Class, caste and the politics of destruction

August 10, 2020

UNP’s Defeat – I

By Jayantha Somasundaram

“… the liberal-cosmopolitan intelligentsia … supported … the UNP. Few, very few, designed to support the SJB.” Dr Dayan Jayatilleka The Election Result and the Intelligentsia (Colombo Telegraph August 7, 2020)

According to Karl Marx, history repeats itself, appearing the first time as tragedy and the second time as farce. This adage is very fitting when we look at last week’s Parliamentary election results, the political fate of the United National Party (UNP), and at events that occurred 30 years ago.

First the context: South Asia is a feudal society and is, therefore, subject to caste stratification and caste bigotry. And in Sri Lanka, too, caste consciousness and discrimination is pervasive. It determines political alliances, political fortunes and political history. The Sinhala Govigama elite did not see the other major castes, even after they had acquired wealth and education, as mere inferiors. They viewed them as lacking legitimacy because, as Professor K.M. De Silva explains in The History of Sri Lanka, “recent immigrants, from South India, and their absorption into the caste structure of the littoral, saw the emergence of three new Sinhala caste groups – the Salagama, the Durava and the Karava. They came in successive waves into the eighteenth century.”

When an elected-Ceylonese seat was introduced in the Legislative Council, in 1911, the Govigama leadership united behind the Tamil Vellalar Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan in order to defeat his opponent, the Karawe Sir Marcus Fernando, whose candidature was proposed by Sir James Peiris. This led Governor Sir Hugh Clifford to say that the election “was fought purely on caste lines … caste prejudice providing a stronger passion than racial bias.”

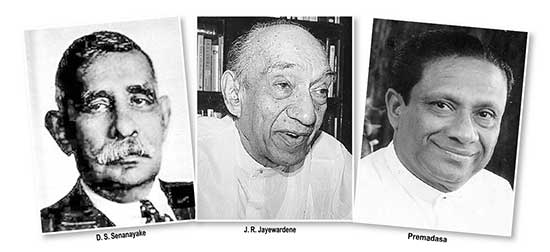

The UNP, founded in 1946, reflected this mindset. “D.S. Senanayake had entered independence with a basically Sinhala-Govigama and Tamil-Vellalar administration” observed Janice Jiggins in Caste and Family in the Politics of the Sinhalese. Inspector Malcolm Jayasekera, who was attached to Prime Minister D. S. Senanayake’s security detail, recalled that when ministers travelled to the provinces, Sir Ukwatte Jayasundera, the General Secretary of the UNP, would, at their Rest House stops, join the security detail for lunch, because, as a member of the Navandanna caste, he didn’t feel welcome at the table of his ministerial colleagues.

When Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike was assassinated, in 1959, the Leader of the House was C.P. De Silva. Professor A. J. Wilson records, “Dr N.M. Perera told me that the Governor-General, Sir Oliver Goonetilleke, was going through a ‘Gethsemane’ in his presence, asking, ‘How can I appoint a Salagama man’ (as Prime Minister)?”

Caste discontent became obvious during the April 1971 uprising when it was found that the combatants of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) were from depressed caste groups, like the Batgam and Vahumpura. Janice Jiggins notes that “Many in the armed services took the view that the fighting was an expression of anti-Govigama resentment and, in certain areas, went into low caste villages and arrested all the youth, regardless of participation.”

UNP’s 1970 Defeat

The shattering electoral defeat of the UNP, in 1970, compelled J. R. Jayewardene to depend on extra-parliamentary agitation to regain power, and street-wise activists, like R. Premadasa, with a base among Colombo’s underclass, and Cyril Matthew, the trade union boss. By the time the party took office, in 1977, Premadasa had become one of the contenders for leadership. But Premadasa belonged to a depressed caste.

“Previous leaders had come from the landowning Goyigama caste whose well-off members had quickly got onside with the British colonial rulers, sent their sons to elite British universities and learnt to play cricket and parliamentary politics …. Premadasa was Sri Lanka’s first leader to come from the lower orders. He had scant formal education.” (Far Eastern Economic Review 13/5/93) The prevailing political leadership, “the UNP’s J. R. Jayewardene and the SLFP’s Sirima Bandaranaike both belonged to the same Anglicised elite in Colombo.” (Asiaweek 12/5/93)

Since Jayewardene could only serve two terms, Premadasa was patient, confident that he would, in due course, become President. “Mr Premadasa was always searching for outside allies. He was forced to do so because of opposition to him, within the party. This opposition was based on class and caste factors… (and) was one of the factors which made Mr Premadasa try so hard to form an understanding with the JVP and the LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam).”(Sunday Leader 5/1/93)

However, Premadasa soon realised that the Govigama establishment, in the UNP, was grooming Upali Wijewardene to succeed Jayewardene. Married to Mrs Bandaranaike’s niece and a kinsman of Jayewardene, educated at Royal College and Cambridge University, successful businessman with an international empire, Wijewardene was the perfect successor. “His attempts to get into politics, through JR, was thwarted by Premadasa who felt Upali would be a threat,” wrote former The Island editor Vijitha Yapa, while Upatissa Hulugalle reminds us that “Premadasa cursed Upali in Parliament a few days before he disappeared.” (The Island 30/1/01). Upali Wijewardene was killed in a mysterious plane crash in 1982.

“In early 1990, when Vijitha Yapa was Sunday Times editor, a columnist published some cabinet news that Premadasa was angry about. At a function, at Gangaramaya Temple Keleniya, Premadasa told (Upali’s cousin) Ranjith Wijewardene (the owner of the Sunday Times) in a small gathering: “I want to advise you, do not let those who destroyed Upali destroy you.” (Colombo Telegraph 4/4/14)

Upali Wijewardene

In the Constitution, that he crafted in 1978, President Jayewardene was careful not to provide for a vice president, who would explicitly be regarded as his successor. So Premadasa had to be content with the inconsequential office of Prime Minister. “As Prime Minister, he had no powers,” said Premadasa’s daughter. “Despite his being deputy leader of the party and Prime Minister, he was not nominated for the presidency until the last moment. Both Lalith and Gamini were aspiring for the ticket.” (Sunday Island 4/1/97)

1988 Election

“Some Govigama politicians opposed the appointment of Premadasa, as deputy leader rather than Athulathmudali or Dissanayake, because it made him Jayewardene’s presumptive successor.” Though appointed Prime Minister, in 1978, when Jayewardene became executive President, the UNP leadership did not consider Premadasa as a prospective successor to Jayewardene. Instead “the leading contenders were Upali Wijewardene, Lalith Athulathmudali and Gamini Dissanayake. Wijewardene was a cousin of Jayawardene… and was, in 1982, considered a likely successor to Jayawardene.

To the very end of Jayewardene’s administration, Premadasa had no assurance that he would be the UNP’s candidate at the 1988 Presidential Election. “Nearly all those in the UNP hierarchy, who advocated a third term for President Jayewardene, were killed, ostensibly by the JVP,” notes Rajan Hoole in The Linkages of State Terror (UTHR). In a sense, it was the JVP that won him his candidature, they were at the height of their anti-Indo-Lanka Accord and anti-Indian campaign. The only way the UNP could win the presidential election was by putting up a credible nationalist. For example, a champion of the Indo, Sri Lanka Accord, Gamini Dissanayake was on a poor wicket. Premadasa finally became President, on 2 January 1989, of a Sri Lanka “riddled with caste distinction and snobbery… Premadasa remained an outsider until he died.” (Asiaweek 12/5/93)

Premadasa’s choice for Prime Minister would have been his loyal lieutenant Sirisena Cooray, but he could not ignore the fact that Lalith Athulahmudali came out the better of the two, in Colombo, at the 1989 Parliamentary Election. Rather than give Athulathmudali the position, with its implied deputy status, he invented an annually rotating premiership, assuring each aspirant a turn, and then appointed D.B. Wijetunga who was never a contender for office. Premadasa, thereafter, forgot about the ‘rotating premiership.’

On the anniversary of his installation as President, Premadasa “would receive a blessing from priests at the Temple of the Sacred Tooth, in Kandy, and then present himself to the public from a chamber where the ancient rulers of the Kandyan Kingdom were crowned. The upper-caste clergy, at Kandy, may have gritted their teeth at presumption by a person who traditionally would not have been allowed near their most holy places.” (Asiaweek 12/5/93)

“The dominant Siam Nikaya was once exclusively confined to the Govigama caste and remains overwhelmingly Govigama. The Karava, Salagama and Durava castes obtained ordination, in Myanmar, setting up the Amarapura Nikaya,” explains Punya Perera in “Caste and Exclusion in Sinhala Buddhism” (Colombo Telegraph 7/3/13)

(To be continued)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.