Where are the sisters of Telugu?

Most comparative linguists place Proto-Dravidian around 4500–3500 BCE.

This is a conservative consensus based on internal linguistic reconstruction, shared agricultural vocabulary across all Dravidian languages, and correlations with early Neolithic dispersals.

Two homeland models dominate the debate: the Central/South-Central Indian homeland (Lower Godavari–Krishna–Deccan corridor), which is currently the mainstream academic position, and the Elamo-Dravidian hypothesis, which links Dravidian to ancient Elam (southwestern Iran) and suggests a deeper, pre-4000 BCE ancestor—attractive but not conclusively proven.

Either way, Proto-Dravidian is extremely ancient, comparable in time depth to Proto-Indo-European.

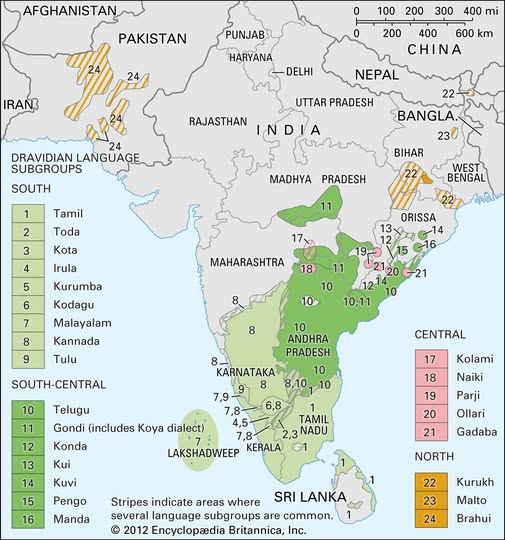

Around 3500–3000 BCE, Proto-Dravidian underwent its first major split, creating the South Dravidian, South-Central Dravidian, Central Dravidian, and North Dravidian branches.

This early divergence already introduced large genetic distances.

From Proto-South Dravidian (c. 3000–2500 BCE) emerged Tamil, Malayalam, Kannada, Tulu, and Kodava, forming the closest genetic cluster.

A crucial but often missed stage is Proto-Tamil–Kannada (c. 2500–2000 BCE), where Kannada branched off earlier.

Proto-Tamil (c. 2000–1500 BCE) later split into Tamil and Malayalam. This explains their exceptionally high mutual intelligibility and near-identical core grammar.

Geography shaped how different these languages feel.

The Western Ghats isolated Kerala, preserving older Dravidian forms and enabling a Sanskrit-heavy contact ecology that shaped Proto-Malayalam.

The Deccan plateau supported large speech communities that encouraged innovation and standardisation in Kannada and Telugu

The Krishna–Godavari river basins enabled Telugu’s expansion and early literary crystallisation.

Telugu belongs to the South-Central Dravidian.

Its close sisters are Gondi, Konda, Kui, Kuvi, Pengo, Manda, and Koya. They are languages genetically closer to Telugu than Tamil or Kannada ever were.

They are invisible because they lacked courts, scripts, and early literary traditions. They were later labelled “tribal” and faced assimilation into the Telugu, Odia, or Marathi languages.

Central Dravidian languages (Kolami, Naiki, Parji, Ollari, Dravidian Gadaba) occupy central-eastern India. They are grammatically conservative, minimally Sanskritised, and politically silent—true “living fossils” of Dravidian grammar.

North Dravidian, the smallest and most endangered branch, includes Kurukh (Oraon), Malto, and Brahui

They show that Dravidian once had a far wider prehistoric spread.

Brahui, spoken today in Balochistan amid Indo-Iranian languages, is to Dravidian what Tocharian was to Indo-European. It is an isolated survivor preserving unmistakable Dravidian structure, pointing either to an ancient northwestern Dravidian presence or migrations.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.