Thimpu Talks 1985

file:///C:/Users/Thang/Folder%20D/Old%20F%20(E)%20on%20Owner/thanga3/Mahinda.pdf

Pirapaharan, Chapter 35

by T. Sabaratnam

(Volume 2)

Thimpu Talks – the First Round

On 3 July 1985 the ENLF leaders – Pirapaharan, Sri Sabaratnam, Pathmanabha and Balakumar – and their assistants were flown in an airforce plane to Delhi and were accommodated in the five-star Hotel Ashok.

RAW officials accompanied them and kept constant vigil over them. RAW, Defence and Foreign Affairs officials gave lengthy briefings to the militant leaders. They concentrated on persuading the militant leaders not to impose conditions for participating in the talks. They said imposing conditions would help Jayewardene to wriggle out of the talks.

RAW officials accompanied them and kept constant vigil over them. RAW, Defence and Foreign Affairs officials gave lengthy briefings to the militant leaders. They concentrated on persuading the militant leaders not to impose conditions for participating in the talks. They said imposing conditions would help Jayewardene to wriggle out of the talks.

Militant leaders told the officials, Jayewardene was only trying to buy time and ceasefire and talks suited him. They also told the officials that, whether they imposed conditions or not, Jayewardene was going to wriggle out of the talks when he was confident that the army could crush the armed resistance. They told them Lalith Athulathmudali had intensified the militarization program. He had stepped up recruitment, he was setting up an auxiliary force called the Home Guards and was arming Sinhala civilians. He was also buying weapons.

The officials told the militant leaders they, too, were aware of all those matters. “We too have our agenda. Let Jayewardene wriggle out. We will see,” they said. They gave the assurance that India would look after the interest of the Sri Lankan Tamils. “Go to Thimpu. We will look after you,” was their refrain.

The officials kept repeating the argument that the Thimpu talks would win for the Tamil militants official Indian and Sri Lankan recognition as freedom fighters and they should not allow that chance to slip. They pointed out that Romesh Bhandari had spent a lot of energy to persuade Jayewardene to agree to talk to them. Jayewardene had maintained that the government had decided not to talk to terrorists, but Bhandari had pressurized him to change his policy.

Bhandari cited to Jayewardene the talks Rajiv Gandhi was having at that time with Sikh leader Harchand Singh Longowal as an example for talking to rebels. And Rajiv Gandhi sent Jayewardene a message through his Deputy Foreign Minister Khursheed Alam Khan about the benefit of settling ethnic rebellions through talking with the rebels immediately after he signed the agreement with Longowal.

Rajiv Gandhi who won international admiration for solving the Sikh dispute, wanted to add another feather to his cap by getting Jayewardene and Tamil militants to talk. Solving the Sikh militancy won him national fame. Solving the Sri Lankan discord would win him regional renown. As Mervyn de Silva summed up in his News Background of the 1 August 1985 issue of the Lanka Guardian Rajiv Gandhi could not be seen as failing in his “first essay in regional conflict- management or optimistically conflict-resolution.”

RAW officials told the militant leaders their insistence on imposing conditions was causing embarrassment to India. Bhandari had already given Jayewardene an assurance that he would bring the militant groups to the negotiating table and failure to do so would damage India’s image as a regional power. For India, making the militant groups attend the Thimpu talks had become a prestige issue, they said. “You must go to Thimpu,” they insisted.

Chandrasekaran went further. He told the militant leaders, “We are not asking you to give up your struggle. But you must go to Thimpu.”

The apex of the ‘briefing’ effort was the meeting Saxena had with ENLF leaders at his office in the RAW headquarters. Saxena, tall and fair, a man with an imposing personality and sparkling eyes, told the militant leaders in his commanding voice that they should cooperate with India. He told them India had looked after them during Indira Gandhi’s time. It had provided them with protective sanctuary. The new administration had embarked on a new policy of creating a zone of peace in South Asia. Talks with Sri Lanka had been planned in that context.

Saxena said that Bhandari had spent considerable energy to pressurize Jayewardene to agree to talk to the militant groups. That was a major victory for the militant groups. Imposing conditions would provide Jayewardene a chance to wriggle out of his commitment to send a delegation to Thimpu. He told them their cooperation with India’s effort was expected.

ENLF Strategy

Saxena concluded the briefing with the stern warning, “The dialogue will be unconditional. If you refuse to attend neither Indian soil nor territorial waters will be made available to you. All of you seriously reflect on what I have said and come out with a positive decision tomorrow.”

ENLF leaders considered Saxena’s appeal for cooperation and his threat on their return to the hotel. Pirapaharan, according to Balasingham, was forthright. He told the others, “We cannot antagonize India at this juncture. We should go along with India. We should go to Thimpu without conditions. We should not permit Jayewardene to drive a wedge between India and us. Rajiv Gandhi and Bhandari are believing Jayewardene. We should break that trust.”

But Pirapaharan was firm that going to Thimpu would not involve sacrificing the interests of the Sri Lankan people. He told the other ENLF leaders, “We will go to Thimpu. We will go there without conditions. After going there we will insist on the rights of the Tamil people.”

At that late night meeting, ENLF leaders worked out their strategy. The strategy involved two aspects. The first was to break Rajiv Gandhi’s growing trust in Jayewardene. They decided to do it by showing themselves as ‘good boys’ and Jayewardene as ‘a trickster.’ For this purpose they would adhere strictly to the ceasefire and highlight the ceasefire violations of the police and the army,

ENLF leaders gave strict instructions to their fighters to completely observe the ceasefire. A leaflet, signed by the ENLF leaders, was distributed throughout the northeast explaining the importance of observing the ceasefire very strictly. Copies of that leaflet was given to RAW.

The second portion of the strategy was to show to India that Jayewardene was not prepared to give the Tamils a fair and just solution. He was not prepared to consider the very basics of the solution to the Tamil problem – that Tamils constitute a nation, that they live in an identifiable homeland, that they enjoy the right to self-determination and that they enjoy the right of citizenship.

ENLF leaders agreed to attend the Thimpu talks without conditions. Balasingham conveyed that decision to Chandrasekaran immediately. Indian officials were pleased. When the reporters asked what made them to decide to go to Thimpu, Balakumar replied, “We want to listen to what Sri Lanka has to offer as a solution.”

Sri Lanka announced a delegation of lawyers and foreign ministry officials headed by H. W. Jayewardene as its representatives. ENLF leaders pointed out that to the RAW officials. Balasingham told Chandrasekaran, “We told you that Jayewardene is going to buy time. Now, look at the delegation he is sending. A team of lawyers who cannot take any political decision. What can we expect those people to do? They will only argue their brief. So there cannot be any serious discussions.”

India took up the status of the delegation through Dixit with Jayewardene. Dixit conveyed Delhi’s concern to Jayewardene. He told Jayewardene his failure to appoint a senior minister or someone with constitutional status had diminished the purpose of the talks.

Jayewardene, as usual, bluffed his way through. He gave four reasons in support of his decision to send a group of lawyers headed by his younger brother, Hector Jayewardene. He said he was sending his younger brother because he was his advisor and he held him in high trust. He said he was also a trained constitutional lawyer of high repute. He had held consultations with the Indian Attorney General and together with him had formulated mechanisms to devolve power to regional structures within Sri Lanka’s unitary constitution, and he was sending him as his special envoy which gave him special status and credentials.

Foreign Affairs Ministry officials conveyed Jayewardene’s answer to Balasingham. ENLF leaders considered Jayewardene’s reply and decided to send a second level delegation. Then the leaders spent their time going to cinema and sightseeing in New Delhi.

Pirapaharan went with Balakumar, Varatharaja Perumal and Shanthan to Chanakya Theatre to see an English film. The story revolved around a young couple and Balakumar, the unmarried man among them, was highly embarrassed.

Pathmanabha

Indians took the militant leaders to Raj Ghat on the banks of the Yamuna to pay respect to Mahatma Gandhi. Pirapaharan whispered to Pathmanabha, “Why do you think the Indians brought us here? They want us to take to non-violence.” Balakumar who was standing behind them asked, “What are you whispering to each other?” Pirapaharan smiled.

Indians took the militant leaders to Raj Ghat on the banks of the Yamuna to pay respect to Mahatma Gandhi. Pirapaharan whispered to Pathmanabha, “Why do you think the Indians brought us here? They want us to take to non-violence.” Balakumar who was standing behind them asked, “What are you whispering to each other?” Pirapaharan smiled.

Jaffna Erupts

In Jaffna protests erupted. Youths orchestrated their anger against the militant leaders for agreeing to talk to the Jayewardene government without conditions. They exhibited their anger against India for frog-marching the militant leaders to New Delhi. They organized protest marches, public meetings and street plays. The graffiti on the walls and roads, the streamers hung across the streets and buildings, the placards displayed at the rallies and slogans shouted in the protest marches backed the demand for a separate state of Tamil Eelam. “We want Tamil Eelam,” was the united shout.

Condemnation of the army and the Jayewardene government and criticism of the Indian policy of imposing its will on the Sri Lankan Tamil people were the other sentiments orchestrated by the screaming protesters. Speakers at the public meetings highlighted two messages – Tamils do not trust Jayewardene and Tamils rejected the TULF because they negotiated with Jayewardene.

Jaffna University and school students took the lead in organizing the rallies. Protests started on 3 July, the day militant leaders were flown to Delhi. On that day, several marches were held all over the Jaffna peninsula. At Tellipalai an angry mob dragged the effigy of Amirthalingam along the road with boys dressed as mourners wailing, “You committed political suicide by talking to JR (Jayewardene), but still you have not realized your folly.”

A Jaffna University drama group staged a street play named Mayaman (The Illusive Deer). The play adapted the story from the Ramayana where Rawana uses an illusive deer to snare Rama and Laxmana before taking Sita captive. The play presented the talks as an illusion created to make Tamils slaves of the Sinhalese. India was depicted as forcing the militant groups to walk into that hidden trap. India walks towards the trap and the five militant groups – four of the ENLF and the PLOTE – were whipped to follow. India walks and they walk behind. India stops and they stop. India tells them to jump and they jump.

When the militants step out of the line, India uses the whip and makes them fall in line. The 35-minute humourous skit was so popular it was performed at least 125 times across the peninsula over that week.

On 8 July 1985, the first day of the Thimpu talks, the Jaffna peninsula was crippled with a general strike. University and school students boycotted classes, shops pulled down the shutters, vehicles kept off the roads and people stayed indoors. Banners proclaimed, “We want Eelam”, “Down with ceasefire”, “We don’t want talks.” One banner pointedly asked India, “Why are you taking the Tigers to Thimpu. To eat grass?”

The militant groups seized these protests as an opportunity to mobilize the people and to tell India, “Look! You are forcing us to talk to the Jayewardene government. The people are against it.” But Indian officials were not in a mood to listen. To them talks were important. Talks would improve India’s status as a regional power.

Talks Begin

Talks began on 8 July 1985. The 10-member Sri Lankan delegation headed by Hector Jayewardene and the 13-member Tamil delegation were taken to Thimpu under heavy security and were housed in different hotels. Tight security was imposed throughout Thimpu. Journalists and tourists were forbidden from entering the Bhutanese capital. Two Indian journalists, India Today’s Chennai correspondent S. H. Venkatramani and his photographer, who sneaked into the city as tourists were unceremoniously woken up in the middle of the night and politely told to leave the country at dawn.

At the hotel, the Tamil delegates were kept virtual hostages. They were not allowed to meet outsiders. They were also not allowed to make telephone calls. But they were provided with a ‘hot line’ to a secret destination in Kodampakkam in Chennai. The delegates were told they were free to consult their leaders who had returned to Chennai on that special line. Chandrasekaran and another senior RAW official facilitated the talks. Chandrasekaran looked after the Tamil side and the other official the government side.

The militant leaders returned to Chennai after the delegations left for Thimpu. Pirapaharan left for the LTTE camp in Salem leaving Balasingham to guide the Thimpu talks. Pathmanabha, Balakumar and Sri Sabaratnam stayed in Chennai.

Pirapaharan knew that the Thimpu talks would collapse. And he has also decided, according to Venkatramani, by that time Indian and Tamil interests were on a collision course, and had prepared himself mentally to return to the northeast and continue the Tamil freedom struggle.

Pirapaharan went to Salem to plan the next military action and to train his fighters for that task. As he had told the other ENLF leaders earlier, his next move was to place his fighters around the police stations and army camps and confine the policemen and the soldiers to their stations and camps. He told Kittu that his next assignment was to prevent the forces from coming out.

The delegates briefed their leaders in Chennai about the progress of the talks at Thimpu and received their guidance. At Chennai and at Thimpu ENLF leaders and delegations acted as one group. They made collective decisions. In Chennai Balasingham acted as the coordinator and at Thimpu Thilakar performed that function. At Thimpu the ENLF delegates coordinated with the PLOTE and TULF delegations.

Dharmalingam Siddarthan, currently leader of PLOTE, told me that the Thimpu talks were the only occasion the Tamil leadership acted in unison, which surprised the Sri Lankan delegation. “They expected us to quarrel among us and speak at cross purposes. We planned every move very carefully. We even decided the persons who should speak and the matter he should present in his address,” Siddarthan said.

At Chennai, Balasingham was responsible for guiding the delegations. He knew RAW was listening to all the conversations. So he used Jaffna colloquial language, which kept RAW’s Indian Tamil officers confused.

Besides its leader Hector Jayewardene, the Sri Lankan delegation comprised lawyers H. L. de Silva, L.C. Seneviratne, Mark Fernando and S.L. Gunasekera. Others were foreign ministry officials. HL de Silva

HL de Silva

The Tamil delegation consisted of Amirthalingam, Sivasithamparam and Sampanthan of the TULF, Lawrence Thilagar and Sivakumaran (Anton) of the LTTE; A. Varadarajah Perumal and Ketheeswaran of the EPRLF; Charles Antony Das and Mohan of the TELO; Shankar Rajee and E.Ratnasabapathy of the EROS and Vasudeva and Siddharthan of the PLOTE.

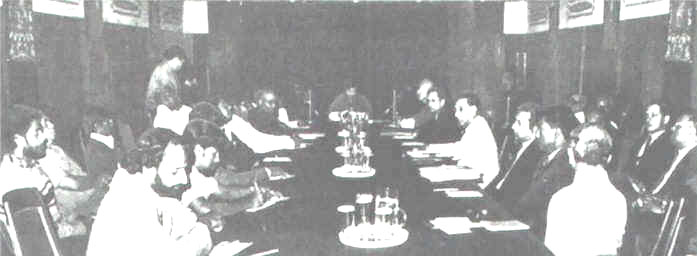

Bhutan, being the host, its Foreign Minister, Lyonpo Dawa Tsering, formally inaugurated the meeting in the exquisitely designed Banquet Hall of the Royal Palace with gleaming chandeliers. Dawa stressed the importance of working out political disputes between estranged groups of citizens of a country and wished the exploration for peace success. Hector Jayewardene thanked India for arranging the meeting and Bhutan for hosting it and for its hospitality. Charles of TELO proposed the vote of thanks on behalf of the Tamil delegations, thus giving an indication of the unity that was exhibited by the Tamil side. The first day of the historic Thimpu Talks ended with a glittering reception Bhutan Foreign Minister accorded to the participants.

On the second day, 9 July, the two groups sat facing each other across the long and ornate table. Amirthalingam opened the discussions on behalf of the Tamil side. As decided by the delegates in the morning and in keeping with the strategy planned by their leaders, the Tamil side raised three matters. Firstly, they questioned the seriousness with which the Sri Lankan government had approached the talks. They pointed out that their assessment that the government was trying to buy time through the talks to strengthen the army was borne out by the fact that the government had sent a group of lawyers and officials with no decision-taking power.

Amirthalingam remarked caustically, “This strategy is nothing new. The government dragged the talks the whole of last year and it wants to do the same this year.”

Hector Jayewardene answered the charge. He declared he had come with the full authority of the Sri Lankan government to conduct serious businesslike negotiations to “resolve the ethnic dispute once and for all.” And he announced that, if the talks made progress, President Jayewardene was prepared to come to Thimpu to seal an accord.

Tamil delegates also objected to the presence of Sri Lankan intelligence personnel in the government delegation.

Hector Jayewardene, in turn, questioned the legitimacy of the representatives of the Tamil militant organizations and challenged the claim that they are the representatives of the Tamil people. “Whom are you representing? You are not representing the Tamil people?” he asked. He said the militant organizations were representing only themselves. They did not represent the Tamil people either in the northeast or in the rest of Sri Lanka. They did not represent the Muslims, he argued. He added that the Sri Lankan delegation represented the Tamils, too.

This led to an acrimonious debate. The Tamil side said that, if the Sri Lankan delegation claimed that it represented the Tamils also, then why was it talking to them. “You can talk among yourselves and settle the dispute, ” one of the Tamil delegates quipped. The Tamil side said they were not prepared to talk to the government delegation if it refused to accept that they represented the Tamil people.

This led to an acrimonious debate. The Tamil side said that, if the Sri Lankan delegation claimed that it represented the Tamils also, then why was it talking to them. “You can talk among yourselves and settle the dispute, ” one of the Tamil delegates quipped. The Tamil side said they were not prepared to talk to the government delegation if it refused to accept that they represented the Tamil people.

The Tamil side asked for a short recess and announced they would talk only if they were accepted as the representatives of the Tamil people. During the recess the Tamil side met separately and discussed their strategy. They felt that the government side was trying to drive a wedge between the TULF and the militant groups. They decided unanimously to foil that attempt. They decided to present all their written statements as statements of the “Delegation of the Tamil people.’

After the recess, Hector Jayewardene made a statement clarifying the government position. He said both sides were primarily interested in finding a solution to the ethnic problem and the holding of talks was itself a recognition of the fact that at the meeting there was sufficient representation of the Tamils to enable the search for a final solution.

The Tamil side then raised the second matter, the issue of ceasefire violations. They charged that Colombo had failed to honour the terms of the ceasefire. They pointed out the sections in the Indian ceasefire proposals the government had failed to implement. They pinpointed the sections dealing with the suspension of curfews and raids. The armed forces are continuing with night curfews and arrests, they charged. They pointed out that they had stuck to the terms of the agreement and had suspended all forms of attacks on the armed forces and the civilians.

The Tamil side submitted its first joint statement signed by the heads of the six delegations. The following is the text of the joint statement:

The Tamil side submitted its first joint statement signed by the heads of the six delegations. The following is the text of the joint statement:

Statement made by Joint Front of Tamil Liberation Organisations on 9.7.85

concerning cease-fire violations by the Sri Lankan Government

In appreciation of the personal initiative taken by the Prime Minister of India, Mr. Rajiv Gandhi, and the good offices provided by the Government of India, we have suspended all military operations in order to create a congenial atmosphere and conditions of normalcy in the Tamil areas as a prelude to a negotiated settlement. The Sri Lankan Government which had similarly pledged to implement a series of reciprocal measures has failed to do so. Instead, the Sri Lankan Armed Forces continue to engage in hostile activities and other acts of provocation against the Tamil civilians. We give below instances of violations of cease-fire committed by the Sri Lankan Security Forces:

1) Harassment of fishermen: Though the Sri Lankan Government formally declared a partial suspension of the sea surveillance zone, the Sri Lankan Navy personnel continue harassing, intimidating and assaulting the Tamil fisherman. Fishermen from Valvettithurai, Thondamannaru, Point Pedro, Thalayadi and the coastal area of Mullaithivu who ventured into the sea were beaten up with barbed wire, their boats fired at and their ‘catch stolen.’

2) The killing and harassment of civilians: The weeks immediately following the declaration of cease-fire have witnessed the killing of several youths, some of whom were unarmed cadres of the Liberation Organisations. These killings have taken place without any provocation. To mention a few such instances during that period between 18th June to 8th July are:

(i) In a village called Kokkudayar in Mannar, the army personnel shot dead 4 young men and burnt their bodies.

(ii) At Munnakam, army personnel opened fire on two young men riding a motor-bike. One youth was killed and the other escaped with shotgun injuries. The army burnt the dead body to erase any sign of identity.

(iii) At Muthur, two young men were shot dead and their bodies cremated at the Muthur army camp.

(iv) At Mandur, 4 youths were arrested by the security forces.

(v) At Thanthamalai in Batticaloa, a group of farmers travelling in a tractor were severely attacked and the tractor destroyed. This attack was led by Sub Inspector Piyasena.

(vi) In Karadiyan Aru, 50 Tamil houses were set on fire and systematic destruction is continuing and three further villages have been added since 18th June 1985.

(vii) At Kiran (Batticaloa), the security forces, failing to apprehend two youths, engaged in indiscriminate assault of civilians.

(viii) Police commandos stationed in Elephant Pass, while on their way to Kilinochchi Police station engaged themselves in random firing at civilians in order to terrorise the people.

(ix) At Kumburumoolai junction at Batticaloa, a new building which was to house the Government Press was taken over by the army and fortified. 16 truck loads of civilians were forcibly taken by the army to the camp for this purpose.

Reports are continuing to reach us on the harassment and killings of civilians and unarmed cadres.

3) Tension in the Northern and Eastern Province: Though there is some element of relaxation of military repression in the Jaffna peninsula, the other parts of the Northern and Eastern Provinces are held under tight military surveillance and harassment of Tamil civilians continues unabated. Patrolling, road-blocks, search, arrest and other operations are being continued by the Sri Lankan armed forces in a deliberate campaign of instilling tension and terror among the Tamil civilian population in the Eastern Province. This is occurring despite the announcement to lift the prohibited zone.

4) Continuing tension in the Plantation areas: A virtual state of siege continues to prevail in the plantation areas involving restrictions on the movements of the plantation Tamils in and out of these areas. These restrictions also apply to persons intending to visit these estates thereby totally cutting off contacts with the rest of the country. Furthermore, the Tamil youths in these areas who have been detained have not been released.

In addition to the above instances of the flagrant violation of the cease-fire by the armed forces, the Sri Lankan Government has further failed to adhere to the cease-fire agreement through the non-release of political detainees and the continued enforcement of curfew in the Tamil areas.

In view of the mutual commitment of the Sri Lankan Government and the Tamil Liberation Organisations to the success of the on-going peace progress, we demand that immediate steps be taken by the Sri Lankan Government to adhere to the terms of the cease-fire agreement.

The Tamil side also pointed out that intrusion of men and material from outside was continuing. The army had bought four helicopter gunships from Pakistan and the navy had purchased 18 gunboats from China, they pointed out.

Hector Jayewardene promised to look into question of curfews and the release of detainees and give his response in the afternoon. He contacted his brother, President Jayewardene, on the hot line during lunch and announced in the afternoon the government would lift the curfew in the northern and eastern provinces the next day and would release 643 of the 1,197 of the detainees within the next two days.

Next

Chapter 35 Continued, Thimpu Talks

Posted February 18, 2005

Thimpu Fiasco

by Shamindra FerdinandoNew Delhi airport June 3, 1985: President JRJ leaving India after three days of consultations. JRJ is flanked by Premier Rajiv Gandhi and President Zail Singh

by Shamindra FerdinandoNew Delhi airport June 3, 1985: President JRJ leaving India after three days of consultations. JRJ is flanked by Premier Rajiv Gandhi and President Zail SinghLess than 24 hours after President JRJ’s brother left for New Delhi to work out modalities for a ceasefire, troops raided an LTTE hideout in the Mannar district, where they killed at least 18 terrorists and recovered a large quantity of arms and ammunition. Having visited troops involved in the operation, the then National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali declared that those killed had been involved in the May 14, 1985 raid on Anuradhapura. Minister Athulathmudali said that the killers of innocent Buddhist pilgrims had been punished.Having rejected the then President J. R. Jayewardene’s request for joint naval patrols to stop gun running across the Indo-Lanka maritime boundary, Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi invited the Sri Lankan leader for talks in New Delhi in early June 1985.

The then Indian External Affairs Ministry Secretary, Romesh Bhandari played a key role in arranging the visit in the wake of External Affairs Minister Khursheed Alam Khan rejecting President JRJ’s appeal. Under heavy pressure from Tamil Nadu, Minister Khan told the Lok Sabha on April 29, 1985 that Sri Lanka’s proposal was not acceptable.

The then Indian External Affairs Ministry Secretary, Romesh Bhandari played a key role in arranging the visit in the wake of External Affairs Minister Khursheed Alam Khan rejecting President JRJ’s appeal. Under heavy pressure from Tamil Nadu, Minister Khan told the Lok Sabha on April 29, 1985 that Sri Lanka’s proposal was not acceptable.

The appeal was made by the then National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali on behalf of President JRJ during a visit to New Delhi.

President JRJ waves at Indian leaders. National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali, wife, Srimani and first lady Elena

President JRJ waves at Indian leaders. National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali, wife, Srimani and first lady Elena

Although an influential section of the government and the military top brass felt that India was bent on destabilising Sri Lanka, President JRJ had no option but to go ahead with his first visit to New Delhi since Rajiv Gandhi assumed power following his mother’s killing.

Minister Athulathmudali and his wife Srimani accompanied President JRJ and First Lady Elena Jayawardena.

LTTE storms A’pura

Although JRJ and Rajiv agreed to take meaningful measures to end violence, including a halt to illegitimate boat movements between northern Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu, the Palk Straits remained the main supply route for terrorists fighting in the Jaffna peninsula. In spite of Gandhi’s assurances, the destabilisation project continued with terrorists stepping up attacks. In the run-up to JRJ’s June visit, the LTTE massacred nearly 150 men, women and children at Sri Maha Bodhi in Anuradhapura on May 14, 1985.

June 2, 1985 New Delhi: President JRJ with Indian President Zail Singh

The unprecedented raid on Anuradhapura followed massacres of over 60 Sinhalese at Dollar and Kent farms in the Weli Oya region on Nov. 30, 1984. The Anuradhapura massacre was meant to provoke a backlash. The LTTE and its New Delhi-based masters believed a fresh wave of attacks on Tamil civilians could embarrass Sri Lanka ahead of efforts to bring the warring parties to the negotiating table.

The LTTE however, alleged that the Anuradhapura raid had been prompted by the army massacring civilians at Prabhakaran’s birthplace Valvettiturai on May 12, 1985. The army was accused of killing 70 civilians after having rounded them up and forced into them enter a library in that township.

Obviously, an influential section within the Indian government acted against the position taken by Premier Gandhi. Those opposed to a change in India’s policy towards the JRJ government worked overtime to undermine the peace efforts. The Tamil Nadu factor greatly influenced the Central Government which needed TN backing for its political survival. On the other hand, those who had been spearheading the destabilisation project in Sri Lanka didn’t want to ditch Tamil groups fighting in Jaffna on India’s behalf.

The RAW had direct dealings with the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) as well as terrorist groups. Gradually, the TULF lost its appeal as relations between RAW and terrorist groups rapidly grew, much to the discomfort of those trying to bring about an amicable settlement.

Having met Premier Gandhi on June 2 and 3, 1985, President JRJ didn’t mince his words when he told The Far Eastern Economic Review that he expected India to stop sponsoring terrorism. President JRJ declared that he would expect his ministers to support the latest peace initiative or face the consequences. JRJ emphasized that he wouldn’t hesitate to dismiss any minister opposed to the New Delhi initiative. The Far Eastern Economic Review quoted President JRJ as having said: “We told them (Indian PM and officials) that statements from terrorists made in India are meant to destabilise Sri Lanka. We even showed them films of terrorist training camps in Tamil Nadu. They said that they will look into it.”

JRJ assured that his forces would comply with the peace initiative. At the conclusion of talks on June 3, President JRJ flew to Bangladesh with Premier Gandhi to visit an area devastated by a cyclone before returning to the country on the same day.

In a joint communiqué issued in New Delhi, the two leaders agreed that all forms of violence should stop and immediate steps should be taken to defuse the situation and create a climate for progress towards a political solution.

Addressing the UNP parliamentary group the following day, a confident President quoted President Zail Singh and Premier Gandhi as having told him that they wouldn’t support terrorist acts conducted against Sri Lanka from Indian territory. He was mistaken!

Enter JRJ’s brother

Due to the sensitive nature of highlevel consultations between India and Sri Lanka in the run-up to President JRJ’s visit to New Delhi, the beleaguered UNP leader feared to entrust senior ministers or officials with the responsibility of speaking on his behalf.

Although Minister Athulathmudali had made representations to Premier Gandhi in New Delhi a few months ago, he was not chosen for the new assignment.

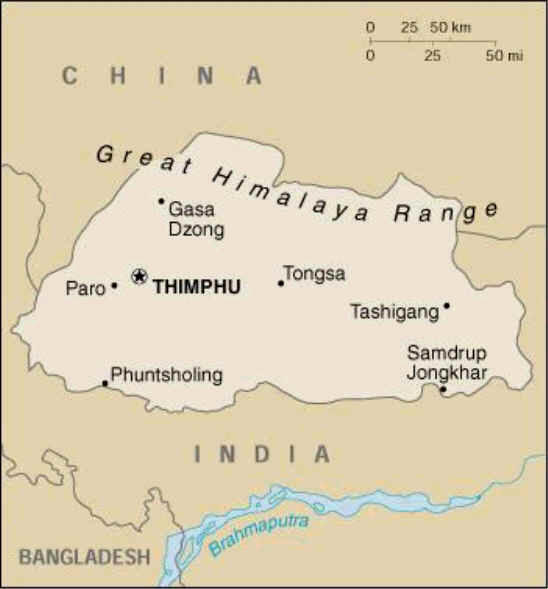

Instead, President JRJ placed his brother, H. W. Jayewardena, QC in charge of the government delegation for the first formal tripartite negotiations involving India, Sri Lanka and representatives of Tamil speaking people of Sri Lankan origin living in Sri Lanka and overseas. The capital of Bhutan, Thimpu was agreed upon as a neutral venue for talks scheduled to begin in early July 1985. Thimpu was India’s choice. Although Sri Lanka resented having being compelled to meet the TULF and terrorists away from the country, the government had no option but to go along with the Indian plan.

Prior to the Thimpu talks, QC Jayewardene visited New Delhi, where he had talks with Prime Minister Gandhi and Indian Attorney General K. Parasaran. The President’s younger brother was accompanied by Legal Draftsman Nalin Abeysekera.

A foolish move

In view of the Thimpu talks, the government suspended military operations in the northern and eastern districts. The suspension of operations came into effect during the then Colonel Gerry De Silva’s tenure as the Northern Commander from May to November 1985. At India’s behest, the government suspended operations on June 18, 1985 to facilitate the Thimpu talks scheduled to begin in early July, 1985. The ceasefire imposed severe restrictions on the police and the military, whereas Tamil groups could operate freely. Terrorists stepped up their presence in the peninsula in the wake of the first formal ceasefire. India turned a blind eye to a rapid terrorist build-up in the Jaffna peninsula. India failed to realise that the LTTE build-up threatened not only Sri Lankan forces but also members of other groups sponsored by India. The LTTE was allowed to exploit the situation to the hilt. Under the very nose of Indian authorities, the LTTE transferred both men and material from Tamil Nadu to the Jaffna peninsula. The LTTE built up fortifications close to isolated military bases and mined roads. Before the LTTE resumed hostilities, LTTE leader Velupillai Prabhakaran wanted to eliminate rival groups. He resented rival Tamil groups having direct links with Indian Intelligence. The stage was set for the massacre of Tamil youth in the Jaffna peninsula.

Addressing the media at ‘Rakshana Mandiraya’ in Colombo, Minister Athulathmudali declared that major terrorist groups including the LTTE, had agreed to abide by the Indian initiated peace effort. In spite of serious misgivings, Minister Athulathmudali claimed that a ceasefire would come into operation with immediate effect (Five big terrorist groups for cession of violence––Lalith – The Island June 19, 1985).

On June 26, 1985, nine days after the declaration of ceasefire, terrorists shot dead T. Anandarajah, the much respected principal of St. John’s College, Jaffna, outside his school. Anandarajah was accused of having organised cricket matches between his students and the army.

One-time Joint Operations Commander, General Cyril Ranatunga has explained the LTTE operation in the wake of the June ceasefire in a piece titled Negotiating Peace in Sri Lanka: the Role of the Military (Negotiating Peace in Sri Lanka: Efforts, Failures and Lessons-an International Alert publication edited by Dr. Kumar Rupesinghe in February 1998).

The ceasefire was intended to confine troops, especially those deployed in the Jaffna peninsula, to their barracks, instead of taking tangible measures to cease violence ahead of the Thimpu talks. Terrorists mounted a series of attacks during this period. The police went on the rampage in Vavuniya during the second week of August 1985, after a roadside bomb blast claimed the lives of five personnel. The police were accused of killing nine civilians.

Much to the embarrassment of India, Tamil groups declared that the Thimpu talks wouldn’t meet their aspirations. They ordered protests in Jaffna and Vavuniya ahead of the first round of talks. In fact, they participated in the talks due to Indian pressure, though India portrayed the Thimpu confab as a success. Although the TULF participated in the deliberations, it couldn’t say anything contrary to the position taken by the armed Tamil groups.

Thimpu talks collapse

The terrorists declared that the continuation of the negotiating process would entirely depend on President JRJ accepting four prerequisites which they called invariable terms for any meaningful solution. They demanded the recognition of the four demands before the Thimpu talks could proceed. Declaring the four conditions as basic non-negotiable principles, they called for:

(A) the recognition of Tamils of Sri Lankan origin as a distinct nation with the inalienable right to self determination;

(B) the recognition of Northern and Eastern Provinces as a Tamil homeland;

(C) recognition of the right of self determination of the Tamil nation and lastly

(D), the granting of citizenship to all Tamil residents in Sri Lanka. The TULF, too, supported the demands put forwarded by the armed groups.

It was widely believed that India had been fully aware of the four demands. The set of conditions was meant to ensure a quick collapse of the Thimpu talks.

President JRJ declined to the give in to Indian initiative hence two rounds of talks in July and August failed to break the deadlock.

The terrorists wouldn’t have scuttled the Thimpu initiative unless they had been convinced that India would continue to sponsor them whatever the outcome at the negotiating table. Even during the abortive Thimpu deliberations, terrorists continued to receive military training in India. The TELO, the LTTE, the PLOTE, the EPRLF and TULF took part in the Thimpu deliberations.

Convinced of their growing military capability, thanks to India, the terrorists felt that they could overwhelm government forces in the Jaffna peninsula. Having torpedoed the Thimpu talks, TULF representatives as well as those members of various terrorist groups returned to India. Those Indians running the Sri Lankan project believed they could still control the growing terrorist movement. Although the TULF remained faithful to its Indian handlers, the Gandhi administration increasingly found it difficult to control the LTTE. At the conclusion of the Thimpu talks, the LTTE declared in no uncertain terms that it should have special status in recognition of its military capability. Prabhakaran was moving towards calling his outfit as the sole representative of Tamil speaking people. Although other Tamil groups sensed a hardening of the LTTE’s position, they never expected a project to annihilate them.

THIMPU TALKS – JULY/AUGUST 1985

Introduction

|

|

In June 1985, at the initiative of the Government of India, the leaders of the Tamil militant movements which were engaged in an armed struggle for the establishment of a separate Tamil Eelam state in the North and East of the island of Sri Lanka, agreed to a ‘cease-fire’ as a preliminary step to creating a ‘congenial’ atmosphere for ‘peace talks’. Phase I of the talks commenced on 8th July 1985 and concluded on 13th July 1985. Phase II of the talks commenced on 12th August 1985 and concluded on 17th August 1985. The venue of the talks was Thimpu, the capital city of the Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan.

The Tamil Delegation consisted of representatives from the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF), Tamil Eelam Liberation Organisation (TELO), Eelam Revolutionary Organisation (EROS), Peoples Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam PLOTE) and Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF). The LTTE, EPRLF, TELO and EROS were also constituent members of the Eelam National Liberation Front.

|

|

In Phase I of the talks Mr.Anton and Mr. Lawrence Thilagar represented the LTTE.

Mr.A.Varadarajah Perumal and Mr.L.Ketheeswaran represented EPRLF.

Mr.Charles Antonidas and Mr.Mohan represented TELO.

Mr. Rajee Shankar and Mr.E.Ratnasabapathy represented EROS.

PLOTE was represented by Mr.Vasudeva and Mr.Dharmalingam.Sitharthan.

The TULF delegates were Mr.M.Sivasithamparam, Mr.A.Amirthalingam and Mr.R.Sampanthan.

In Phase II there was one change in the composition of the Tamil delegation – Mr.Nadesan Satyendra and Mr.Charles Antonidas represented TELO.

The Thimpu negotiations represented a watershed in the Tamil Eelam struggle for more reasons than one.

Firstly, the recognition accorded to the armed resistance movement by both the Sri Lankan government and the Indian government and the open participation of the representatives of the armed resistance at negotiations with accredited representatives of the Sri Lankan government, furthered the legitimisation of the armed struggle of the Tamil people in the international arena.

Secondly, the Declaration made by the Tamil delegation at Thimpu, which has come to be known as the Thimpu Declaration, and the statement made by Nadesan Satyendra at the Talks on 14 August 1985 and the Joint Response of the Tamil Delegation on 17 August 1985, served to crystallise the central issues of the Tamil struggle and provide a mobilising platform for the continuation of the struggle.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thimpu_principles

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.