A Dravidian citadel: Here is a brief guide to understanding Tamil Nadu politics

Politics in Tamil Nadu is unique because of two factors: the influence of the Tamil film industry and the total dominance of ‘’Dravidian’’ parties.Aprameya Rao May 04, 2016 15:41:49 IST

The chaotic environment during elections — including all the rallying, speeches, and party promises associated with it — is at its fever pitch in Tamil Nadu, where elections are just like some religious carnival.

Politics in this state is unique because of two factors: the influence of the Tamil film industry and the total dominance of Dravidian parties. Here is a quick guide to Tamil Nadu politics, this state’s political history and its intricacies:

The Self-Respect movement

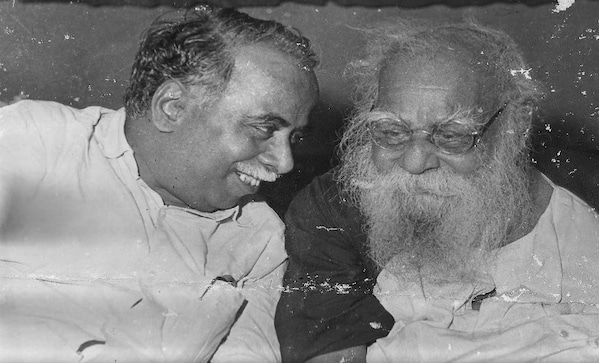

Self-Respect movement founder EV Ramasamy with DMK founder CN Annadurai. Wikimedia Commons

EV Ramasamy, fondly called Periyar, founded the Self-Respect movement in 1925 in the erstwhile Madras Presidency. It encouraged non-Brahmins – called Dravidians – to abandon the “superstitious” Vedic culture, revert to the ancient Dravidian civilization, and develop rationalist thoughts. Brahmins were scorned for introducing “alien practices” like the caste system, branded “North Indian outsiders”, demonised as“Aryan colonialists”, and in many cases, also attacked. Atheism was the cornerstone of the movement as Brahminical rituals were condemned. One outcome of it was the “self-respect marriages”, an alternative for marriages that were conducted without a Brahmin priest. The propagation of the Tamil language has been the biggest hallmark of the movement.

Pre-independence Dravidian politics

P Theagaraya Chetty (centre, in the front row), the founder of the Justice Party. Wikimedia Commons

The Justice Party is generally accepted as the predecessor of the DMK and AIADMK. Formed in 1916, it was mainly controlled by landowners and non-Brahmin upper castes. However, it shared its ideals with the Self-Respect movement. It introduced reservations in educational institutions and brought about religious reforms while in power between 1920 and 1937. Nevertheless, it lost its relevance after being identified as a non-Brahmin elite party, and finally merged with Periyar’s Dravidar Kazhagam in 1944. The social movement began taking a political turn in 1937 after the Congress government made Hindi a compulsory language. This was vehemently opposed by followers of Periyar, who termed it a “Brahmin-Bania ploy” to colonise the “Dravidians”. From then on, until 1962, it demanded an independent nation called “Dravida Nadu”. The demand never really found any takers and fizzled out.

Tamil Cinema and Dravidian politics

AIADMK founder and former CM MG Ramachandran with veteran actor Sivaji Ganesan. Wikimedia Commons

Cinema transformed Tamil politics, providing it with an excellent platform for propagating Dravidian ideals. Parasakthi, written by Karunanidhi and released in 1952, is now considered a major milestone for the movement. Such kind of movies explicitly or implicitly propagated ideals of social justice, rationalism and anti-Brahminism. Actors like MGR, SS Rajendran, Sivaji Ganesan and MR Radha were the early torch-bearers of the DMK in the industry. When MGR formed his own party, he used his movies to build his vote base. Kollywood and Tamil politics are so inseparable that when superstar Rajinikant urged voters to vote against Jayalalithaa in the 1996 elections, her party was routed. The fact that a former actress presently rules the state, and that actors like Vijayakanth have their own party, is a testimony to the influence of cinema in Tamil Nadu’s politics.

The rise of DMK

DMK patriarch M Karunanidhi. Reuters

The political plunge bore fruit in 1967, when the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, an offshoot of the Dravidar Kazhagam, swept the Assembly elections. CN Annadurai became the Chief Minister and remained in office until his death in February 1969. He was succeeded by M Karunanidhi – the incumbent president of the party. The first government legalised “self-respect marriage”, implemented pro-poor schemes like providing subsidised rice and promoted the Tamil language. The party won its second consecutive election in 1971. By then, however, inner-party rivalry and allegations of corruption weakened the ideological bearings. A year later, actor MGR left the party to form his own – All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam. This split the Dravidian movement into two and the rivalry between them continues till date.

The MGR era

AIADMK founder and former CM MG Ramachandran. Wikimedia Commons

The year 1977 was a landmark one in Indian politics as Marudhur Gopalan Ramachandran – popularly known by his acronym MGR – became the first film star-turned-Chief Minister of any Indian state. He remained the CM till his death in December 1987; winning three consecutive elections. The mid-day meal scheme – now almost in every state – has been the legacy of his government. However, his “populist” administration was also beset with allegations of rampant corruption and bureaucratic inefficiency, as the state economy crumbled under the burden of subsidy. He led AIADMK to share power at the Centre – a first for any Dravidian party – when Aravind Bala Pazhanoor and Satyavani Muthu were inducted into the short-lived Charan Singh government. His death split the party into two factions – one led by his wife Janaki Ramachandran and the other by Jayalalithaa who later prevailed.

The Jayalalithaa era

Tamil Nadu CM J Jayalalithaa. Reuters

Jayalalithaa joined AIADMK in 1982. She was appointed Propaganda Secretary and also nominated to the Rajya Sabha. After her mentor MGR’s death, she took over the party leadership and unified the party. In the wake of Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination in May 1991, AIADMK swept to power in the subsequent election. Marred by allegations of blatant corruption, she lost the 1996 elections.

Consequently, a judicial probe was launched, leading to her brief imprisonment. Nevertheless, her party made a comeback in the 2001 elections. Though her second term was less controversial, she lost the 2006 elections. AIADMK is currently in power after routing arch-rival DMK in the 2011 elections. It is also interesting to note that she became the first sitting CM to be disqualified after conviction in September 2014. After the Supreme Court overturned the conviction, she returned to head the government in May 2015.

Dravidian parties and the Union Government

DMK patriarch Karunanidhi with former PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee. Reuters

Dravidian movement distinguished itself with its rabidly anti-North and anti-Centre stance. However, with the passage of time, political motivations surpassed ideology and made both parties share power at the Centre. While AIADMK has been at the Centre only briefly – 1979 and 1998-1999, DMK has been a key component of various Union governments since 1989. Notably, it has been a part of every alliance in the past three decades – National Front, United Front, National Democratic Alliance (NDA) and the United Progressive Alliance (UPA). In the run-up to the 2004 general election, the DMK tied up with the Congress. The alliance swept all the 39 seats and helped the latter form the government at the Centre. A stand-alone AIADMK won all but two seats in the 2014 Lok Sabha polls – most number of seats for any Dravidian party ever.

Caste in Tamil Nadu politics

PMK leader Anbumani Ramadoss. Reuters

The Dravidian movement visualised a casteless society. However, political pursuits have encouraged both parties to build caste-based vote banks. Tamil Nadu politics is dominated by a few castes, mainly the Chettiars, Thevars, Nadars, Mudaliyars, Gounders and the Vanniyars. Except for the Chettiars – a forward caste, most of the other politically powerful castes are classified Backward Castes (BC). Both Dravidian parties pin their electoral hopes on BCs who constitute 68% of the population. While Thevars are generally considered a traditional AIADMK vote-bank, other caste vote-banks have straddled the political spectrum. There are few prominent caste-centric parties like the Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK), which represents the Vanniyars, and the Vidhuthalai Chirutigal Katchi (VCK) – a Dalit party. These parties, however, have only been at the periphery of state politics.

A virtual two-party system

A file photo of AIADMK supporters celebrating party victory. Reuters

Tamil Nadu is one bastion which the Congress has failed to breach since losing power in 1967. It has been relegated to playing second fiddle to either of the parties. The Bharatiya Janata Party is a virtual non-entity here while smaller Dravidian groups like the MDMK and DMDK have negligible impact on the electorate. Since 1989, neither Karunanidhi nor Jayalalithaa have won consecutive assembly elections. Both have alternately occupied the Chief Minister’s seat at St George Fort.

But whether 2016 sees a change in the trend is something to watch out for.

Updated Date: May 18, 2016 17:3

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.