried past them. As we walked back, we saw the Sinhala van parked right next to the temple.

Sinhala Settlements

The demographics of the wider region have seen a drastic increase in the Sinhala population starting prior even to the outbreak of war, particularly in the Padavi Sri Pura region of Trincomalee and the Manal Aaru (Weli Oya) region of Mullaithivu. Pulmoaddai, which occupies the North of the Trincomalee district, has seen more recent settlements established in Maalanoor at the 12th mile post and near Eramadu, at the 10th milepost, including on land owned by Muslims. Settlers who spoke to PEARL in Maalanoor in January 2019 said that they came from Galle, in the south of the country. They call the settlement “Shanthipura”. The road on which the two settlements are located is home to Buddhist temples, several statues, and a meditation centre, which also functions as a base for the archaeological department.

Another statue was completed recently near Eramadu. Google streetview images from 2016 show a small shrine and few makeshift houses, while a February 2019 visit to the area found a larger newly built structure on the same site and an expansion of the settlement into proper houses.Buddhists are also claiming sites in Thennaimaravaadi, northwest of Pulmoaddai, for Buddhist temples. One site is situated on the road linking Trincomalee to Mullaithivu. The location used to be home to a military camp, which was dismantled. However, soldiers left behind a bo tree, which is sacred to Buddhists and often grounds for the declaration of a sacred Buddhist site. The monk Thilakawansa has claimed the location for the construction of a Buddhist temple, despite objections by the local population. No construction has commenced on either site so far. Another site is being claimed by the Department of Archaeology on a hilltop in Thennaimaravaadi. The location was home to a Murugan temple until the villagers were chased out in 1984 by the Sri Lankan Army. On their return, they found the Hindu temple destroyed. The Department of Archaeology declared the area out of bounds, claiming it was a historic site. In 2018 villagers protested against any attempt to construct a Buddhist statue on the hilltop, demanding the return of the land in order to resume worship. No construction of Buddhist structures has commenced on either site so far.

Another statue was completed recently near Eramadu. Google streetview images from 2016 show a small shrine and few makeshift houses, while a February 2019 visit to the area found a larger newly built structure on the same site and an expansion of the settlement into proper houses.Buddhists are also claiming sites in Thennaimaravaadi, northwest of Pulmoaddai, for Buddhist temples. One site is situated on the road linking Trincomalee to Mullaithivu. The location used to be home to a military camp, which was dismantled. However, soldiers left behind a bo tree, which is sacred to Buddhists and often grounds for the declaration of a sacred Buddhist site. The monk Thilakawansa has claimed the location for the construction of a Buddhist temple, despite objections by the local population. No construction has commenced on either site so far. Another site is being claimed by the Department of Archaeology on a hilltop in Thennaimaravaadi. The location was home to a Murugan temple until the villagers were chased out in 1984 by the Sri Lankan Army. On their return, they found the Hindu temple destroyed. The Department of Archaeology declared the area out of bounds, claiming it was a historic site. In 2018 villagers protested against any attempt to construct a Buddhist statue on the hilltop, demanding the return of the land in order to resume worship. No construction of Buddhist structures has commenced on either site so far.

Pulmoaddai is only one of several locations in the North-East in which Tamil-speaking people have expressed concerns about the government’s deliberate efforts to change the demographics of the region. Since the end of the armed conflict in 2009, the government has constructed at least four navy camps, two army camps, and one Special Task Force camp in Pulmoaddai, including on private land. The proliferation of military camps has often gone hand-in-hand with the construction of Buddhist sites. Our research found at least ten Buddhist structures, some directly linked to a military facility, in the area. The presence of the Buddhist monk Thilakawansa in Arisimalai, coupled with his aggressive, expansionist policies that extend beyond Pulmoaddai, have raised more concerns among the local population. The National Housing Development Authority has also constructed Sinhala settlements in two locations over the last ten years. A Right to Information (RTI) response by the Kuchchaveli Divisional Secretariat stated the settlements were built without the local authority’s permission. The National Housing Development Authority built these houses for Sinhala settlers despite the eviction notices served to the settlers by the Divisional Secretariat. Local Muslim farmers who have traditionally cultivated the area are continuing to resist the increasing settlements on their land. The strategically important area linking the Tamil-speaking-majority provinces of the north and east have been targeted for Sinhalization for decades. This has raised tensions in the region beyond Pulmoaddai. Failure to address the concerns of the local population about these changes risks turning the area into a potential flashpoint. A Muslim civil society leader told PEARL in August 2018: “We will not sit by idly while the state attempts to make our land Sinhalese. Today they have taken our farm land; tomorrow they will take our homes. If the government was serious about peace, they would not do this.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.