Ilankai Tamil Sangam

25th Year on the Web

Association of Tamils of Sri Lanka in the USA

Sri Lankan Tamil Struggle

Chapter 17

The Arunachalam Factor (Continued) by T. Sabaratnam, December 8, 2010

A journalist who reported Sri Lankan ethnic crisis for over 50 years

Sabapathy told the others that he would, in the interests of national unity, accept territorial representation, if the number of Tamil representatives was increased.

Encouraged by Sabapathy’s change of stand from communal representation to territorial representation Arunachalam started a campaign to promote the formation of a common organization. In September 1918 he delivered an address on the “Present Political Situation”. In that he made a clarion call for constitutional reform and self-government.

Arunachalam like his brother Ramanathan believed in Sri Lankan nationalism and laid his trust on Sinhala elites until he was let down by them. He tried his best to build a united Sri Lanka in which Sinhalese and Tamils as ‘founding communities’ would share power. Like Ramanathan he was also influenced by his family members and the Indian independence movement.

Born and brought up in the Colombo Tamil elite Coomaraswamy family, educated at Royal College along with the children of the families of Sinhala elites and later at Cambridge where he moved with the nobles and liberals he was moulded into a liberal minded constitutional reformist and a nationalist with a broad vision.

The orthodox Saivaism his family practiced, the independence his uncle Sir Muttu Coomaraswamy and his elder brothers Coomaraswamy and Ramanathan adopted in their activities in the Legislative Council and the influence the Indian independence movement had on him shaped his political activities.

Arunachalam had a wide awareness of, and deep sensitiveness to, the problems of the underprivileged. He displayed a genuine interest in their conditions of existence. His interest in the common man was the result of his moving in interesting circles which included liberal thinkers during his Cambridge days. He got interested in political reform by following keenly the reforms effected by British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli who during his first term as prime brought about changes in the qualification for being a voter.

Arunachalam got interested in the problems of the underprivileged by following the laws Disraeli enacted during his second term as prime minister which began in 1874. Disraeli’s laws dealt with the improvement of the conditions of dwellings of factory workers and raising the standard of public health. He also enacted the Food and Drugs Act. Disraeli was a friend of Sir Muttu Coomaraswamy who greatly influenced Arunachalam’s life.

Arunachalam’s letters to the editor sent to John Ferguson, urging Ferguson to convene a conference of public men to discuss political reforms were born out of his thinking in terms of the country. From 1906 to 1913 the periods in which he was in the Legislative Council as a nominated member and then in the Executive Council due to his being the Registrar General he adhered to the family tradition and served the British rulers loyally. He turned social reformer and political activist after his retirement in 1913 when he was knighted for distinguished service to the British Crown. He received his reward from King George V at Buckingham Palace.

Arunachalam lived eleven years after he was knighted. Of that period he spent the first seven years- 1914 – 1920- working feverishly for the political advancement of the county. He also made some effort to improve the lot of the common man. Being influenced by Disraeli’s work to help Britain’s exploited factory workers Arunachalam elected to improve the appalling conditions of the plantation workers. He formed the Ceylon Workers Welfare League in 1915 of which he was the president. Periannan Sundaram popularly known as Peri Sundaram , the first Tamil of the Indian origin to graduate from Cambridge University, became the secretary. In the First State Council Peri Sundaram served as the Minister of Labour and played a leading role in promoting the welfare of the plantation workers.

In Chapter 10 I gave the circumstances in which Indian Tamil labour came to Sri Lanka. They came to work in the coffee plantations since 1830s during the picking season and returned to their villages when the season was over. I said the situation changed in 1870s when coffee plantation industry collapsed due to the leaf disease. Planters experimented with various plantation crops but tea and later rubber took the place of coffee.

With the introduction of tea and rubber the labour requirement of the plantation industry changed. It required resident labour to pluck tea leaves and tap rubber. Planters preferred labour families where males and females could work. Migration of family units became the rule. This resulted in a sudden influx of Indian Tamils into the estates. The following statistics illustrate the growth of the estate population during that period:

1881 206,840

1891 262,262

1901 441,523

1921 600,000

1939 1,000,000

As I have already pointed out, majority of the workers came to Sri Lanka under the kankarny system and the rest came on their own. As the extent of the areas under tea and rubber expanded the need for labour grew faster than the rate of immigratioon. This created a situation where new estates offered better wages and other facilities and attracted the workers from other estates. Individual labourers and kankarnies with their gang of workers went from estate to estate. This was called ‘bolting.’

Under pressure from the Planters Association of Ceylon the government enacted a series of ordinances beginning in 1841 to prevent bolting. The object of the 1841 ordinance stated that it was enacted “For the better regulation of Servants, Labourers and Journeymen Artificers under contracts of Hire and Service and their Employers.” Though it was sophistically worded the intention of the ordinance was to prevent Indian Tamil plantation labourers deserting the employer who got them down from India and joining another. This ordinance virtually bonded the labourers to the estate.

The series of amendments made to the 1841 ordinance tightened the hold of the employer on the labourers. All those ordinances were updated in 1865 and under that ordinance bolting from the estate to which the labourers came was made a penal offence. A labourer who ran away from the estate in which he was employed could be arrested and tried before a court of law. The magistrate had the power to impose a fine on the offender or sentence him to prison.

The planters were not satisfied even with the 1865 ordinance because bolting still continued. On their pressure amendments were made to tighten the law further. The amendments enacted in the years 1889, 1890 and 1902 led to the infamous Tundu System. It was also known as the Tin Ticket System.

The map shows the route the immigrant Tamil labourers walked from Mannar to Kandy. After the construction of the railway line they were taken to Colombo along the coast and then taken to the station close to the estate.

Under the Tundu System the labourers recruited for a particular estate were taken by the recruiter to Mandapam, India Quarantine Camp for medical check up and then taken to Dhanuslody or Rameswaram. From there they were transported by boats to Mannar. At Mannar each labourer was given a number and the first letter of the name of the estate. They were inscribed on a tin ticket (a small piece of tin sheet) and hung from the labourer’s neck. That Tundu bound the labourer to the estate which recruited him. The Tundu System reduced the Indian Tamil labourer to the status of a slave.

The Tundu System was very unpopular from the beginning. Arunachalam and Ceylon Workers Welfare League campaigned for its abolition. Arunachalam who called it a “new form of slavery” took up the matter with the governments of Sri Lanka and India. Indian government took up the matter with Sri Lanka in 1921 and the ordinance was repealed.

Ramanathan’s Insulting Comment

Before I complete the story about Arunachalam’s effort to alleviate the plight of the Tamil estate workers I wish to give you the blunder Ramanathan made. I was wrong when I said in the last chapter that Ramanathan’s opposition against the grant of an unofficial seat for the Muslims in the Legislative Council was his first error. It was his second. Before that on January 4, 1884 in his speech in the Legislative Council he derogatively called the Tamil estate workers “coolies” and “Tamil coolies”. In six sentences he used the “coolies” five times and the words “Tamil labourers” only once.

The following excerpt is from his speech:

My honourable friend, the member for the planters, say that the Government ought not to interfere because the condition of the coolies was never better than it is now. I quite concede the fact that the Medical Aid returns furnished by the medical officer show that the sanitary state of the coolies to be very satisfactory, but that only proves that the coolie has adapted himself to the climate of the hills. This, however, does not disprove the necessity for Government interference. The Government is anxious to interfere, because the coolies do not receive their just dues at the present day…

I am not going to asperse the character of the planters. They have hitherto treated the Tamil labourer kindly and well and nobody who has not seen the Tamil coolie in his home in India can appreciate the ease and comfort which he enjoys in Ceylon.

Ramanathan had in several occasions spoke in support of the Indian Tamil plantation workers. On October 9, 1879 he spoke in the Legislative Council criticizing the Coffee Stealing Ordinance of 1876. He asked the Government to produce the statistics concerning the number of persons convicted of stealing coffee and the quantity of coffee that was stolen. He argued that the statistics would prove the harshness of the regulation.

On October 4, 1882 when the Sinhalese representatives criticized the employment of Tamil labourers in the plantations Ramanathan defended them pointing out that they were hard working. He concluded his speech saying,

It is very gratifying to see the Sinhalese, the masses, I mean, catch some of the bold spirit and enterprise of their fellow countrymen, the Tamils.

Though Ramanathan had fought for the Tamil labourers his use of the word “coolie” is sill remembered by the plantation Tamils and held against the Jaffna Tamils.

Thondaman in his autobiography “My Life and Times” has said (Page 96),

It has always surprised me how any Tamil could refer to the Tamils who had been brought to Ceylon to work in the plantations in the way Ramanathan did.

Thondaman was full of praise for Arunachalam. He says Arunachalam took “genuine interest” in the welfare of the plantation labourers. He adds that Arunachalam was a “solitary exception” in that period.

Arunachalam started campaigning against Indian Labour Ordinance and against the low wages and bad conditions in plantation soon after his retirement in 1913. Soon after the formation of the Ceylon Workers Welfare League he highlighted the inequities of the Master and Servants Ordinance of 1865 and its amendments. Under these ordinances plantation workers could be charged in a court of law for breach of contract and returned to their former employees, if they left their original estate. In 1916, he spoke against the conditions of the Indian Tamil laborers holed in the estates calling their lot was not an enviable one. He wrote,

Being poor, ignorant and helpless, he is unable to protect himself against the cupidity and tyranny of the unscrupulous recruiters and bad employers…

Arunachalam did not limit his interest only to plantation workers. He was sensitive to the problems of the underprivileged people of the country. He displayed a genuine interest in their conditions of existence. In a letter to Lord Chalmers, the Governor-designate of Ceylon, in July 1913, he drew attention to the burdens that the poll-tax imposed on the poor:

The rich are fortunate in Ceylon for they pay nothing else except on luxuries. The poor are unfortunate because they pay duty even on salt which is a Government monopoly. The rich, who as tea and rubber planters and in the professions, make large incomes and the Companies which make and send out of the Colony huge profits remain untouched. There is no income tax or land tax. I cannot help thinking about the miserable conditions of the poor.

This sensitivity to the problems of the underprivileged led to his joining with Sir James Peiris and founding the Ceylon Social Service League. At an exploratory meeting which preceded the formation of this League he emphasized the need to take steps to educate the masses, provide them with medical relief and better housing and establish a system of compulsory insurance and the payment of minimum wages.

Arunachalam did not have much time to continue his work for the betterment of the underprivileged. As one born into a political family and as one interested in the Indian freedom movement Arunachalam plunged headlong into Sri Lankan constitutional reform movement.

Formation of Ceylon National Congress

Arunachalam was interested in constitutional reforms even before he persuaded John Ferguson to publish his letters in 1902. In November l 875, the year he joined the Ceylon Civil Service, Arunachalam wrote a letter to the Editor of the Ceylon Observer under a pseudonym in which he deplored the exploitation practiced by the British rulers. It was their duty he argued to train Sri Lankan people to rule themselves. “I hope”, he added “that our race and religious differences here and in India will be at no far off time crushed into a national unity by the pressure of the stronger.”

The Ceylon Observer Editor A.M. Ferguson, John Ferguson’s uncle, considered the letter too radical to publish. Eleven months later, Arunachalam sent the rough draft of this rejected letter to his friend Digby for his information. In 1893 Arunachalam wrote to Digby urging him to impress upon the Secretary of State for the Colonies (a friend of Digby) the need to extend the principle of local self-government in Ceylon.

Arunachalam involved himself with zest in the agitation for political reform soon after his retirement in 1913. As one who followed the developments in India he was influenced by the Indian National Congress sessions held in Madras during December 28-30, 1914, the debate that took place in the sessions between the moderates and the radicals and the resolution passed requesting representation in the legislative bodies. He was equally influenced by the return of Gandhi and his wife Kasturba from South Africa to India in January 1915. Gandhi’s meeting with Rabindranath Tagore and his speeches on nonviolence and on the need for self government for India during his three week stay in Madras beginning April 17, 1915 left indelible imprint on him.

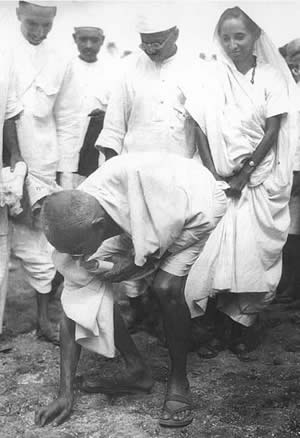

Gandhi and Kasturba after their arrival in January 1915 in Bombay harbour

Tamil and Sinhalese elites with whom Arunachalam associated were also influenced by the Indian events. The impact of those events led to the formation of the Ceylon Reform League on May 17, 1915. Its objective was to agitate for self-rule for Sri Lanka using the constitutional process as the vehicle.

Arunachalam was indignant at the manner in which British authorities handled the riots that broke out by the end of that month between the Sinhalese and the Muslims. On July 6,1915 he wrote to the Governor requesting the appointment of an impartial Commission of Inquiry. He kept in close touch with his friends at the Colonial Office in London acquainting them at every stage with what he regarded as being the true facts.

The Montagu Declaration of 1917, which had proposed the progressive development towards self-government in India, kindled the imagination of leaders in Ceylon. In World War I, the British claimed that they stood for the protection of democracy around the world. Thus the Indians, who fought for them in this war, demanded that democracy should also be introduced in their country. In his famous August Declaration presented before the House of Commons on August 20, 1917, Montague, the Secretary of State for Indian Affairs said that in order to satisfy the Indian demands, his government was interested in giving more representation to the natives in India. New reforms would be introduced in the country to meet this objective. He came to India and stayed there for six months. During this period he held meetings with different government and non-government people. Finally, in cooperation with the Governor General Lord Chelmsford, Montague presented a report on the constitutional reforms for India in 1918. The report was discussed and approved by the British Parliament and then became the Act of 1919. This Act is commonly known as Montague-Chelmsford Reforms.

The Act provided for the establishment of a Council of the Secretary of State comprising eight to 12 members of whom three should be Indians. The Secretary of State should follow the council’s advice. In addition it provided for the Central Legislative to have two houses: Council of the State (Upper House) and the Legislative Assembly (Lower House).

The Council of State was to consist of 60 members out of which 33 were to be elected and 27 nominated by the Governor General. The Legislative Assembly was to consist of 144 members out of which 103 were to be elected and 41 to be nominated by the Governor General. The franchise was limited. The tenure of office of the Council of State was five years and of the Legislative Assembly three years. Provincial legislatures were also to be established. They were unicameral.

The Montague-Chelmsford reforms were not accepted by most quarters in India as they fell far short of the Indian natives’ expectations.

Three months before the Montague Declaration Arunachalam demanded self-government for Sri Lanka. In his address in April 2,1917 on the topic “Our Political Needs” Arunachalam said,

The inherent evils of a Crown Colony administration remain. We are deprived of all power and responsibility, our powers and capacities are dwarfed and stunted, we live in an atmosphere of inferiority, and we can never rise to the full height to which our manhood is capable of rising.

The Legislative Council, as it is at present constituted, hardly answers a useful purpose. It provides, no doubt, seats of honor to a few unofficials and an area for their eloquence or for their silence. But they are little more than advisory members and their presence in the council serves to conceal the autocracy under which we live. The swaddling clothes of a Crown Colony administration are strangling us. They have begun even to disturb the equanimity of our European fellow subjects. None are safe until all are safe.

We ask to be in our own country as self-respecting people – self-governing, strong, respected at home and abroad, and we ask for the grant at once of a definite measure of progressive advance towards that goal. Ceylon is no pauper begging for alms. She is claiming her heritage.

Arunachalam’s address generated a great deal of interest among the Sinhala and Tamil elites and several lectures and conferences were held to discuss the demands to be placed for the consideration of the British government. The Ceylon National Association which was not functioning for a long time was revived by James Peiris in 1916.

On the advice of Arunachalam the Ceylon Reform League and Ceylon National Association invited the Jaffna Association and the Chilaw Association for a joint meeting to draft a common memorial to be presented to the British government. The first round of the joint talks was held at Victoria Masonic Hall on December 5, 1917. Arunachalam was unanimously elected president. In his Presidential Address, Arunachalam said,

The time is therefore auspicious to win for ourselves as large a measure of constitutional reform as possible.

We demand the liberty to take our share in the burden of this responsibility, to manage our own lives, make our own mistakes, gain strength by knowledge and experience, and acquire that self confidence and self respect which are indispensable to national progress and success. We seek to be in our own country what other self-respecting people are in theirs, self-governing, strong, respected at home and abroad, and we ask for the grant at once of a definite measure of progressive advance towards that goal.

The meeting decided to make the following demands: indigenous representation in the Legislative Council should be increased; all the indigenous representatives should be elected through territorial electorates; elected representatives should be included in the Executive Council; Legislative Council should be given full responsibility to control local and municipal councils and all senior positions in the government sector should be reserved for the local people.

A. Sabapathy

During the discussion A. Sabapathy, president of the Jaffna Association and a member of the Legislative Council, objected to the proposal that “all the indigenous representatives should be elected through territorial electorates” saying that would drastically reduce Tamil representation. He also wanted the Tamils to be allocated a larger share and Tamil members too be elected through communal electorates.

Delegates of the Ceylon National Association and Ceylon Reform League insisted on the demand for territorial representation. On Arunachalam’s suggestion a subcommittee was appointed to draft the memorandum embodying the demands accepted by the meeting. The subcommittee was also authorized to look into Sabapathy’s objection.

Arunachalam Sabapathy (1853–1924), born into a wealthy trading family of Thalaiyali, Vannaponne East was an influential journalist and educationist. a founding member of the Saiva Paripalana Sabhai, a member of the Jaffna Local Board, editor of Hindu Organ since its inception, one of the founders of Jaffna Hindu College, manager of the Hindu Colleges Board from 1913 and founder secretary of the Jaffna Association.

The subcommittee which drew up the draft memorandum decided that the Legislative Council should have 21 local representatives. The discussion on the sharing the representatives between the Sinhalese and the Tamil ended without a final decision. Sinhalese suggested that four of the representatives should be elected on communal basis and the balance 17 on territorial basis. The four communally elected representatives should be allocated to: two for Europeans and one each for Burghers and Muslims. Of the balance 17 representatives 13 should be allocated to the Sinhalese and four for the Tamils. Of the four Tamil representatives three would go to the Northern Province and one for the Eastern Province.

Sabapathy who acted as the chief spokesman of the Tamils objected to the proposal saying that the Tamils who wanted to negotiate separately with the British would never agree to such little representation. He also insisted on communal electorates for the Tamils.

The Sinhalese insisted that their offer of 13 to 4 was more than what the Tamils are entitled to on the basis of their population. They relented after much bargaining and offered one more seat for the Tamils. They increased the number of seats reserved for the Tamils in the Eastern Province to two thus increasing the number of Tamil representative to five. They insisted on their opposition to communal representation. Sabapathy still kept to his objection. The meeting ended without the Tamil issue unresolved.

The Assurance Given to the Tamils

Arunachalam did not give up his effort to form a common organization. In order to resolve the dispute between the Sinhalese and the Tamils he negotiated with James Peiris, president of the Ceylon National Association, and E.J. Samarawickrama who succeeded him (Arunachalam) as the president of the Ceylon Reform League about finding a solution to the dispute. He also arranged a meeting among Sabapathy, James Peiris and Samarawickrama. Sabapathy told the others that he would, in the interests of national unity, accept territorial representation, if the number of Tamil representatives was increased.

Encouraged by Sabapathy’s change of stand from communal representation to territorial representation Arunachalam started a campaign to promote the formation of a common organization. In September 1918 he delivered an address on the “Present Political Situation”. In that he made a clarion call for constitutional reform and self-government.

Arunachalam also negotiated on the basis of Sabapathy’s offer and persuaded James Peiris and Samarawickrama to concede the Tamils another seat in the Western Province where Tamils lived in significant numbers. They agreed to allocate the Colombo Town electorate. James Peiris and Samarawickrama gave this pledge in writing in the letter they wrote to Arunachalam on December 7, 1918.

The text of the letter:

Ceylon Reform League,

12, De Soysa Buildings,

Slave Island,

7th December 1918

Dear Sir Arunachalam,

With reference to the suggestion of Mr. Sabapathy that the words “on the basis of the territorial electorate” be omitted from Resolution 4, we shall be obliged if you will point out to him that their omission will seriously affect our case for the reform as a whole. We beg to remind him of all that the promoters of the Reform Movement have said of the baneful effect of the present system of racial representation.

We have made the territorial electorate a fundamental part of our demands. The omission of the words especially after the publication of the draft resolutions will be construed a surrender of an important principle.

It must be borne in mind that the resolution contain only the essential principles which we desire to assert. They do not constitute the complete scheme, and while we desire to avoid the introduction of details into the resolutions, we are anxious to do all that could be done to secure as large a representation as possible to the Tamils, when exceptional provisions consistent with the principles referred to come to be considered.

As presidents of the Ceylon National Association and Ceylon Reform League, we pledge ourselves to accept any scheme which the Jaffna Association may put forward as long as it is not inconsistent with the various principles contained in the resolutions. We feel sure that nothing obviously unreasonable will be insisted on by the Jaffna Association. We are prepared to pledge ourselves to actively support a provision for the reservation of a seat to the Tamils in the Western Province as long as the electorate remains territorial.

We suggest that the resolution should be accepted by the Jaffna Association without any alteration and that they should leave it to us to negotiate with the Indians, Europeans and the Burghers on the subject of special representation to them.

Yours sincerely,

(Sgd.) James Peiris

President, Ceylon National Association

(Sgd.) E.J. Samarawickrama

President,

Ceylon Reform League.

Arunachalam was satisfied with the pledge given by James Peiris and Samarawickrama. He sent their letter with a note by him to Sabapathy the same day. Text of Arunachalam’s note”

Ponkar,

Horton Place,

Colombo.

7th December 1918

Hon. Mr. A. Sabapathy,

Jaffna.

Dear Sir,

Referring to your conversation with me on Thursday Afternoon, I enclose a letter from Messers James Peiris and E.J. Samarawickrama, Presidents of the Ceylon National Association and Ceylon Reform League respectively giving assurances which would satisfy your Association as the bona fide desire of the Sinhalese leaders to do all that can be done to secure as large a representation as possible to the Tamils consistent to the principles of the resolutions adopted by the committee with the concurrence of delegates from Provincial Associations.

The assurance means that you have three seats for the Northern Province and two for the Eastern Province (or more if you can get it) and that there will be one seat reserved for a Tamil Member in the Western Province on the basis of the territorial electorate, in addition to the chances of Tamils the other provinces and in the Colombo Municipality. No doubt also, the Government will nominate a Tamil to represent the Indian Tamils. Our Sinhalese friends are also willing to support the claim for a Mohammedan Member in the Western Province on the same footing, should the Mohammedans make such a claim. The conference is deliberately restricted to essential principles only, there being a conflict of opinion among the Sinhalese themselves on matters of details. Such details should be hereafter submitted by the government by the various interested parties.

I trust that nothing will stand in the way of a large number of delegates from Jaffna (including yourself and Sir A Kanagasabai) from attending the conference and making common cause with the rest of the island. I understand that the Governor is coming to Jaffna on the 14th or perhaps on the 13th by which time we hope to pass at least half the resolutions.

Yours very truly,

(Sgd.) A. Arunachalam

On the basis of the pledge James Peiris and Samarawickrama gave and Arunachalam’s note Sabapathy persuaded the members of the Jaffna Association to attend the second meeting held on December 13 and 14 December 1918. He told the members that he had been persuaded by Arunachalam that Tamils should do their part for the political advancement of the country.

The December 13 meeting convened again by the Ceylon National Association and the Ceylon Reform League to consider the reform proposals was representative. At that meeting Arunachalam and James Peiris expressed their vision of building a united Sri Lanka in which the common interests of all the communities would be accommodated. They told the audience that to achieve their common goal of self-government unity was essential. “We must ask with one voice,” Arunachalam declared.

Arunachalam suggested at that conference the need to form a common association on the lines of the Indian National Congress and it was unanimously accepted. He was authorized to work on the formation of the common organization.

Motivated by these developments Ramanathan moved a resolution in the Legislative Council on December 1918 calling for constitutional reform. The resolution requested the Government to report without further delay to the Secretary of State for the Colonies the result of its consideration about the reform of the Executive and Legislative Councils. The resolution also called for more effective popular control of Municipal and other local councils with elective chairmen and majorities of elected members, and the filling of the higher offices in the Ceylon Civil Service and other branches of the Public Service with a larger proportion of competent Ceylonese.

The motion was not pressed to a division but the Governor at the time, Sir William Manning did not in his reply commit himself, much to the dismay of the leaders of the Reform Movement. Manning pleaded that he was new to the Island having been here only for three months and that he had not had the time to study the situation in all its detail.

The inaugural sessions of the Ceylon National Congress was held on December 11, 1919 in Colombo. Arunachalam was hailed the father of the new organization and elected its first president.

The session adopted the following resolution:

The congress declares that, for the better government of the island and the happiness and contentment of the people, and as a step towards the realization of responsible government in Ceylon as an integral part of the British Empire, the constitution and administration of Ceylon should be immediately reformed in the following particulars, to wit:

That the Legislative Council should consist of about 50 members, of whom at least four-fifths should be elected on the basis of a territorial electorate, upon a wide male franchise and a restricted female franchise, and the remaining one-fifth should consist of official members and of unofficial members to represent important minorities, and the council should elect its own speaker.

The congress also demands that an Executive Council, with at least half its members Ceylonese, and that two of them should be elected members of the Legislative Council. The Congress asks for the control of the budget.

The Ceylon Daily News, successor of the ‘Ceylonese’ which was founded by Ramanathan and later sold to D.R.Wijewardene, the founder of Lake House Group of Newspapers, wrote,

(The Congress) marks the first great advance in the growth of the democratic institutions in Ceylon. The Congress takes up the positionof the only accredited mouthpiece of all classes/Those who have worked to bring it into existence have reason to be proud of its achievement.

(Next: “The First Sinhala- Tamil Rift”)

————————————————————————————

Index

Introduction

Chapter 1: The Context

Chapter 2: Origins of Racial Conflict

Chapter 3: Emergence of Racial Consciousness

Chapter 4: Birth of the Tamil State

Chapter 5: Tamils Lose Sovereignty

Chapter 6: Birth of a Unitary State

Chapter 7: Emergence of Nationalisms

Chapter 8: Growth of Nationalisms

Chapter 9: Religious Revival

Chapter 10: Parallel Growth of Nationalisms

Chapter 11: Consolidation of Nationalisms

Chapter 12: Consolidation of Nationalisms (Part 2)

Chapter 13: Clash of Nationalisms

Chapter 14: Clash between Nationalism Intensifies

Chapter 15: Tamils Demand Communal Representation

Chapter 16: The Arunachalam Factor

Chapter 17: The Arunachalam Factor (Part 2)

Chapter 18: The First Sinhala – Tamil Rift

© 1996-2021 Ilankai Tamil Sangam, USA, Inc.

Sri Lankan Tamil Struggle

Chapter 22

Dance of the turkey cock

by T. Sabaratnam, January 29, 2011

A journalist who reported the Sri Lankan ethnic crisis for over 50 years

Bandaranaike ridiculed that when radical youths of the Jaffna Youth Congress enforced the boycott they acted like the turkey cock imitating the action of the Indian youth leaders of the Indian National Congress. By using the popular allegory Bandaranaike brought out the difference between the Indian and Sri Lankan situations.

Bandaranaike’s comment

The emerging Sinhala leader S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike aptly called the boycott of the 1931 State Council election by the Jaffna Youth Congress ” the dance of the turkey cock.” In Tamil there is a famous Venba ( a Tamil poetic form) written by poetess Auvaiyar which speaks of the turkey cock (Vankoli) imitating the dance of the peacock.

Bandaranaike ridiculed that when radical youths of the Jaffna Youth Congress enforced the boycott they acted like the turkey cock imitating the action of the Indian youth leaders of the Indian National Congress. By using the popular allegory Bandaranaike brought out the difference between the Indian and Sri Lankan situations.

The Jaffna Youth Congress, which supported universal suffrage and territorial representation and advocated that Tamils should support the progressive forces among the Sinhalese, was furious with the Donoughmore recommendations. It issued a statement rejecting it and appealed to Sinhalese also to reject it. It said,

We are not prepared to accept anything less than total independence. We appeal to the Sinhalese also to reject it.

As we pointed out in the last chapter the Legislative Council accepted the Donoughmore Constitution in December 1929 and the process of setting up the State Council began with the appointment of the Delimitation Commission to draw up the constituencies to hold the elections to the State Council. The Delimitation Commission held its meetings in March 1930 in Colombo.

The Ceylon National Congress which was not happy with the rejection of the Jaffna Youth Congress decided to win over the traditional Tamil leadership to its side. It sent a delegation to meet Waithilingam Duraiswamy at his residence in Kayts and work out a seat-sharing agreement with him. The delegation persuaded Duraiswamy to accept seven seats for the Jaffna peninsula, two more than the five seats it had under the 1924 reforms. The delegation also agreed to share the 50 elected seats in the State Council in the ratio of two to one; two for the Sinhalese and one for the minorities.

Duraiswamy summoned a meeting of the All Ceylon Tamil League, in his capacity of vice president to consider the agreement he reached with the Ceylon National Congress. He moved a resolution accepting the constitution subject to the agreement that he had reached with the Ceylon National Congress. He told the meeting that his agreement would give the Tamils at least two more seats.

G.G. Ponnambalam who had just returned from Cambridge participated in that meeting and moved an amendment condemning the Donoughmore scheme as “unacceptable and injurious to the Tamils.” The amendment was carried with an overwhelming majority as the progressives led by Handy Perinbanayagam had joined hands with the group led by G.G. Ponnambalam to defeat Duraiswamy’s move to accept the Donoughmore Constitution.

Opposition to the Duraiswamy Agreement developed among the Sinhalese also. Marcus Fernando of the Unionist Association deplored the proposal to give additional seats for the Jaffna peninsula. He said that the Tamils had obtained “too much influence anyway”.

Tamils and Sinhalese presented different points of view before the Delimitation Commission. Ceylon Tamil delegations, especially the All Ceylon Tamil League led by Duraiswamy urged for additional weightage for the Tamils. He informed the Delimitation Commission about the agreement he had worked out with the Ceylon National Congress delegation and requested for two additional seats for the Jaffna peninsula.

Most of the Sinhalese leaders opposed giving the northern Tamils any additional weightage. But S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike and G.E. de Silva who led the Ceylon National Congress delegation said they were willing to “conserve the present representation” of the Tamils and indicated their willingness to give two additional seats to the Tamils. Even A.E. Goonesinghe supported the giving of additional seats but Marcus Fernando and the majority of the Sinhalese delegations opposed any such accommodation.

The Delimitation Commission refused to accede to any request for special concessions for the Tamils. It struck to the terms of reference and carved out the constituencies on the basis of one seat for 100,000 people. It allocated five seats for the Northern Province- Jaffna, Kayts, Kankesanthurai, Point Pedro and Mannar- Mullaitivu. It gave two seats for the Eastern Province- Batticaloa South and Trincomalee- Batticaloa. Thus the northern and eastern provinces were allocated only seven seats.

Tamils were dissatisfied with the recommendation of the Delimitation Commission. Several protest meetings were held in Jaffna and petitions sent to the governor. But he continued with the process of holding the election for the First State Council.

Like the traditional leaders the radical youths of the Jaffna Youth Congress too did not give up their opposition to the Donoughmore Constitution. Their opposition was completely for different reason. While the elders agitated for more seats the youths continued their opposition because the Donoughmore Constitution had failed to grant the country full freedom. They said Donoughmore Constitution was no alternative to their goal of self government. The youths did not spare the Jaffna politicians. They accused them of trying to create electorates for themselves.

The Jaffna Youth Congress conducted its agitation through its network of Youth Leagues and through Jaffna and Colombo newspapers. A survey of the Jaffna newspapers, especially the Tamil publications, reveals the virulence of the campaign conducted against the Jaffna politicians. One of the articles published in the Morning Star under the pen name ‘A Youth Leaguer’ as a comment on the evidence led by the leaders of the Jaffna Association before the Delimitation Commission accused the Jaffna politicians as “the self-interested politicians who are bent on creating electorates for themselves”. The writer of the article said the Jaffna Association “was in a moribund state” and added that its membership was composed of “the turbaned heads who represented only the aristocracy of Jaffna”.

The Jaffna Youth Congress held its sixth annual sessions in Jaffna on March 11, 1930. It was harsh on the Donoughmore Commission and on the Jaffna leaders. The sessions passed a comprehensive resolution rejecting the Donoughmore Constitution for failing to grant self government to Sri Lanka and disapproved the communalist thinking of the Jaffna leaders. It also called upon the Sinhala progressive forces to reject the Donoughmore Constitution and asked them to launch “a Gandhian type of struggle to free the country from the British yoke.”

T.C.Rajaratnam, a lawyer, in his emotional presidential address, was forthright. Inthu Sathanam, March 13, 1930 and Ceylon Daily News, March 14, 1930 quoted him as saying,

What we want is freedom for our motherland. We don’t want anything less. What we want are the rights to which we are entitled. We will accept nothing else. What we want is our birthright. We ask the British, “Give us our birthright.

The Valigaman North Youth league held its annual sessions in the specially erected Nehru Pandal at Tellipallai on April 17 and 18, 1930. In a hard-hitting presidential address T.C. Rajaratnam declared,

It is in fact the bedrock of all our political principles, and while in the name of justice and fairplay, we claim for ourselves the right of self-government, Enchained as we are, in our longing for liberty, we possess the right to break the shackles that bind us.

We have now arrived at a stage when there is a national demand for full responsible government. There are some who feel aghast at this idea –they call it preposterous – and some there are who say ‘we won’t go so far but will stop at safe distance from this goal because our rulers may consider such a demand as savouring of impudence”, while there are yet others who say “we are satisfied with small mercies and let us take a well-earned rest on these cushions the Donoughmore Commission has so thoughtfully provided us with”. Gentlemen, we have to surmount all these difficulties and a portion of our work lies here.

The March sessions of the Jaffna Youth Congress had an unexpected sequel in June that year. Jaffna students used to celebrate the King’s birthday with sports meet. Jaffna College students decided to boycott that year’s sports meet. The move was initiated by some of the younger teachers led by Bonney Kanagathungam, A. S. Kanagaratnam and C. J. Eliyathamby. To the surprise of all Jaffna College kept away.

The same evening a few youths ran to the Jaffna Clock Tower which was close to the Jaffna Central College playground where the sports meet was held, brought down the Union Jack, the British flag, and hoisted the Nandi flag, the flag of the Jaffna Kingdom.

The impulsive youth were only doing the dance of the turkey cock, imitating the dance of the Indian youth leaders. As we noted in Chapter 20 Indian youth leaders led by Jawaharlal Nehru and India’s emerging powerful youth and trade union movements had moved the Poorna Swaraj rersolution at the Madras sessions of the Indian National Congress in 1927. The young leaders who had captured the leadership of the Indian National Congress by next strengthened the independence movement by December 1928.

The next annual session of the Indian National Congress was held in Calcutta in December 1928 and the younger leaders led by Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose demanded immediate independence. Gandhi suggested that the British be given two years’ notice but a compromise to give one year was reached. The conference resolved that if India had not achieved Dominion Status by December 31, 1929 a struggle for independence should be launched.

The Labor Party won the General Elections in Britain in May 1929 and Ramsay Macdonald became Prime Minister and Wedgewood Benn the Secretary of State for India. Lord Irwin, Viceroy of India visited London to consult the new Government and announced that he would hold a Round Table Conference to discuss granting of Dominion Status for India. Gandhi and the Indian National Congress welcomed the statement.

Salt Satyagraha

Lord Irwin’s announcement raised a howl of protest in London. Conservatives and Liberals combined to condemn Irwin forcing him to retract his promise. Thus Lord Irwin was non-committal about the outcome of the Round Table Conference when Gandhi met him to seek clarification. The Indian National Congress thus decided at the December 1929 annual session to launch a campaign of civil disobedience. Jawaharlal Nehru was the president.

A model constitution for independent India drafted under the guidance of Motilal Nehru (Jawaharlal’s father) was adopted at the 1929 annual sessions at Lahoor and January 26, 1930, was observed as India’s Independence Day. Gandhi launched the famous salt satyagraha on March 12, 1930. The 400 kilometer march from his ashram in Ahmadabad to Dandi, on the coast of Gujarat, to protest against the tax on salt mobilized the entire population of India behind him. Gandhi reached the coast after the 24-day march on April 6 and collected salt symbolically defying the British rule.

Hindu Organ gave detailed coverage for the Salt March. It also carried the following story from the English journalist, Webb Miller, who witnessed one of the clashes, a classic description of the atyagraha:

Gandhi’s men advanced in complete silence before stopping about one-hundred yards before the cordon. A selected team broke away from the main group, waded through the ditch and neared the barbed-wire fence.

Receiving the signal, a large group of local police officers suddenly moved towards the advancing protestors and subjected them to a hail of blows to the head delivered from steel-covered Lathis (truncheons). None of the protesters raised so much as an arm to protect themselves against the barrage of blows. They fell to the ground like pins in a bowling alley.

From where I was standing I could hear the nauseating sound of truncheons impacting against unprotected skulls. The waiting main group moaned and drew breath sharply at each blow. Those being subjected to the onslaught fell to the ground quickly writhing unconsciously or with broken shoulders.

The main group, which had been spared until now, began to march in a quiet and determined way forwards and were met with the same fate. They advanced in a uniform manner with heads raised – without encouragement through music or battle cries and without being given the opportunity to avoid serious injury or even death.

The police attacked repeatedly and the second group was also beaten to the ground. There was no fight, no violence; the marchers simply advanced until they themselves were knocked down.

Following their action, the men in uniform, who obviously felt unprotected with all their superior equipment of violence, could think of nothing better to do than that which seems to overcome uniformed men in similar situations as a sort of “natural” impulse: If they were unable to break the skulls of all the protesters, they now set about kicking and aiming their blows at the genitals of the helpless on the ground. “For hour upon hour endless numbers of motionless, bloody bodies were carried away on stretchers.

The paper also carried several photographs of salt satyagraha. Handy Perinbanayagham told me the entire youth population in Jaffna was highly worked up. He said,

We held several marches during that period. We held special prayers in all the places of worship. We held street corner meetings. In short, we transformed the Jaffna peninsula into an emotional volcano.

The highly charged emotional atmosphere was maintained throughout 1930 and the next year. Indian political community received the Simon Commission Report issued in June 1930 with great resentment. Different political parties gave vent to their feelings in different ways.

The Congress started a Civil Disobedience Movement under Gandhi’s command. The Muslims reserved their opinion on the Simon Report declaring that the report was not final and the matters should decided after consultations with the leaders representing all communities in India.

The Indian political situation seemed deadlocked. The British government refused to contemplate any form of self-government for the people of India. This caused frustration amongst the masses, who often expressed their anger in violent clashes.

The Labor Government returned to power in Britain in 1931, and a glimmer of hope ran through Indian hearts. Labor leaders had always been sympathetic to the Indian cause. The government decided to hold a Round Table Conference in London to consider new constitutional reforms. All Indian politicians; Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Christians were summoned to London for the conference.

Gandhi immediately insisted at the conference that he alone spoke for all Indians, and that the Congress was the party of the people of India. He argued that the other parties only represented sectarian viewpoints, with little or no significant following.

The first session of the conference opened in London on November 12, 1930. All parties were present except for the Congress, whose leaders were in jail due to the Civil Disobedience Movement. Congress leaders stated that they would have nothing to do with further constitutional discussion unless the Nehru Report was enforced in its entirety as the constitution of India.

Gandhi picks grains of salt on April 6, 1930 thus breaking the British Indian laws on salt tax

Almost 89 members attended the conference, out of which 58 were chosen from various communities and interests in British India, and the rest from princely states and other political parties. The prominent among the Muslim delegates invited by the British government were Sir Aga Khan, Quaid-i-Azam, Maulana Muhammad Ali Jouhar, Sir Muhammad Shafi and Maulvi Fazl-i-Haq. Sir Taj Bahadur Sapru, Mr. Jaikar and Dr. Moonje were outstanding amongst the Hindu leaders.

The Muslim-Hindu differences overshadowed the conference as the Hindus were pushing for a powerful central government while the Muslims stood for a loose federation of completely autonomous provinces. The Muslims demanded maintenance of weightage and separate electorates, the Hindus their abolition. The Muslims claimed statutory majority in Punjab and Bengal, while Hindus resisted their imposition. In Punjab, the situation was complicated by inflated Sikh claims.

Eight subcommittees were set up to deal with the details. Those committees dealt with the federal structure, provincial constitution, franchise, Sindh, the North West Frontier Province, defense services and minorities.

The conference broke up on January 19, 1931, and what emerged from it was a general agreement to write safeguards for minorities into the constitution and a vague desire to devise a federal system for the country.

All those discussions were carried in great detail by the Jaffna papers. Elakesari which was published from Jaffna from the beginning of 1930 and Virakesari which began publishing from Colombo on August 6, 1930 carried graphic accounts of those developments. Handy Perinbanayagam told me that Tamils, especially those of the Jaffna peninsula were aware of the demands Muslim leaders placed before the Round Table Conference.

I asked him: Why were you not influenced by the demand the Muslims placed before the Round Table Conference?

Handy Perinbanayagam: Because we identified ourselves with Gandhi, Nehru, Subash Chandra Bose and the Indian National Ciongress.

Question: Looking back, don’t you feel you had erred in not identifying the Tamils with the demands of the Indian minority community?

Handy Perinbanayagam: At that time we were only moved by Indian nationalism. We thought that with the help of the Sinhala progressives we could build Sri Lankan nationalism. We simply identified ourselves with Sri Lankan nationalism.

Gandhi at First Roundtable Conference

Boycott in Action

Unmindful of the agitation in the Northern Province the governor published the Order in Council to establish the State Council on April 15, 1931 and dissolved the Legislative Council two days later and the election was fixed for the period June 13 to 30. The last day for the filing of nominations was May 4, 1931.

Tamil leaders who rejected the Donoughmore Constitution started scrambling for electorates to contest the election. Then the Jaffna Youth Congress struck.

The hard core of the Jaffna Youth Congress was highly disturbed by that scramble for electorates and decided to adopt the 1 928 Indian example of boycotting the elections. They held the Seventh Annual Sessions from April 25 to 28, 1931 at the Jaffna esplanade, presided over by S. Sivapathasuntharam, the principal of Victoria College. Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, a fire-brand orator of the left wing of the Indian National Congress, was the chief guest.

Kamaladevi was also a leader of the Indian Congress Socialist Party and one of the most colourful figures of the Indian liberation movement. A South Indian, she was the wife of the poet/playwright Harindranath Chattopadhyaya, brother of the renowned Sarojini Naidu. In 1926 she was the first woman in India to run for the Legislative Council. She was jailed for participating in Gandhi’s Salt March of 1930.

The president-elect C. Balasingham was taken in a procession from Thattatheru junction to the venue of the meeting in a carriage drawn by three white horses headed by several bands of musicians and youth clad in khadar and wearing Gandhi caps. They carried the red, green and saffron flag of the Jaffna Youth Congress which symbolized the unity of all communities living in Ceylon. The sessions witnessed the largest gathering at any sessions. The proceedings began with the singing of ‘Vande mataram’ followed by Subramaniya Bharathi’s songs on freedom.

A specially erected pandal at the Jaffna esplanade was the venue of the sessions where T.C. Rajaratnam played a pivotal role in pushing through the Boycott Resolution. That historic resolution drafted by the drafting committee headed by Handy Perinbanayagam and comprising T.C. Rajaratnam and S. Sivapathasuntharam, rejected the Donoughmore constitution and demanded Poorna Swaraj for Sri Lanka.

The resolution moved by T M Suppaiah read,

The conference holds swaraj to be the inalienable birthright of every people and calls upon the youth of the land to consecrate their lives to the achievement of their country’s freedom. And whereas the Donoughmore constitution militates against the attainment of swaraj, this congress further pledges itself to boycott the scheme.

According to Morning Star of May 3, 1931 the motion was carried by thousands of emotionally-charged youths who attended the conference chanting, “Freedom is our birthright” and “We are ready to sacrifice our lives for freedom.”

In a moving speech delivered before he moved the motion on April 25, nine days before closing of nominations for the State Council election, Suppaiah said that the youths of Jaffna had decided to reject the Donoughmore proposals because they did not confer self-government on Ceylon. He explained the boycott call was similar to that made by the Indian National Congress in 1928 which asked the Indian people to boycott the Simon Commission. “What does the Donoughmore constitution bestow on us the Ceylonese?” Suppaiah asked and answered, “Nothing. It is designed to keep us under the British bondage.”

Sivapathasuntharam who presided, said they were only following the example adopted by the Indian National Congress three years earlier. He said that Kamaladevi Chattopadhya, one of the proponents of the Indian boycott movement was with them and had advised them to adopt the Indian technique of agitation. Kamaladevi gave details about the Indian boycott decision, its implementation and outcome.

She reserved her oratorical skill for the public meeting that followed the conference over which T.C. Rajaratnam presided. Rajaratnam prefaced his speech explaining the rationale of the boycott decision. He said that was the outcome of their concern for the entire Sri Lankan people, Tamils, Sinhalese, Muslims and others. He said unlike the elders in Jaffna they never adopted a communal approach to Sri Lanka’s constitutional development. He added that the youths followed an all island approach.

Then he provided the environment for Kamaladevi’s fiery outburst. Inthu Sathanam of April 27, 1931 quoted him as saying,

We are here not to celebrate but to dedicate our lives for the cause of freedom. We are here not to talk, pass resolutions and go home and sleep. We have had many leaders who did that.

We belong to a different generation. We belong to a generation of action. We have adopted this evening a resolution to boycott the election because the Donoughmore constitution did not give Ceylon swaraj. We are not prepared to take anything less. To prove our resolve we are going to take action from now onwards. Action will be our sacred mantra.

Kamaladevi kept up that tempo. She declared that all should treat the freedom of their motherland more sacred than their lives. “It is better to die than live as slaves,” she thundered. “Boycott the election and demonstrate your will to live as free men and women,” she declared.

Handy Perinbanayagam Memorial Volume captures the reaction of the youths thus:

The youths were all worked up. They chanted ‘Boycott, boycott’ and paraded the Jaffna streets. Two of them climbed the Jaffna Clock Tower and pulled down the Union Jack, the British flag, and burnt it. In the next few days the message of boycott was spread throughout the peninsula by groups of youths who visited the villages.

Five days later, on April 30, the Youth Congress held a seminar at the Vaitheeswara Vidyalayam, Jaffna to persuade the Tamil leaders to abstain from filing their nomination papers to contest the election. They invited Vaithilingham Duraiswamy, president of the Jaffna Association to preside. The prospective candidates who were brought there declared that they would not contest the election and issued an appeal to others not to contest.

As indicated earlier, T M Suppiah who moved the boycott resolution also issued a fervent appeal to the Sinhala youth to support the boycott. The Jaffna Youth Congress which firmly believed in one independent country in which all communities would live, work and prosper together had already forged links with the Colombo Youth League formed by a group of Sinhala youths fired by the Gandhian struggle in India. The Jaffna Youth Congress expected the Colombo Youth League to back its boycott call.

The leaders of the Jaffna Youth Congress wanted to bring Nehru for the April Seventh Annual Sessions as well but Nehru who was then in Ceylon on a holiday was not free during those days. He agreed to visit Jaffna on May 8 and his visit was confirmed on May 1.The organizing group – Handy Perinbanayagam, T.C.Rajaratnam, Nagalingam, Suppaiah and Muthusamy – met and decided to show results at the massive reception scheduled to be held at the Jaffna esplanade on May 8. They also decided to bring the candidates who obeyed the boycott call to the meeting and thank them publicly for their cooperation.

Meanwhile, The Ceylon Daily News under the stewardship of D.R. Wijewardene, a strong supporter of the Jaffna Youth Congress and a virulent critic of the Donoughmore constitution, welcomed the boycott in Jaffna in its editorial written on the nomination day, May 4. It criticized the candidates in the other parts of the country for contesting the election as lacking in political principles. “One relieving feature of this soporific performance is contained in the news from Jaffna,” the editorial said.

Leftist leaders in the south supported the Jaffna boycott. Philip Gunawardene, then in London, wrote:

I longed for the day when the youth of Ceylon would take their place by the side of the young men and women of China, of India, of Indonesia, of Korea and even of the Philippine Islands in the great struggles of a creative revolution of all the mighty forces of old age, social reaction and imperialist repression. During the last few years the Jaffna Students’ Congress was the only organization in Ceylon that has been displaying political intelligence … Jaffna has given the lead, They have forced their leaders to sound the bugle call for the great struggle for freedom- for immediate and complete independence from imperialist Britain. Will the Sinhalese who always display supreme courage, understand and fall in line? A tremendous struggle faces us. Boycott of the election was only a signal. It is the duty of every Sinhalese to prepare the masses for a great struggle ahead.

The boycott was successful only in the Jaffna peninsula and on the nomination day, May 4, no nomination paper was filed for the four constituencies in the peninsula. The Jaffna Youth Congress volunteers ensured that no one slipped to the Jaffna kachcheri on the sly and filed his papers. They blocked all the roads leading to the kachcheri including the adjoining lanes. The Jaffna Government Agent, the returning officer, thus announced that no election could be held in the electorates of Jaffna, Kayts, Point Pedro and Kankesanthurai.

Tamil candidates filed nomination papers in the Mannar – Mullaitivu electorate in the Northern Province and two electorates in the Eastern Province. In the rest of the country the boycott was ignored. And in the 46 electorates in which nomination papers were filed nine were uncontested. The members elected uncontested were: D.B. Jayatileka, D.S.Senanayake, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, Peri Sundaram, D.H. Kotalawela, J.C. Ratwatta, A.M.Molamure, J.H. Meedeniya and J.C.Rambupota.

The Jaffna Youth Congress was elated that the boycott was successful in the Jaffna peninsula. Its members collected a massive crowd on May 8 to listen to Nehru. The Ceylon Daily News quoting the police said that was the biggest meeting held in Jaffna and estimated the crowd to be over 10,000. Most of the Tamil leaders who boycotted the election were honoured and allowed to address the crowd.

Nehru, according to the newspaper reports, delivered a sober and thoughtful speech. He welcomed the success of the boycott movement but gave a guarded warning. He said that the organizers should endeavour to make it effective throughout the country. Then only that would be total and fruitful, he said.

Nehru had made reference to his Jaffna visit in his book Glimpses of World history. He did not mention the public meeting but he recorded an incident he remembered. The relevant extract:

The little incident lingers in my memory; it was near Jaffna, I think. The teachers and boys of a school stopped our car and said a few words of greeting. The ardent, eager faces of the boys stood out, and then one of them came to me shook hands with me, and without questioning or argument said, “I will not falter.” That bright young face with shining eyes, full of determination, is imprinted in my mind. I do not know who he was; I have lost trace of him. But somehow I have the conviction that he will remain true to his word and will not falter when he finds life’s difficulties.

Inthu Sathanam has reference to that incident. It happened in Kokuvil when he was taken around Jaffna suburbs by T.C. Rajaratnam in his car. Rajaratnam was looking after Nehru. He had met Nehru a week earlier at Dehiowitta when he attended a youth conference organized by the left group headed by Dr. S.A. Wickramasinghe. Rajaratnam attended that conference as the leader of a small delegation of the Jaffna Youth Congress. He garlanded Nehru on behalf of the Jaffna Youth Congress.

Nehru says in his book that he came to Ceylon with his wife Kamala and daughter Indira on the advice of his doctors to take rest. He says that he had to attend several meetings. That was Nehru’s first visit to Ceylon.

The Tamil leaders made a joint call from that meeting urging the Sinhalese to join the boycott. Duraiswamy read a resolution which said that though they had filed the nominations and some had been declared elected uncontested they should join the boycott by declining to participate in the proceedings of the State Council. The resolution said,

… the Jaffna Youth Congress calls upon the people of Ceylon to boycott the State Council and to work for the immediate attainment of Swaraj.

The Colombo Youth League responded to this call with a resolution of support for the boycott. It was passed at the instance of T.B. Jayah, Valentine and Aelian Perera. The appeal for boycott sent to the nine members who were elected uncontested was ignored. One of the candidates contesting the election, Francis de Zoysa, sent a telegram to Duraiswamy asking him and other Jaffna leaders to send them a signed joint statement declaring their support for the enactment of a new constitution “granting Responsible Government based on adult suffrage without any form of communal representation.”

Francis de Zoysa’s request showed the unwillingness of the Sinhalese leadership to forgo the advance they had gained: territorial representation and universal suffrage which placed the Sinhalese at a position of advantage. The Sinhalese leaders, quite legitimately, feared that the Jaffna Tamil leadership would reopen their demands of communal representation and limited suffrage whenever they got an opportunity.

The Jaffna Youth Congress, in a booklet published in 1939 which reviewed the reasons for the failure of the boycott said,

The Sinhalese were afraid to join the boycott and let slip the opportunity of once and for all abolishing communal representation. They thought, if they boycotted communal representation would not be abolished.

Opposition to the boycott surfaced in Jaffna soon after the nomination was over. Anti-boycotters issued a leaflet calling for a meeting on June 12, the day before the election. The leaflet warned that by keeping out of the election the Jaffna Tamils would be the ultimate losers. The Jaffna Youth Congress activists broke up that meeting.

Next: Tamils Beg for By-election

Index

Introduction

Chapter 1: The Context

Chapter 2: Origins of Racial Conflict

Chapter 3: Emergence of Racial Consciousness

Chapter 4: Birth of the Tamil State

Chapter 5: Tamils Lose Sovereignty

Chapter 6: Birth of a Unitary State

Chapter 7: Emergence of Nationalisms

Chapter 8: Growth of Nationalisms

Chapter 9: Religious Revival

Chapter 10: Parallel Growth of Nationalisms

Chapter 11: Consolidation of Nationalisms

Chapter 12: Consolidation of Nationalisms (Part 2)

Chapter 13: Clash of Nationalisms

Chapter 14: Clash between Nationalism Intensifies

Chapter 15: Tamils Demand Communal Representation

Chapter 16: The Arunachalam Factor

Chapter 17: The Arunachalam Factor (Part 2)

Chapter 18: The First Sinhala – Tamil Rift

Chapter 19: The Birth and Death of the Jaffna Youth Congress

Chapter 20: The Birth and Death of the Jaffna Youth Congress (Part 2)

Chapter 21: Tamils Take the Wrong Road

Chapter 22: The Dance of the Turkey Cock

Chapter 23: Tamils Beg for By-election

© 1996-2018 Ilankai Tamil Sangam, USA, Inc.

http://sangam.org/2011/02/Tamil_Struggle_22.php

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.