Sri Lankan Tamil Struggle

Chapter 5

by T. Sabaratnam

August 27, 2010

Tamils lose sovereignty

A journalist who reported the Sri Lankan ethnic crisis for over 50 years

The Portuguese captured the Jaffna Kingdom by defeating King Sankili in battle. Thus unlike the low country Sinhalese who lost their sovereignty through a deed of gift Sri Lankan Tamils lost their freedom because they were conquered by the Portuguese.

Malvana Convention

When the Portuguese landed in Galle on November 15, 1505 Kingdoms of Kotte, Kandy, Jaffna and six more chieftaincies ruled in Sri Lanka. The Kotte Kingdom ruled the southern and western lowlands, the Kandyan Kingdom the mountainous central region, Jaffna Kingdom the north and the northern portion of the east and the chieftaincies the region between the Kingdoms of Kotte and Jaffna and the east and south.

Portuguese historian Joao de Barros in his book ‘The History of Ceylon from the Earliest Times to 1600 AD (Page 37) describes the political divisions of Sri Lanka as it existed during the arrival of the Portuguese in the following words:

At present what is to the purpose of our history is to know that it is divided into nine states, and each of these is called a kingdom.

A Portuguese ship

Barros admits the biggest of them were Kotte, Kandy and Jaffna and says that each of them claimed that they were the rulers of the entire island.

The three kingdoms and the chieftaincies lost their sovereignty during the period of 310 years; Kotte in 1597, Jaffna in 1619, Vanni in 1802 and Kandy in 1815. Kotte went under the Portuguese through a deed of gift and Jaffna passed into Portuguese control when it lost the battle with them. Vanni and Kandy were captured by the British army.

Kotte fell on the lap of the Portuguese due to the infighting in the Royal family. The Portuguese who were interested in the spice trade, especially in cinnamon, found that the Kotte Kingdom enjoyed the monopoly in that trade. The Portuguese commander Lourenço de Almeida who realized the strategic and commercial value of forging a close trade relationship with the rulers of Kotte proceeded to Kotte and met King, Dharma Parakramabahu, who gave him a friendly welcome.

The Portuguese soon entered into an agreement with Dharma Parakramabahu who agreed to provide them with regular supply of cinnamon. In 1518, Vijayabahu VI who succeeded Dharma Parakramabahu permitted the Portuguese to build a fort in Colombo to process cinnamon. In return, the Portuguese assured the King military help to defend his kingdom from enemies. Thus, the Portuguese became the allies of the Kotte Kings. This arrangement continued until 1551.

In that year, this relationship changed due to the succession dispute in Kotte into which the Portuguese were drawn in. Vijayabahu VI had three sons, Bhuvanekabahu, Rajasimha and Mayadune, and an adopted son Devarajasinghe. Vijayabahu VI and his ministers groomed Devarajasinghe to be the next king. The three sons revolted against Vijayabahu VI and laid siege to Kotte in 1521. Vijayabahu VI surrendered but was killed by the sons.

The brothers divided the Kingdom of Kotte among themselves and the eldest of them, Bhuvanekabahu was crowned the king of Kotte under the name Bhuwanekabahu VII and reigned till 1551. The portion Ravigama went to the second son Rajasimha and the other portion Sitavake to Mayadunne.

Mayadunne the most energetic and resourceful of the three brothers wanted to unite Kotte under his rule. He attacked Kotte but Bhuvanekabahu VII sought assistance from the Portuguese to protect his regime. The Portuguese provided the protection on condition that he becomes subservient to them.

Rajasimha, the ruler of Rivigama died in 1538 and Mayadunne annexed it to Sitavake with Bhuvanekabahu VII’s consent. But in the next year he attacked Kotte but was beaten back by the Kotte forces which were backed by the Portuguese. Though humiliated, Mayadunne’s popularity rose among the people of Kotte who resented the Portuguese trade practices and religious conversion activities.

Fearing that Mayadunne might overthrow him and his grandson Dharmapala Pandaram whom he wanted to be his successor, Bhuvanekabahu VII requested the Portuguese in 1543 to formally approve his grandson as his successor. In his letter, he addressed the Portuguese King João III, as “my Lord” or “my Senhor,” and in a letter to the Governor in Goa, he said: “I am a Vassal of the King my Lord.” Following this request, the Portuguese placed a strong guard under an officer at the King’s Palace.

Bhuvanekabahu VII sent a golden statue of his infant grandson to Lisbon and secured the Portuguese monarch’s guarantee that his grandson would succeed him to the throne of Kotte. When Bhuvanekabahu VII died in 1551 the Portuguese installed Dharmapala Pandaram on the throne of Kotte as a nominal sovereign. Thus the Portuguese became the protectors of Kotte in 1551.

In 1557 King Dharmapala was baptized as Don Juan Periya Bandara. The Buddhist monks and a large number of Buddhist laymen who were displeased that their king had become a non – Buddhist took the Sacred Tooth Relic and moved to Sitawaka, the Kingdom of Mayadunne.

Mayadunne and Prince Tikiri attacked Kotte and Colombo fort simultaneously. The Portuguese who realized that it was difficult to defend both Kotte and Colombo at the same time abandoned Kotte and shifted to Colombo taking King Dharmapala with them. The Kingdom of Kotte which had been the capital for over 150 years declined with the abandoning of Kotte by the king in 1565.

King Dharmapala who reached Colombo became a puppet ruler in the hands of the Portuguese.

On 12 August 1580, due to the insistence of the Portuguese, King Dharmapala vested the Kingdom of Kotte in the Portuguese by a deed of gift. One clause in the deed of gift was that if Dharmapala dies without an heir the Kingdom of Kotte should pass to the Portuguese. Dharmapala died on 29 May 1597 without an heir and the Kingdom of Kotte became a Portuguese possession.

Two days after Dharmapala’s death General Jeronimo De Azevedo held an assembly of chiefs of the Kotte Kingdom in Malwana and hoisted the Portuguese flag and proclaimed that the Kingdom of Kotte had passed on to the King of Portugal. In return, he assured the chiefs that the administration would be carried on according to the traditional laws and customs that hitherto existed. From then onwards the Portuguese became the lawful heirs to the Kingdom of Kotte.

The Portuguese made the transfer of the Kotte Kingdom legally valid through a treaty signed by King Philip 11 of Spain who was also king Philip 1 of Portugal, in his capacity as king of Portugal and the nobility of Kotte who were present in Malvana. In terms of this convention, the nobility of Kotte, on behalf of the people of Kotte freely accepted the sovereignty of King Philip and swore fealty to him as King of Kotte, by virtue of the last will and testament of the last king of Kotte, Don Juan Dharmapala 1, who died in 1596.

The contracting parties in this treaty were the King of Spain and the Indies, the most powerful ruler on earth during that period, as king of Portugal, and the representatives of the people of the kingdom of Kotte, an independent, legally constituted, diplomatically recognized, the political entity which in other words, a sovereign state. The chiefs swore allegiance to the king of Portugal and, in return, were assured that their laws and customs would be left inviolate.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0e/Cankili_I.jpg/220px-Cankili_I.jpg

Statue of Sankili

Nallur Convention

The Portuguese captured the Jaffna Kingdom by defeating King Sankili in battle. Thus unlike the low country Sinhalese who lost their sovereignty through a deed of gift Sri Lankan Tamils lost their freedom because they were conquered by the Portuguese.

When the Portuguese landed in Sri Lanka in 1515 Jaffna Kingdom was ruled by Pararajasekaran (1478-1519). The Portuguese did not show any interest in the Jaffna Kingdom as cinnamon or spices in which they traded were not available there. Their attention was drawn to the Jaffna Kingdom accidentally. One of their cargo ships was shipwrecked near Jaffna coast in 1543. Sankili, who succeeded Pararajasekaran in 1519 and ruled till 1561 confiscated the cargo following the custom that all ships stranded in the shallow sea belonged to the ruler of the land adjoining the sea. He also imprisoned the survivors. The Portuguese contacted Sankili and made him pay them the value of the goods and release their men.

Their next contact with the Jaffna Kingdom was also in the same year. Early that year Fr. Francis Xavier, a Portuguese Roman Catholic priest of the Franciscan Order, visited Mannar and converted 600- 700 fishermen and pearl divers. Sankili saw in this a grave threat to Jaffna’s economy and security. He realized that the immensely valuable pearl fisheries would be lost and Mannar would be turned into a bridgehead for a Portuguese invading army.

In July 1544, Sankili led an expedition to Mannar and demanded all the converts to return to Hinduism. When they refused, he slaughtered them. Fr. Francis Xavier who was stationed in Goa where the Portuguese had their headquarters appealed to the Portuguese Viceroy to punish the Jaffna King. The Portuguese sent an army commanded by Martin Alphonsus De Souza and it camped in Delft but it left when Sankili offered valuable presents.

The Portuguese sent another expedition of 77 ships with 4000 troops in 1558 under Constantine de Braganca and captured Jaffna. Sankili withdrew to Pachilaipalli. He then made peace with the Portuguese offering to give them 12 elephants and 1200 sovereigns every year and returned to power, but he lost Mannar. Thus, he lost the pearl fishery and the control of the trade and shipping routes in the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Straits, a major source of revenue for his Kingdom. The Portuguese built a fort in Mannar making use of the building material they obtained by demolishing the Thirukeetheswaram temple in Mannar.

Sankili continued his policy of resisting Portuguese intrusion. He joined forces with the Sinhalese kings who resisted Portuguese incursions. He sent a detachment of his army to fight along with the Sinhalese army led by the Sittawaka king Mayadunne. That expedition failed. Then when Vidya Pandara fled to Jaffna with his son after falling out with the King of Kotte and the Portuguese, Sankili welcomed him warmly. Prof. S. Pathmanathan says in his paper “The Kingdom of Jaffna before the Portuguese conquest (Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka) that Vidya Bandara was killed while he was within the Veeramakali Amman kovil by the Sinhalese in Jaffna who revolted. Sankili deeply regretted his death and built a memorial, the Puthar Rasar Kovil in the northern precinct of Nallur. Sankili also permitted the transport of men and material through his kingdom to Kandy.

Portuguese were angered by Sankili’s anti- Portuguese activities. To put an end to them and to seal off the supply route to Kandy and to take complete control of the trade routs that ran through Palk Straits Portuguese captured the Jaffna Kingdom. How Sankili died is not clear. The Jaffna University publication Yalpana Irachchium says with definiteness that Sankili was not captured by the Portuguese. But Portuguese documents say he was captured.

The History of Ceylon by M.G. Francis, an abridged translation of Prof. Peter Courtenay’s work, ‘The Temporal and Spiritual Conquest of Ceylon’ (1658) maintains that he was captured. It says he was sent to Colombo and then to Goa where he was tried for high treason and for the many crimes he had committed and condemned to death.

Portuguese interference in the affairs of the Jaffna Kingdom increased with the death of Sankili but they were not powerful enough to impose their will. Thus there was confusion and instability there. Sankili’s son Puvi Raja Pandaram, to whom Sankili handed over the kingdom ruled for four years (1561- 1565).

Periya Pillai (1565-1582) ascended the throne in 1565 replacing Puvi Raja Pandaram. How that happened is not clear but Portuguese records suggest that they had an important role to play. Periya Pillai at the start acted on the directions of the Portuguese. They made him to pay an annual tributary payment of ten tuskers or their worth in money.

http://www.sangam.org/2008/07/images/kandydistr.gif

The map shows the territories administered by the Dutch in 1796. They were Jaffna Commandant, Colombo Commandant and Galle Commandant. The rest of the country was under the Kandyan Kingdom.

The Portuguese took over the administrative authority of the Jaffna Kingdom in 1570 but permitted Periya Pillai to rule. He was overthrown 1582 by Sankili’s son, Puviraja Pandaram. Like his father, Puviraja Pandaram followed an anti-Portuguese policy. He sought the help of the Zamorin of Calicut and attacked Mannar. But the expedition failed.

In 1591, the Portuguese sent a large army under Furtado Mendonca to curb Puviraja Pandaram’s activities. It landed in Mannar and marched to Jaffna, massacred 800 of Puviraja Pandaram’s soldiers and killed Puviraja Pandaram.

Mendonca then summoned the Tamil chiefs and the Mudaliyars for a convention at Nallur. He asked the assembled chiefs to submit to the King of Portugal’s suzerainty. He declared that he would maintain the distinct laws and customs of the Tamil kingdom. The Tamil chiefs accepted the offer and took the oath of allegiance to the king of Portugal. The ceremony was followed by the signing of a treaty. King Philip 111 of Spain signed the treaty in his capacity of King Philip 11 of Portugal and the Tamil chiefs and Mudaliyars of the kingdom of Jaffna on behalf of the people of Jaffna.

The Tamil chiefs freely acknowledged through this treaty the sovereignty of King Philip and swore fealty to him as King of Jaffna, by virtue of the conquest of the kingdom by the Portuguese forces in 1616. As in the Malvana Convention, the contracting parties were the King of Spain, as king of Portugal, and the representatives of the people of the kingdom of Jaffna, an independent, legally constituted, diplomatically recognized, political entity – a sovereign state.

The Portuguese commander on the advice of the chiefs placed on the throne Ethirmannasinghan, the youngest son of Periya Pillai. He has crowned the king of Jaffna in the name of the King of Portugal. He took in accordance with tradition the royal name Pararajasekaran.

By these two treaties the Crown of Portugal came into possession of two separate states of Kotte and Jaffna, and they were so governed by the Portuguese crown as two territories. The budgets and statements of income and expenditure of the two territories were submitted to the treasury in Lisbon as two separate records, throughout the period 1618 to 1658.

Manthri Manai: The surviving portion of the Minister’s mansion Jaffna Sri Lanka http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/16/Mantrimanai.jpg/220px-Mantrimanai.jpg

Manthri Manai: The surviving portion of the Minister’s mansion

Ethirmanasingham too yielded to Hindu pressure and adopted an anti-Portuguese stand. He obtained help from Nayakas of Thanjavur and struck an alliance with the Kings of Kandy, Vimaladharmasuriya I (1593-1604) and Senarat (1604-1635) who were anti-Portuguese. He died in 1617.

On his death, his nephew Sankili Kumaran seized the crown. The Portuguese captain who was in Mannar could not interfere. He exacted two promises from Sankili Kumaran: to permit the spread of Christianity and not to aid the Sinhalese rebels who were resisting the Portuguese rule. The Portuguese exacted the second promise because they were at that time interested in capturing the Kandyan Kingdom.

Sankili Kumaran did not keep his word as the people of his kingdom was resisting religious conversion. He sought help from Ragunatha Nayakar of Thanjavur to oppose the Portuguese. He also made attempts to contact the Dutch who had landed in Batticaloa. The Portuguese considered this as treachery and sent an army to Jaffna to punish Sankili Kumaran.

The Portuguese army which travelled by land and sea was under the command of Oliveria. He sent three demands to Sankili Kumaran. They were: to surrender all the troops that came from Tanjavur; to surrender Varuna Kulattan, the Karava chief and to pay all money, he owed to the Portuguese sovereign. Sankili Kumaran refused to comply and the Portuguese army entered Jaffna. His forces fought back valiantly but were beaten at the Battle of Vannarpannai.

Sankili Kumaran with his family set to sail to Thanjavur to seek assistance from Ragunatha Nayakar. The adverse wind blew his boat towards Point Pedro where he was captured. Sankili Kumaran and his family were arrested and taken prisoners by the Portuguese. They were first taken to Nallur; from there, he was sent to Colombo and then to Goa where he was imprisoned. In Goa, he was tried for high treason by the Portuguese High Court and sentenced to death. He was hanged in 1621.

Following the arrest of Sankili Kumaran Filipe de Oliveriya, the Captain Major of the Portuguese army was installed as the Governor of the Jaffna Kingdom. But the Tamils continued their resistance. A Tamil Karava chief invaded the Jaffna Kingdom but was beaten back.

Two more attempts were made to expel the Portuguese from Jaffna. An influential Karava chieftain, Sinna Meegampillai Arachie, laid siege to Nallur in March 1620 with the help of soldiers from Thanjavur and the rebels within Jaffna. Portuguese broke the siege and drove him back. Meegampillai returned again in November 1620 with soldiers from Tamil Nadu but the Portuguese prevented them from landing. The final attempt to drive the Portuguese away was made in December 1620. An army of 2000 soldiers from Thsmjsvur landed at Thondamanaru on 5 December 1620 under the command of Varuna Kulatan. The war dragged on till February 11, 1621, but the invaders were beaten back. The Jaffna Kingdom thus fell into the hands of the Portuguese and the Tamils lost their sovereignty.

Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism

The Jaffna Kingdom that ruled northern Sri Lanka for 404 years (1215-1619) generated among the Sri Lankan Tamils a sense of a separate identity. They began to feel that though they are Tamils and shared with the Tamils in Tamil Nadu and other parts of the globe a Tamil identity they also possessed a distinct and separate identity: a Sri Lsankan Tamil identity. Professors K. Kailasapathy and K. Sivathamby, both of the Jaffna University, called that was the starting point of Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism.

Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism is based on historical, linguistic, religious, social and cultural factors. The Sri Lankan Tamils are proud of their history, especially of the achievements of the Jaffna kingdom. They are proud that the Jaffna Kingdom was the last Tamil- Hindu state that existed in the world. The last Tamil- Hindu state of South India was the Pandiya kingdom which was destroyed due to the Islamic invasion in 1334 AD. The Jaffna Kingdom was the only Tamil- Hindu state in the world from 1334 to 1619.

Linguistically, though Sri Lankan Tamils spoke Tamil like the rest of the Tamil people they had preserved the ancient Sangam words and usages. Due to that Sri Lankan Tamils have developed a separate dialect. Sri Lankan Tamils have developed their own literature while contributing to the general development of Tamil literature. In some areas, Sri Lankan Tamils have paved the way for the development of Tamil literature. Jaffna initiated the Hindu and Tamil revival movements in the mid- 19th Century.

In the literary field too Jaffna excelled. The kings encouraged education, writing and translating literary works and books on medicine. They organized Tamil Sangam on the lines of the Madurai Tamil Sangam. They also started a library called the Saraswathy Mahal in Nallur. It served as the royal repository of all literary output of the kingdom.

In religion too the Sri Lankan Tamils have developed a separate identity during the period of the Jaffna Kingdom. They followed the Saiva Siddantha practices as opposed to the Brahmanical practices of Tamil Nadu. Sri Lankan Tamils give importance to Thai Pongal, the festival of agriculturists, while Tamils in Tamil Nadu give importance to Dipavali. They give more importance to Tamil devotional hymns.

Jaffna kings had encouraged the study of medicine and astrology. Sri Lankan Tamils have developed the Siddha system of medicine. They have also developed a different social structure. Brahmins do not play an important role in society. Sri Lankan Tamils have also developed their own system of law called Thesavalamai.

Sri Lankan Tamils, thus, have developed a separate identity and wish to retain it. As Sivathamby effectively said, “Sri Lankan Tamils want to be Tamils and Sri Lankans.”

Separate Administrations

The Portuguese implemented Malvana and Nallur Conventions. The areas under the Kotte and Jaffna Kingdoms were administered as separate units. Portuguese historian Father Fernao De Queiroz in his book Temporal and Spiritual Conquest of Ceylon Volume I page 5 gives the extent of the area that came under the Jaffna Kingdom. He said it comprised the Jaffna peninsula and Vanni and extended from Mannar in the west to Trincomalee in the east.

The Portuguese brought the kingdoms of Kotte and Jaffna under the control of the Kingdom of Portugal and the King of Portugal became the monarch of the people of Kotte and Jaffna. The Portuguese king placed the administration of Kotte and Jaffna under his representative, the Viceroy at Goa. Thereafter, all the major decisions concerning the governance of Kotte and Jaffna were taken at Goa. The Viceroy’s representative, Captain-General of the Conquest, who resided in Colombo, became the virtual ruler of Kotte and Jaffna.

The Portuguese honouring their obligations under the Malvana and Nallur conventions administered the territories of Kotte and Jaffna separately. Separate officials called Captain Majors were appointed to administer the two territories. They were assisted by revenue officers called Factors who functioned as the Treasurer, Auditor and Chief Judicial Officer of each territory. A group of Portuguese officials who headed the various departments worked under him. The Ecclesiastical affairs of Kotte and Jaffna were made part of the diocese of Cochin, whose Bishop administered the two territories through separate Vicar Generals.

In Jaffna and Kotte, the Portuguese retained the traditional administrative machinery of each territory to run the ground level administration. These officials were required to adopt Roman Catholicism to enable them to continue to hold their posts. The Sinhalese and Tamil aristocracy which enjoyed tremendous power and influence under the traditional administrative system of Kotte and Jaffna was thus relegated to secondary positions. The Portuguese also tried to cut down their numbers.

The Portuguese turned Kotte and Jaffna into generators of revenue to enable them to finance their administration, fund their military operations and support their religious missionary activities. They increased the revenue by raising the existing taxes, duties and levies, by introducing new taxes, duties and levies and by streamlining revenue collection.

The Portuguese taxation was heavier in Jaffna than in Kotte and Abeysinghe, in his study of Portuguese rule in Jaffna says that they turned Jaffna into a money machine. The difference in treatment was mainly due to the submissive nature of the Jaffna administrators and the people and due to constant opposition, the Portuguese faced from the Sinhala people who supported the attacks by the Sitavaka and Kandyan rulers. The Portuguese were also under pressure from the Dutch in the south during the latter part of their rule.

Cinnamon was the prime item of trade in Kotte. In Jaffna the Portuguese introduced the cultivation of tobacco zs the commercial crop.

Catholic missionary activity began in the Jaffna Kingdom before its annexation to the Portuguese crown. Franciscan friars entered the kingdom soon after the Portuguese invasion of Jaffna in November 1591 and turned their attention to the influential administrators, mudaliyars to the village headman. According to Portuguese records, they used the extensive powers of patronage and preference the Portuguese officials enjoyed in granting appointments and promotions to the people to promote Christianity. Land-owning aristocracy was the other group that was compelled to adopt Roman Catholicism.

In 1622, members of the Jesuit order entered Jaffna and founded a college and used it as their headquarters. The Portuguese administrators decided the next year to divide the Jaffna peninsula into 42 parishes and allocated 24 to the Franciscans and the balance to the Jesuits. They sent the solitary Dominican who was already working in Jaffna to Kotte where others of his order had already established their presence. By 1634, all the parishes in Jaffna were functional.

The reports the two missionary orders had filed with their headquarters in the 1640s say that all the people of the Jaffna peninsula had embraced Roman Catholicism. One of the Portuguese officials had said just before the Portuguese rule ended that Jaffna was “wholly Christian”. It is reasonable to infer from these reports that during the latter part of the Portuguese rule no one practised Hinduism openly.

A Portuguese-built Church at Mallakam in Jaffna Peninsula.

Portuguese built Church of Mallgam

The Portuguese in their zeal to convert the entire population under their rule carried out general baptisms and mass conversions. Abeysinghe, quoting Portuguese officials Trinidade and Queiros says that a general baptism in a village was conducted thus: the arrival of the Portuguese missionaries was announced by the traditional tom tom beaters. When the people assembled, the Portuguese missionaries asked them to reject the “false” gods they were worshipping and accept “one true God”.

Abeysinghe adds that that was not a request but a command backed by the authority of the Portuguese government for the priests would invariably be accompanied by the local Portuguese officials and the native chiefs. “Fear of a fine or corporal punishment with cane and stock would ensure their regular attendance at church on Sundays and feast days,” Abeysinghe adds.

The Portuguese emphasis on proselytization spurred the development and standardization of educational institutions. Mission schools were opened as a means of conversion where the medium of instruction was Portuguese and Tamil. The Franciscans founded 25 parish schools and the Jesuits 12. They also established colleges for higher education in the Jaffna peninsula. In these schools religion, good manners (viores), reading, writing, arithmetic, singing, and Latin were taught. Education was free. For a while, Portuguese became not only the language of the upper classes of Sri Lanka but also the lingua franca of prominence in the Asian maritime world.

The Portuguese destroyed every Hindu temple and the Saraswathy Mahal library, the royal repository of all literary output of the kingdom. The first to suffer was the historic Thiruketheeswaram temple of Mannar. The rocks and bricks obtained from that temple were used to build the fort in Mannar. Nallur Kanthaswamy temple suffered next. Jaffna Fort was built using the building material obtained from it.

In the words of Fernao De Queiros, the principal chronicler of Portuguese colonial exploits in Sri Lanka, the people of Jaffna were “reduced to the uttermost misery” during the Portuguese rule.

Treaty of 1658

The Dutch East India Co. (VOC) conquered the states of Jaffna and Kotte in 1658. The VOC ratified its conquest of the Portuguese possessions in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) and other parts of Asia by signing a treaty with Portugal. The treaty known as the Treaty of 1658 was signed by King John 1 of Portugal and the VOC. The Portuguese territories in Sri Lanka, Kotte and Jaffna, were described separately in two distinct schedules.

The Dutch ousted the Portuguese from Sri Lanka in June 1648 and ruled until 1798 when they were expelled by the British. Like the Portuguese, the Dutch administered the two territories separately.

The Governor was the head of the administration of the Dutch territories in Sri Lanka. He was assisted by a council that consisted of the Chief Administrator, the Controller of Revenue, the Disawa of Colombo, the chief military officer, the Fiscal (Public Prosecutor), and five other officers who headed the principal departments at the headquarters. The Governor was obliged to take the advice of the council.

For administrative purposes, the territory under their rule was divided into three divisions – Colombo, Galle and Jaffna. Colombo was the largest unit spreading from Kalpitiya in the north to the river Bentota in the south. Galle and Jaffna were administered by separate commanders assisted by their respective councils. This restricted the territory of the Tamils to the north and east. Some of the territories in the west and south which were earlier under the Kingdom of Jaffna were annexed to the Sinhala areas.

The internal administration of each division was under the official named dissava. Jaffna dissava was in charge of Mannar, Trincomalee and Batticaloa. Officials called Superintendents were placed in charge of these areas and they functioned under Jaffna Dissawa. All the officials above the rank of dissavas were Dutchmen. There were about 3000 Dutch officials in the government service. Like under the Portuguese, the Sinhala and Tamil officials were given only subsidiary positions.

The Dutch, like the Portuguese, retained the old system of government inherited from the native kings. The dissavanis were divided into korala, pattu and gama. The mudaliyars, Koralas, athukoralas were in charge of these divisions. Another official named vidane was in charge of the day-to-day functions of the villages.

In administration and judicial systems, the Dutch, like the Portuguese, used the Sinhalese language in the Sinhala areas and the Tamil language in the Tamil areas. They preserved the two linguistic zones that existed during the period of the native kings.

Like the Portuguese, the Dutch did not make any fundamental changes in the administration, customs and social structure of the people. Like the Portuguese, the Dutch held all the top posts themselves and thus reduced the locals to secondary positions.

The Dutch contributed to the evolution of the judicial system of Sri Lanka. They recognized and codified the indigenous laws and customs that did not conflict with Dutch-Roman jurisprudence. Thesavalamai, the Tamil legal code of Jaffna, Mukkuvar law, legal practices of the people of Batticaloa, and Muslim law were codified in this manner. In the Low Country, courts applied Roman-Dutch law, thus modifying traditional notions of property and affecting family structures.

The Dutch implemented their religious policy rigorously in Jaffna. When they took control of the peninsula there were 20 Catholic churches and some of them were architectural beauties. They took them over. There were 34 Hindu temples which escaped the Portuguese frenzy of destruction. They destroyed them.

The Dutch built several churches in Jaffna. One of the Dutch churches, which was built within the Dutch fort of Jaffna stood there intact till the beginning of the 1990s and fell into ruins together with the fort due to heavy fighting around this area

Tellipalai Church was one of the first Dutch Reformed churches established in the Jaffna peninsula. It was opened in August 1658 by Ven. Philip Pauldias. He also opened a school in its compound. This church and the school were the cause for Tellipalai’s advance in the fields of religion and education.

The Dutch administered Jaffnapattnam in Tamil and Tamil occupied a prominent place in their documentation. They used Tamil to propagate their religion, Protestantism, among the people. Their pastors and preachers studied Tamil and communicated with the people in Tamil. The Thesavalamai Law was complied in Tamil. Their system of education too laid stress on developing the capacity to communicate in Tamil.

This environment coupled with the latent spirit of nationalism found expression, like in the Kandyan kingdom, in literary works. The mudaliyar community which had direct contact with the people and understood their real feelings were in the forefront of the literary revival.

Sinnathamby Pulavar, son of Vilvaraya mudaliyar, one of the 12 mudaliyars who helped in the compilation of Thesavalamai law, wrote two notable poetic works Kalvalaiyanthathi and Maraisaiyanthathi Senathiraya mudali wrote Nallaiyanthathi and Nallaivenba. He later played an important role in compiling the first Tamil dictionary published by the missionaries. Muthukumara Kavirayar, Viswanatha Sasthiriyar and Swami Ganapragasar played a pivotal role in the revival of Tamil literature. A popular literary form called ammanai was used during this period for religious propagation. Fr; Ganapragasar had collected twenty such works.

Several dramas were written and staged during the Dutch period. They were based on the Hindu epics Ramayana and Mahabharata and on Christian topics. Ganapathy Iyer wrote three popular dramas Alangararupa Vatakam, Adhirupavathi Vilasam and Valapeeka Natakam. Muthukumarasamy Pulavar rendered the life of Devasakayam Pillai, a South Indian Roman Catholic, who sacrificed his life defending his faith. He titled the drama Devasakaya Batakam. Poothathamby Natakam which depicted the story of a controversial event that happened during Portuguese rule emerged as a very popular drama which is acted even today

The encouragement the Dutch missionaries gave to the publication of Christian literature and the introduction of printing were the factors that motivated the revival of Tamil and Sinhala literature. A booklet that turned out to be the trailblazer for Tamil prose was Vetha Vina Vidai. Written in question and answer format it explained the basic tenets of Christianity, Arumuga Navalar, the Hindu revivalist of the mid-1850s adopted that format effectively. Christian pamphlets that explained the rules and regulations of the Dutch Reformed Church were very popular. The masterpiece of the Christian literature of that period was Thembavanikam authored by Fr. Constantine Besche.

The religious policy of the Dutch which was harsh on Roman Catholicism, Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam in the initial stages and tolerant in the final stages also left an impact on Sri Lankan society. Dutch who practised Protestantism banned all religious activities of the Roman Catholics soon after the expulsion of the Portuguese. The Dutch feared that the Roman Catholic population would aid the Portuguese to recapture Sri Lanka. They also feared that unless the Roman Catholics were converted to the ‘true religion’ of Protestantism (Calvinism) they would fall back to their original religions of Buddhism and Hinduism.

The Catholic churches were either converted into Protestant churches or destroyed. They banished the Catholic priests and declared giving shelter to Catholics, Buddhists and Hindus a capital offence. Buddhist and Hindu ceremonies too were prohibited.

The Dutch also followed the Portuguese policy of using education as a tool to propagate their religion. Unlike the Portuguese, the Dutch made use of education to promote the welfare of the local people. The Dutch period is important in the history of educational development in Sri Lanka.

The Dutch replaced the Catholic parish schools established during the Portuguese period with schools affiliated with the Dutch Reformed Church. Education was almost entirely in the hands of the priests.

The emphasis the Dutch gave to education and to the use of Sinhala and Tamil generated the necessary environment for literary activity. That was particularly so in Jaffna, Vanni and Kandy where the nationalist spirit was steadily flourishing.

Parallel to the Tamil literary revival was that of the Sinhala literature in which development the two centres of Sinhala nationalism- – Kandy and Matara – played a significant role. In Kandy, Valivita Saranankara, who lived during the reign of Kirti Sri Rajasimha, revived the classical Sinhala tradition which flourished in Kotte. A major part of the literary activity was in writing the biographies of kings and nobles in prose and poetry and the revival of folk tradition.

The Dutch established the first printing press of Sri Lanka in Colombo in 1737 with the objective of printing Christian literature in Sinhala and Tamil. The press was first used to print posters that announced the orders and proclamations issued by the Dutch East India Company. The first book printed in Sinhalese was: Singaleasch Gobasdo – Book, It was printed in 1737. The second printed in Sinhalese in the same year was a manual on the cultivation of pepper. Its Tamil translation was published in 1741. Several books on religious matters were published in Sinhala and Tamil till the Dutch rule ended in 1796.

The compilation of the historical work Yalpana Vaipava Malai took place during the Dutch period. It was composed by Mailvagana Pulavar of Mathagal in 1796, the last year of Dutch rule at the request of Jan Maccara, the Dutch Governor of Jaffna. His authorities were earlier writings such as the Kailaya Malai, Vaiya Padal, Pararajasekaran Ula and Raja Murai (Royal Chronicles) the oldest of which was certainly not earlier than the Fourteenth or the Fifteenth Century AD, Yalpana Vaipava Malai, Rasanayagam says, “Yalpana Vaipava Malai was a faithful account of all that was available at that time.” Yalpana Vaipava Malai was printed several years later and was translated into English by C. Britto.

Treaty of Amiens

By the end of the 18th Century, Dutch power was on the decline and the power of Britain and France was on the rise. They tried to capture the Dutch colonies. The British East India Company formed at Madras in 1639 captured Tamil Nadu and the adjoining areas established the Madras Presidency. In 1796 the east India Company captured the territories controlled by the Dutch in Sri Lanka.

France which had captured Pondicherry and Karaikal on the western coast of South India tried to take control of the Dutch possessions in Sri Lanka. This competition was brought to an end on March 25, 1802, when the French Republic and the United Kingdom signed the Treaty of Amiens. The treaty was signed by Joseph Bonaparte and Marquess Cornwallis on behalf of France and the United Kingdom. Under the treaty, the United Kingdom recognised the French Republic which it had claimed as part of its possession from 1340.

To that treaty, the territories under the control of the United Kingdom and France were annexed in a series of schedules. Jaffna and Kotte are listed in separate schedules. Anthony Hensman who wrote on this subject in the Daily Mirror two years ago says, “

A whole world of historical and political exploration and discovery is open to those genuine scholars, both of the majority and minorities, to examine the original documents, beginning with the Treaties of Malvana, Nallur and Kandy, subscribed by the ancient peoples of the country, under their time-honoured and traditional, separate and distinctive, historical and political identities, and extending to the treaties between the Portuguese crown and the V.O.C. of 1658, and between the latter and the British crown in 1803. If the protocol copies of these treaties are not with the Colombo archives, the originals would be with the archives in Lisbon, the Hague and London. The schedules and maps which form a substantive part of these treaties should make interesting and revelatory reading.

Kandyan Treaty of 1638

King Rajasimha II

The Portuguese which had established its control over Kotte tried to bring the entire country under its dominance. To tackle the Portuguese attempt Kandyan King Rajasinghe II worked out an agreement with the Dutch who were stationed at Batticaloa to protect his kingdom.

The treaty known as the Kandyan Treaty of 1638 was signed by William Jacobsz Coster, a commander and vice commander of the Dutch Naval Forces, for the Dutch East India Company and King Rajasinghe II on May 23, 1638, in Batticaloa. The treaty secured the terms under which the two nations would cooperate in defending the Kandyan Kingdom from the Portuguese. The treaty mentions the Kandyan Kingdom which the Portuguese were trying to capture as a nation.

The Kandyan Convention

The British East India Company that captured the Dutch territories in Sri Lanka administered them as part of the Madras Presidency. The British government, realizing the strategic importance of Sri Lanka decided to take them over from the company. It sent Fredrick North to take over the administration. It declared Sri Lanka a crown colony in 1802 and appointed North as the first British governor.

North decided to bring the entire island under the British rule and captured Vanni by defeating its ruler Bandara Vanniyan. His next target was the Kandyan Kingdom. While North was making secret preparations a plot was hatched by the most powerful chief of the royal court. Maha Adikaram Pilimatalawe. His plan was to obtain the help of the British to depose the king and take his place.

Pilimatalawe met North secretly at Sitawaka and requested the British to take possession of the Kandyan Kingdom and help him to be the king. In return, he promised liberal trade concessions. North did not evince interest in Pilimatalawe’s scheme. He decided to make use of the dissension in the royal court to bring the Kandyan Kingdom under British rule.

The King smelt the plot and broke away from the plotting Pilimatalawe. North started implementing his plan to take over the Kandyan Kingdom. He sent Gen. Hay Macdowall to Kandy to meet the king and negotiate a deal to make the Kandyan Kingdom a British protectorate. The king turned down the offer.

Lieut-Gen. Sir Robert Brownrigg assumed duties as the Governor on March 11, 1812. He decided to make use of the confusion in Kandy to capture it. He and his deputy D’Oyly received Ehelepola Maha Adikaram to succeeded Pilimatalawe at the Governor’s residence in Mount Lavinia. The Governor promised him his favour and protection if he rebelled against the king.

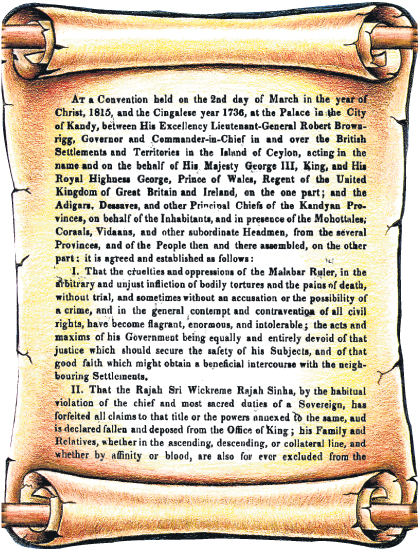

Art work of the Kandyan convention (English translation)

Ehelepola worked out the plan for a military attack on Kandy. The Governor declared war against the king of Kandy on January 10, 1815. A British division entered Kandy February 14, 1815, and took possession of the city and sent Ehelepola to capture the king. The king went into hiding but was soon discovered at a place closer to Meda Mahanuwara in Kandy.

Four days later the king was bound, plundered of his valuables and dragged away with the greatest indignity by the supporters of Ehelepola, and was brought to Colombo for deportation to Vellore in South India, where his consorts and other kith and kin were based.

Two weeks after the capture of the king, on March 2, 1815, the Kandyan Convention (treaty proceedings) was held in the same Audience Halll where the king used to preside. This time Governor Robert Brownrigg presided. The historic date was 2 March, 1815.

He received Maha Nilame Ehelapola, and the Dissawas led by Molligoda. Ehelepola, together with John D’Oyly of the British Civil Service who engineered the coup.

The treaty was read by D’Oyly in English and Mudaliyar de Saram in Sinhala declaring that Sri Wickrema Rajasinghe and all his family were forever excluded from the throne.

The Kandyans were assured that their new rulers would respect their laws, institutions and customs and that the religion of the Buddha would be inviolable.

Nobles who had assisted the British invasion were restored to the rule of their original provinces with the promise that their privileges and powers would be respected so long as they carried out their administration with the general policy of the British government.

Signatories to the Treaty were Governor Brownrigg, Ehelepola and the Dissawas Molligoda, Pilimatalawe the elder, Pilimatalawa Junior, Monerawila, Molligoda the younger, Dullewe, Ratwatte, Millawa, Galgama and Galegoda. The signatures were witnessed by D’Oyly, now a British resident in Kandy and Deputy Secretary James Sutherland.

Two further conferences were held at the Audience Hall. One week later Governor Brownrigg received the Ven. Kobbekaduwa Mahanayaka Thera of Malwatte and the Ven. Yatawatte Mahanayaka Thera of Asgiriya. He gave them his personal assurance on behalf of the British Crown that the Sangha would be protected and the temples held sacred.

This conference was immediately followed by another to discuss with the chiefs the return of the sacred Dalada to the temple of the Tooth and the tutelary deities to their sanctuaries in the Devasanghinda.

The Kandy Convention consisted 12 clauses. The summary:

- Sri Wickrema Rajasinha, the Malabari king to forfeit all claims to the throne of Kandy.

- The king is declared fallen and deposed and the hereditary claim of his dynasty, abolished and extinguished.

- All his male relatives are banished from the island.

- The dominion is vested in the sovereign of the British Empire, to be exercised through colonial governors, except in the case of the Adikarams, Disavas, Mohottalas, Korales, Vidanes and other subordinate officers reserving the rights, privileges and powers within their respective ranks.

- The religion of the Buddha is declared inviolable and its rights to be maintained and protected.

- All forms of physical torture and mutilations are abolished.

- The Governor alone can sentence a person to death and all capital punishments to take place in the presence of accredited agents of the government.

- All civil and criminal justice over Kandyan to be administered according to the established norms and customs of the country, the government reserving to itself the rights of interposition when and where necessary.

- Over non-Kandyans the position to remain according to British law.

- The proclamation annexing the Three and Four Korales and Sabaragamuwa is repealed.

- The dues and revenues to be collected for the King of England as well as for the maintenance of internal establishments in the island.

- The Governor alone would facilitate trade and commerce.”

The British kept their promise given to the Kandyans. It was administered as a separate unit till 1833 when the three territories- Kotte, Jaffna and Kandy were brought under a centralized administration. Kandy was a separate autonomous unit for 18 years (1815- 1833), Jaffna enjoyed that status for 214 years (1619- 1833) and Kotte for 237 years (1596- 1833).

Malvana Convention, Kandyan Convention and the Treaty of 1638 provide indirect proof for the separate autonomous existence of Jaffna for 214 years. Nallur Convention, Treaty of 1658 and Treaty of Amiens provide direct proof for Jaffna’s autonomy.

Next Friday: Birth of a Unitary State

https://www.sangam.org/2010/08/Tamil_Struggle_5.php?uid=4049

——————————————————————————————————————-

Sri Lankan Tamil Struggle

Chapter 6: Birth of a unitary state

by T. Sabaratnam,

September 3, 2010

| Herbert White, a British Government Agent in Badulla minuted in the ‘Journal of Uva’: “It is a pity that there is no evidence left behind to show the exact situation in Uva in terms of population or agriculture development after the rebellion. The new rulers are unable to come up to any conclusion on the exact situation of Uva before the rebellion as there is no trace of evidence left behind to come to such conclusions. If thousands died in the battle they were all fearless and clever fighters. If one considers the remaining population of 4/5 after the battle to be children, women and the aged, the havoc caused is unlimited. In short, the people have lost their lives and all other valuable belongings. It is doubtful whether Uva has at least now recovered from the catastrophe.” |

Cleghorn Minute

Last week I highlighted three conventions and three treaties which establish that the Portuguese administered the territory they captured by defeating the Jaffna kings in battle as a separate unit. They permitted the people, as they agreed at the Nallur Convention, to be governed by their ancient customs and practices.

The Dutch and the British continued that practice till 1833. They also administered the territory that was under the Jaffna Kingdom in Tamil. Thus the territory that was under the Jaffna Kingdom during 1215- 1619 continued to be administered as a separate unit from 1619- 1833.

As pointed out in the last chapter the British East India Company captured the Dutch possessions in Sri Lanka in 1796. The East India Company which had been ruling the Madras Presidency since 1750 was directed by the British government to take over the Dutch possessions in Ceylon because Britain feared that they would fall into the hands of the French.

Britain monarchy was opposed to the French Revolution (1792- 1801) which resulted in the arrest of King Louis XVI of France in 1792 and his execution in January 1793. Great Britain formed a coalition with other monarchies and tried to crush the French Revolution that had become popular in Europe. That attempt failed.

Five years later, in 1798, Britain formed a second coalition and inflicted heavy losses on France. Napoleon Bonaparte who was in Egypt during that period, returned and seized control of the French government and launched a war against the neighbouring countries. He captured Holland and its king fled to Britain. Fearing that the French would take over the Dutch possessions in Sri Lanka and then attack India the British directed the East India Company to capture the Dutch possessions in Sri Lanka.

The British East India Company annexed Kotte and Jaffna to the Madras Presidency and made use of the Tamil tax collectors under its control to collect taxes in both territories. The East India Company took control of the pearl fishery and imposed several taxes including a tax on coconut trees. People of Kotte revolted and Britain took over the administration of the territories under the East India Company. It sent in 1798 Fredrick North and nine civil servants to take charge of the administration. The senior among the civil servants was Sir Hugh Cleghorn, a Scotchman. He was appointed Principal Chief Secretary and Governor’s Chief Advisor. He travelled throughout the territory under British control and was in charge of auctioning the rights for the pearl fishery. In a letter he sent to the British Government in June 1799 detailing the situation in Sri Lanka he wrote:

|

| Statue of Pandara Vanniyan |

Two different nations, from a very ancient period, have divided between them the possession of the Island: the Sinhalese inhabiting the interior in its southern and western parts from the river Wallouwe to Chilaw, and the Malabars (Tamils) who possess the northern and eastern districts. These two nations differ entirely in their religion, language and manners.

He advocated the takeover of the Sri Lankan possessions of the East India Company by the British Crown and recommended the continuance of the Portuguese and Dutch policy of administering the two territories the two nations occupied as separate units. Britain accepted that recommendation.

The British administered the two territories separately till 1833. Though they annexed Vanni to the Tamil territory, they administered the Kandyan territory separately, honouring the undertaking they gave to the Kandyan chiefs. Thus after the capture of the Kandyan Kingdom, there were three autonomous territories in Sri Lanka: Kotte, Kandy and Jaffna.

Pandara Vanniyan

One of the first decisions North took after the assumption of the office of Governor was to bring the entire country under British rule. Vanni and the Kandyan Kingdom were the only areas that remained outside their reign. The Portuguese and the Dutch had failed to subjugate those areas. North wanted to earn fame by capturing them. He started with Vanni.

The origin of the Vanni chieftaincy is not clearly established but researchers maintain that human settlements in Vanni commenced in the first century BC. The Konesar inscription and old folk songs say sixty Vanniyars accompanied the royal bride who came from Madurai in the first century BC to marry a king of Anuradhapura. Vanniyars would have been brought from North Arcot in Tamil Nadu. The Vanniyars were settled in Vanni.

Vanni came into the historical limelight around the beginning of the tenth century when the Pandyans invaded Sri Lanka and brought the northern province under their influence and control. Vanni’s importance increased during the period of the Chola invasion and Kalinga Magha gave importance to Vanni by making it one of his administrative divisions.

G.C. Mendis in his book Early History of Ceylon (page 70) says Vanniyars occupied the territory between the Kotte and Jaffna kingdoms and acknowledged the supremacy of one or the other and remained independent whenever possible. He adds that the Vanniyars tried to be independent after the Pandyan and Chola invasions. They were tributaries of the Jaffna kingdom after it became powerful.

Historically, the Vanni encompassed Mannar, Vavuniya, Trincomalee, Polonnaruwa, Batticaloa, Ampara and Puttalam hinterlands. But the Vanniyars in the Vanni region were powerful during the Portuguese and Dutch periods.

The Vanniyars belong to the warrior caste with heroic and martial skills. According to folklore, seven Vanni chieftains who fought unsuccessfully against the Dutch committed suicide to avoid capture. They are still revered at Natchimar temples in the Vanni and Jaffna.

With the capture of the Jaffna kingdom by the Portuguese in 1621 Vanni was under their nominal control and `Parangichetticulam` of the Vanni may have been the fort of the Portuguese.

The Dutch were only able to extract yearly tribute of 42 elephants from the Vanniyar chieftaincy. The conflict between the Dutch and Vanniyars came to an end when the Dutch defeated the Vanniyars in 1782.

The Portuguese and the Dutch found the Vanniyars a formidable foe. Lewi, a Dutch commander praised their fighting spirit and said he had never met such resistance anywhere else in the world. He especially praised the valour of Vannichi Kurivichhci Nachiyar, whom he said was taken prisoner and detained in Colombo fort.

Pandara Vanniyan, the last king of Vanni, was the most formidable of Vanni chieftains. He fought against the Dutch and the British. He formed an alliance with the Kandy monarchs in his bid to drive the British away. In his battle with the Dutch and the British, he adopted conventional and guerilla warfare.

In a surprise attack on the British garrison in Mullaitivu in 1803 Pandara Vanniyan’s forces, consisting mainly of Tamils of Vanni, overran the garrison and captured their cannons. The British forces under the command of Lt. von Drieberg withdrew to Mannar. Pandara Vanniyan’s forces overran the whole of Vanni and advanced up to Elephant Pass.

|

| The damaged tombstone of Pandara Vanniyan |

Vanniyan’s victory was short-lived. The British forces under the command of Drieberg attacked from three fronts- Jaffna, Mannar and Trincomalee- and defeated Pandara Vanniyan, captured and executed him on August 25, 1803. The British forces burnt all the houses which caused the people to seek refuge in the forest. Some of the people migrated to the Jaffna peninsula. The power of the Vanni Chiefs was thus finally and effectually extinguished.

Pandara Vanniyan became a folk hero and Pandara Vanniyan Nattu Koothu is popular among the Sri Lankan Tamil people even today. A tombstone was erected at the spot where he was defeated. It was damaged during the recent war following the Ceasefire Agreement.

Kandyan Wars

While consolidating the British rule by annexing Vanni Governor North turned his attention to the Kandyan Kingdom. His first attempt was to make it a British Protectorate through negotiations. He sent an emissary to Kandy on the pretext of congratulating Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe who succeeded his uncle Sri Rajathi Rajasinghe who died on July 26, 1798.

The mission failed because Vikrama Rajasinghe who had followed keenly the British intrigues and strategies that led to the conquest of South India was suspicious of the North’s intentions. He reasoned that it would be wiser to deal with the smaller countries like Portugal and Holland than with the British who had vast resources and the dream to conquer the world.

North who had, as indicated in the last chapter, held a secret meeting with Maha Adikaram Pilimatalawe in Sitawaka, sent two British detachments to capture the Kandyan kingdom. North took that decision on the strength that Pilimatalawe’s men would guide the British forces through the secret mountainous routes to Sengadagala where the king stayed. He also believed in the exaggerated stories Pilimatalawe told him about the king’s unpopularity.

The detachment that went from Colombo was led by Major-General Hay Macdowell and the one that marched from Trincomalee was commanded by Colonel Barbut. The British forces entered Sengadagala in February 1803 after a fierce battle. They found the city deserted. The British forces established a garrison and crowned Muttusami, the brother-in-law of the former ruler Sri Rajathi Rajasinghe, who had claimed the throne, as the new king of the Kandyan Kingdom. Then the forces moved to Kandy.

The British forces then encountered a series of difficulties. The Kandyans resorted to guerrilla warfare and inflicted severe damage on the British army. Locally recruited soldiers which included Malays defected to the Kandyan side. Disease also ravaged the British. The Kandyans counter-attacked in March 1803 and seized Senkadagala. Barbut was taken prisoner and executed, and the British garrison wiped out; only one man, Corporal George Barnsley survived to tell the tale. The British were unable to withstand the Kandyan attack retreated. The British forces were defeated on the banks of the flooding Mahaveli river, leaving only four survivors.

Kandyans did not stop with that. Their army, equipped with a handful of captured six-pound cannons, advanced through the mountain passes to Hanwella, a border town, but was routed by superior British firepower.

North maintained pressure on the Kandyan frontier the next year, 1804, with numerous attacks. He dispatched a force under Captain Arthur Johnson towards Senkadagala which was also defeated. The appointment of General Thomas Maitland as governor of Ceylon in 1805 brought a temporary end to the military pressure on the Kandyan Kingdom.

|

| Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe |

The second Kandyan war took place in 1815. During those ten years (1805 -1815) two different processes took place in the British-controlled areas and in the Kandyan Kingdom. In the British administered areas Governor Thomas Maitland consolidated British power and influence through a series of reforms and by bringing more Europeans into the country,

Maitland restructured the civil service and eliminated corruption. He created a Ceylonese High Court based on caste law. He enfranchised the Catholic population and withdrew the privileged position granted to the Dutch Reformed church. Maitland also undermined the Buddhist authority. He brought Europeans into the island by giving them large extents of land. Sir Robert Brownrigg who succeeded him in 1812 largely continued these policies.

Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe, on the other hand, created a situation that led to instability in Kandy. He executed Pilimatalawe and tortured and killed the members of his family which turned out to be very unpopular among the Kandyan nobles. He also antagonized the Mahanayakes through arbitrary requisitions of land and treasure. The British made use of this discontent to overthrow the king. The role played by John D’Oyly, a British civil servant, in the overthrow of the Nayakar monarchy was significant.

The events connected with the Second Kandyan war and the Kandyan Convention had been given in the last chapter.

The British honouring the undertaking they gave the Kandyan chiefs administrated the Kandyan areas as a separate unit. Thus in 1815 Sri Lanka was administered as three units: Kotte. Jaffna and Kandy. That continued till 1833. A change was made in that arrangement in 1833 as a consequence of the 1818 revolt.

The Kandyans revolted in 1818 because they realized that the British were in no way better than the Nayakar kings. Discontent with British activities soon boiled over into open rebellion in Uva and Wellassa. Hence the rebellion is usually referred to as the Uva Rebellion or Wellassa Rebellion. The revolt was Sri Lanka’s first struggle for Independence from British rule. It is also known as the “Great Rebellion of 1818”.

The Kandyans were greatly affected by the administrative policies of the British and were not used to being ruled by a king who lived far away in another continent. This created unrest among the local people and the aristocratic Chiefs in the Kandyan Kingdom. The rebellion was led by Wilbawe, an alias of Duraisamy, a Nayakar of Royal blood, and Keppetipola Disawe. Keppetipola was sent by the British to stop the uprising. Most of the Kandyan chiefs joined the rebellion.

The rebels captured Matale and Kandy before Keppetipola fell ill and was captured and beheaded by the British. His skull was abnormal – as it was wider than usual – and was sent to Britain for testing. It was returned to Sri Lanka after independence and now rests in the Kandyan Museum.

The rebellion failed due to a number of reasons. It was not well planned. The areas controlled by the Chiefs who helped the British provided easy routes to transport food and other necessities. Doraisami [Duraisamy], one of the leaders, did not have many followers.

The British suppressed the rebellion by arresting and executing the rebels through ‘Search and Destroy operations. Houses, property, livestock and even the salt in their possession were destroyed. The irrigation systems in Uva and Wellassa were also systematically destroyed.

Herbert White, a British Government Agent in Badulla minuted in the ‘Journal of Uva’:

“It is a pity that there is no evidence left behind to show the exact situation in Uva in terms of population or agriculture development after the rebellion. The new rulers are unable to come up to any conclusion on the exact situation of Uva before the rebellion as there is no trace of evidence left behind to come to such conclusions. If thousands died in the battle they were all fearless and clever fighters. If one considers the remaining population of 4/5 after the battle to be children, women and the aged, the havoc caused is unlimited. In short the people have lost their lives and all other valuable belongings. It is doubtful whether Uva has at least now recovered from the catastrophe.”

The British blamed Ehelepola for the revolt. He was arrested, taken to Colombo and exiled to Mauritius, where he died in 1829.

Unification of Sri Lanka

According to K.M. de Silva in The History of Ceylon, “Thus the year 1818 marks a real turning point in the history of Sri Lanka”. The British became the masters of the entire island. The whole of Sri Lanka had not been under a single ruler after the days of Parakramabahu I and Vijayabahi I. Though Kotte King Parakramabahi VI claimed control of the entire country his supremacy lasted for only 17 years when Sapumal Kumaraya ruled Jaffna.

Even Parakramabahu I and Vijayabahu I did not try to bring about the unification of the administration of the entire country. The British who wanted to prevent rebellions in the future started a process of unifying the administration of the country while abolishing or reducing the privileges of the nobles.

The two governors who succeeded Brownrigg who retired on February 1, 1820 – Edward Paget (February 1812 –November 1822) and Edward Barnes (January 1824- October 1831) continued Brownrigg’s policy of unification of the country. They adopted the following measures to achieve their objective:

- Unified the administration under British officials.

- Introduced the use of English for official purposes,

- Started English language schools,

- Opened up roads to the different regions and

- Introduced plantation agriculture.

All these measures taken together started the process of the unification of the country. Yet they administered Kotte, Jaffna and Kandy as separate units. To complete the process of unification Governor Barnes requested the British Colonial Office to send a Royal Commission to look into the administration of the three units.

The Unitary State

King George IV appointed in April 1829 a Royal Commission headed by Major W M G Colebrooke to examine “all laws, regulations and usages of the settlements in the island and into every other matter in any way connected with the administration of the civil government”. Colebrooke was followed by Charles Hay Cameron, who was commissioned to report on the judiciary.

The commissioners presented their recommendations in 1832, suggesting the creation of one government with one centralized, unitary form of administration under a governor in Colombo. The British did this without the consent of the people, and in doing so ended the hopes for a Tamil or a Kandyan nation as a distinct political entity, something that no conqueror had managed to do throughout the history of Sri Lanka.

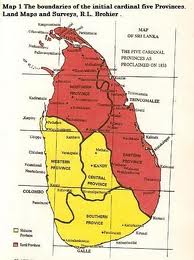

The Colebrooke commissioners also recommended that the Island should be divided into five provinces – Colombo, Kandy, Galle, Jaffna and Trincomalee. They further recommended the establishment of Executive and Legislative Councils.

This uniform administrative structure and the idea of a “united Ceylon” spelt doom for the Tamils’ distinctiveness which Sinhalese rulers had failed to achieve.

There were periods when Sinhalese kings ruled the whole of Sri Lanka. Under the monarchical system that prevailed during those times what they achieved was the supremacy of the entire country by making the other rulers their tributaries. They never imposed their administration in the territories they brought under their control.

A look at the definitions of the words monarchy, tributary and unitary state clearly indicates that Sri Lanka was never a unitary state. We have had monarchies and tributary states but never a unitary state. Whenever Jaffna was conquered by a Sinhalese king he never interfered with the local administration. Even in the case of Sapumal Kumaraya, he did not disturb the existing administration. In a unitary state that is not so. A unitary state is a sovereign state governed as one single unit in which the central government is supreme and any administrative divisions (subnational units) exercise only powers that the central government chooses to delegate.

The Colebrooke Commission by introducing the unitary form of government changed the political structure of Sri Lanka. C.G. Mendis has recognized this fact in his book Early History of Ceylon. He considers the Colebrooke reforms to be the dividing line between the past and present Sri Lanka.

Five Provinces

As noted above the Colebrooke commissioners recommended that the Island should be divided into five provinces – Colombo, Kandy, Galle, Jaffna and Trincomalee. The demarcation of the five provinces was done through the proclamation of September 30, 1833.

When the British East India Company took over the administration of the maritime territories from the Dutch it placed them under the Madras Presidency. When Sri Lanka was declared a Crown Colony in 1802 the government reverted to the system of administration adopted by the Dutch which closely resembled the native authority structures and divisions of earlier times.

The British officials divided the maritime areas into what they called collectorates, which were: Colombo, Kalutara, Galle, Matara, Negambo. Chilaw, Batticaloa, Trincomalee, Vanni, Jaffna and Mannar. Subsequently, the collectorates were abolished and the territory was divided into 13 provinces including those of Jaffna, Mullaitivu, Trincomalee, Batticaloa and Mannar.

Following the recommendation of the Colebrooke Commission, the 13 provinces were fused into five provinces through the proclamation issued by Governor Norton. In forming the five provinces British administrators took care to adhere to the existing political divisions.

According to the Proclamation the territories of the Northern and Eastern Provinces were demarcated thus:

The Northern Province shall consist of the country hitherto known as the Districts of Jaffna, Mannar, and the Wanny as the Dissawany of Nuwerekalawiya and as the Island of Delft;

The Eastern Province shall consist of the country hitherto known as the districts of Trincomalee and Batticaloa and as the Provinces of Talamkadewe and Bintenne.

The territorial limits mentioned in the Proclamation depict the areas under the control of the Tamil people in 1833. In the subsequent years the number of the provinces were raised to nine and the main suffers were the Tamils.

The sixth province called the North Western Province was created in 1845 by the annexation of territories from the Western and Central Provinces. In 1873 the North Central Province was constituted by bringing together Nuwarakakalaviya of the Northern Province, the seventh province, and Thambankaduwa of the Eastern Province and Demala Hatpattu of the North Western Province. The provinces of Uva and Sabragamuva were formed in 1886 and 1889 bringing the number of provinces to nine.

The Sinhala belief that the island of Sri Lanka belonged to them and the Tamil belief that they too have a similar claim was the basic cause of the Sinhala Tamil conflict. It was accentuated by the unitary state structure thrust on them by the British.

Next week; Emergence of Nationalisms

https://www.sangam.org/2010/09/Tamil_Struggle_6.php?uid=4060

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.